‘Star of Gladness’

For Native Hawaiians, Canoe Instills Pride, Healing

Photo: Bill Branson

What brought members of a Hawaiian canoe crew to NIH? It’s a story of cultural revival and communal healing. It’s a story of treacherous journeys into an unforgiving ocean to connect with their Native Hawaiian heritage and rekindle the spirit and pride of an endangered population.

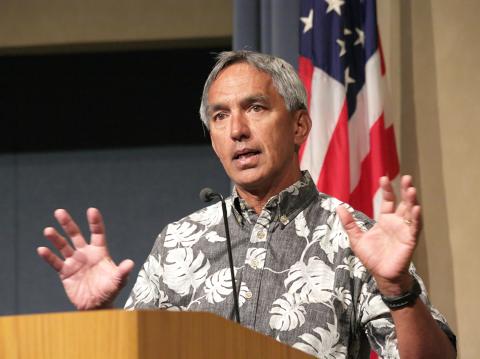

Nainoa Thompson, president of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, gave an impassioned talk to an overflowing crowd in Lister Hill Auditorium recently. He described the hope and tragedy of his voyages aboard the canoe Hōkūle‘a, meaning Star of Gladness, which coincided with the cultural renaissance of Native Hawaiians in the 1970s.

They’d been second-class citizens in their own land for decades, their language and culture suppressed. And they were dying out. When Capt. Cook sailed to Hawaii 250 years ago, there were up to 1 million Native Hawaiians, descended from the original Polynesian settlers. But the 1922 Census recorded only 22,000, many having succumbed to malaria, smallpox, influenza and other diseases.

Photo: Bill Branson

“We know what extinction smells like. We know when we’re going down the uncomfortable road of loss,” said Thompson.

But with improved medical care, the tide began to turn and the population continued to grow throughout the 20th century. The 1970s saw a flourishing of native art, music and dance. By 1980, Hawaiian language was again taught in the state’s schools.

“Renaissance was beyond blood; it was about values and courage,” said Thompson. It was a time of rebirth and Hōkūle‘a was an integral part of that story.

For centuries, voyaging canoes had traveled around the Polynesian islands. But these double-hulled canoes that brought the first Hawaiians to Polynesia disappeared. In 1968, artist Herb Kāne designed a replica of the canoe his ancestors had sailed and by 1975, Hōkūle‘a was built, the first of its kind in 600 years. But the voyaging canoe had no instruments so they needed a navigator, recounted Thompson. They found a renowned one in Micronesia: Mau Piailug, a traditional navigator who used the stars, sun, moon and ocean swells as his compass.

Photo: Bill Branson

Hōkūle‘a set sail on her maiden voyage in May 1976 with a full crew, some scientists and several National Geographic photographers eager to document the journey. A month after setting sail, they reached Tahiti and an estimated 17,000 Tahitians excitedly swarmed the pier to greet them.

“It was the first time I felt whole,” said Thompson. “My gravity to the ocean and my love for my culture to instinctually know as a young man, you’re part of something very special…that being in the wake of your ancestors was a way you felt healed.”

In 1978, the crew set sail again from Oahu but they were ill-prepared and soon encountered rough currents and gale-force winds. The 62-foot canoe capsized.

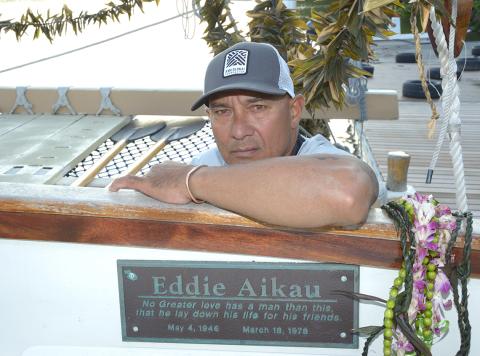

Photo: Bill Branson

One brave crew member, Eddie Aikau—an accomplished surfer—without hesitation grabbed his surfboard, as a crewmember tied a bag of oranges and a dagger onto his waist, and set out to find help. Salt kicked up from the gale creating a fog and Aikau’s eyesight was poor, but he went anyway.

“If you want to know Renaissance, for his people this man paddled to an island he couldn’t even see,” Thompson tearfully recounted. The Coast Guard came and rescued the crew, but Aikau was lost at sea.

The crew felt paralyzed after Aikau’s death, said Thompson, but they knew they had to sail again. “If Hōkūle‘a was the flame and the light of hope, if it was like the flashlight in the darkness of the depression, then if its legacy would only be defined by its tragedy, how many generations would be set back?”

For the third voyage, they trained well and Thompson became a student navigator under Piailug. They set sail in 1980 and reached Tahiti in 31 days. The canoe continued on successive voyages, sailing more than 140,000 nautical miles across the Pacific.

Photo: Bill Branson

Native Hawaiians are still navigating their way toward improved health and education. The 2000 Census recorded nearly 300,000 native Hawaiians; it is projected there will be more than 1 million by the mid-21st century. In the 1970s, said Thompson, there were only 11 Hawaiian doctors. Today, there are more than 300. “That’s an indication of health.”

Education is also changing. Immersion and charter schools are helping preserve Hawaiian language and culture. The University of Hawaii is teaching, alongside science and technology, indigenous know-ledge and sustainability.

Several original crew members were in the NIH audience that day, as was Alaska Lt. Gov. Byron Mallott who, in 1990, gave Thompson’s group Alaskan spruce from native villages to build the hull of a new voyaging canoe called Hawai‘iloa. “What Byron did was connect us,” said Thompson, “to find out the story is the same across the planet for all native people.”

Photo: Bill Branson

For Native Hawaiians, the cultural revival continues and the voyaging canoe is an important part of an ongoing renaissance.

“Renaissance was a time when there were those pioneers that would stand up for justice,” said Thompson, “take the ultimate risk for what they believed in, those who were centered and navigated by the core values, even if they stood by themselves, even if they paddled by themselves, even though they went to a place they couldn’t see. Renaissance, essentially in the end, meant knowing who you are, where you come from and what you believe in. Renaissance, in the end, is all about love and compassion and care for the things that mean the most.”