NEI Program for People with Disabilities Marks 10 Years

Photo: Bill Branson

Andrew Butler may be one of the hardest working people at NIH. He has to be, because he works at the Bldg. 49 Central Animal Facility on campus—home to the many rodents and other laboratory animals that are a vital part of NIH research. Butler’s daily shift in the cage wash and facility support area starts at 7 a.m. each day, but he arrives promptly at 6:15. Even after Winter Storm Jonas tore through the East Coast on Jan. 22 and snarled the NIH area for most of the following week, he reported to work on time every day except for that Monday, when his supervisors advised that he stay home.

Butler happens to be one of several workers with intellectual disabilities at the Bldg. 49 facility, which serves labs at several institutes and centers and is managed by NEI’s veterinary research and resources section.

Butler, who has autism, graduated from Seneca Valley High School in Germantown, Md., in 2006 at age 21. The high school helped connect Butler to job training and to his job coach Vicky Geiger of Rehabilitation Opportunities, Inc. When Butler graduated, she found him a volunteer mailroom position at Shady Grove Medical Center and later helped bring him to NIH and the Bldg. 49 facility. She is still working with Butler and his parents 8 years later.

Photo: Bill Branson

Butler is quiet and not one to sing his own praises, but Geiger says he is “very proficient” in his work. His parents, Charles and Cathy Butler, describe him as happy and an inspiration to his friends.

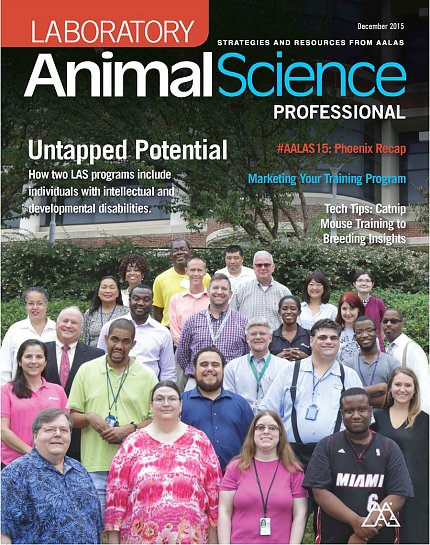

The NEI-led animal facility established a program for employing people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) 10 years ago and now employs 5 people with IDD including Butler. In December 2015, the facility’s management team published an article about the program in Laboratory Animal Science Professional, the magazine of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science.

Their goal? “We want to get the word out that people with IDD continue to be an underutilized resource who can markedly improve your workforce,” said Dr. Robert Weichbrod, chief of animal program administration at NEI. He is senior author of the paper, along with Dr. James Raber, animal program director for NEI and NIMH.

Skilled and Dedicated

In their article, the authors point out that animal care and use programs face many staffing challenges. Entry-level jobs at these facilities tend to offer low pay. These jobs can also be physically demanding and stressful, with the potential for daily operations to grind to a halt if someone is absent or not keeping up with work flow. Employees also face several occupational risks, such as potential injuries from heavy machinery, animal bites and scratches and possible allergic reactions to fur, dander and animal waste. There are many procedures to ensure employee safety—and animal welfare—that need to be followed precisely.

Meanwhile, people with IDD are often overlooked as potential employees. An analysis by the White House Council of Economic Advisors found that only one-third of working-age Americans with disabilities were employed from 2010-2012, compared to more than two-thirds of Americans without disabilities during the same period.

Photo: Bill Branson

Weichbrod and his co-authors say that the key to changing that statistic is to look past a person’s disabilities to his or her unique skills, attitudes and life experiences. Their team members with IDD “have a remarkable commitment to the job that is rarely seen in the workforce,” Weichbrod said. “They come in early, or when they’re not feeling well, or when there’s inclement weather. They are extremely proud of the work they do.”

During Winter Storm Jonas, Katherine Hall spent 3 nights in Bldg. 49 sleeping on a cot. Hall, who has Asperger syndrome, is a licensed veterinary technician at the facility and has worked there since May 2015. (She is also a member of the board of directors for the Autism Society of Northern Virginia.) She takes care of the facility’s mice and rats, which includes feeding them, changing cages and doing health checks to report illnesses, births or other issues.

Prior to joining the animal facility staff, Hall worked for a veterinary hospital in Alexandria. The hospital was “a small space with a lot of chaos going on all the time,” she said. “Here, it’s more working with animals than working with customer service. I’ve always loved animals and I kind of understand them better than people. I really enjoy it here.”

Dream Job

The NEI program began thanks to a chance encounter at a Special Olympics event. Weichbrod, whose late daughter Gretchen was a Special Olympics athlete, has been an ardent participant in the organization’s events and fundraisers. In December 2005, he was at a Special Olympics holiday party when an Olympian named Joe Wu struck up a conversation with him and asked about job opportunities.

As it happened, the NEI facility had a need for additional staff. So Wu was brought in as a volunteer to work on the loading dock. After a trial period, he became a paid contractor and advanced to other facility support positions.

“It’s been my dream job,”

Wu said.

Wu’s experience became a model for taking on other staff with IDD, with community resource providers helping fulfill recruitment. These are organizations that receive state and local funds to support employment for people with disabilities, in part through job coaches like Geiger. The coaches know the abilities of the candidate and learn about the needs of the workplace; they help to manage expectations, performance and satisfaction on both sides. There are regular check-ins involving family members, the job coach, management and human resources, including an annual review required by Maryland law.

Challenges and Solutions

What advice do Weichbrod and his colleagues offer for other workplaces interested in recruiting people with IDD? One step is to get involved with community groups such as Special Olympics and Best Buddies, which can help employers make connections, advertise job opportunities and share success stories.

Photo: Bill Branson

The authors also advise seeking help from non-profit organizations that aim to improve employment for people with disabilities. For example, the organization Seeking Equality, Empowerment and Community for People with Developmental Disabilities and the Ivymount School in Rockville have partnered to sponsor and manage a 1-year internship program at NIH. It’s called Project SEARCH and is designed for young adults with IDD who are high school seniors or recent graduates. While most of the interns work at the Clinical Center, some have worked in NIH’s animal care and use programs, including the Bldg. 49 facility.

For federal employers, the Department of Labor has an online toolkit that offers training and best practices for recruiting and retaining people with disabilities. It followed a 2010 Executive Order by President Obama directing the federal government to become a model employer of workers with disabilities.

The NEI program’s managers are candid about the many challenges of employing people with IDD, including the time and resources that must be invested for special training. They say these costs are balanced by lower employee turnover and recruitment costs. They also advise allowing more time for people with IDD to adapt if there is a need to change job responsibilities. People with IDD may also have more difficulty adjusting to new staff and saying goodbye to coworkers who leave. But that can be a source of strength, too.

“Our support for each other goes beyond the workplace,” said Alexine Chevalier with Priority One Services, which handles human resources for the program’s contract staff. “There is a dedication from management and families that makes the program very close-knit.”