Block the ‘Passenger’

Beware the Intruder Hijacking Your Meetings

Photo: Ernie Branson

Ever wonder why so many meetings are so unproductive? Chances are good an uninvited guest has been riding shotgun. Turns out this unseen hitchhiker loves to sabotage your well-organized, well-intentioned workplace gatherings.

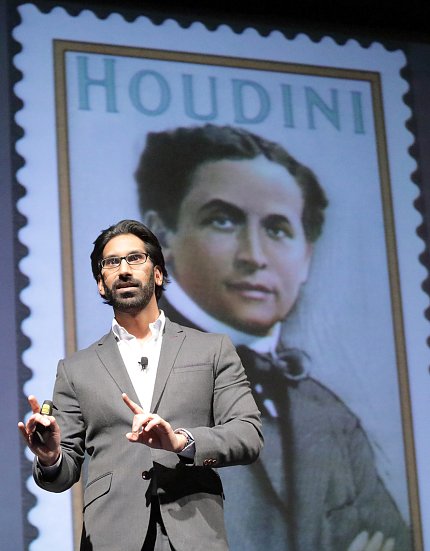

At a recent Deputy Director for Management seminar, author and business advisor Al Pittampalli, who has studied meetings for the past decade, introduced a Masur Auditorium audience to this invisible, yet powerful saboteur he calls “the passenger.”

Surveys estimate that anywhere from 25 percent to 50 percent of all meetings are unproductive, Pittampalli said. People report they feel that as much as half the time they spend in meetings is wasted. By a show of hands, NIH audience members nearly unanimously confirmed—perhaps humorously, perhaps not so much—that they’d attended at least one meeting that had made them reconsider their life’s purpose.

“Nothing can ever take the place of human beings getting in a room together to talk things out,” Pittampalli acknowledged. “Meetings are at the heart of how we communicate, how we collaborate, how we decide on the most important issues facing the organization. If that’s weak, then it’s hard to fulfill the mission of the organization. I’m here to tell you the meeting is weak.”

Pittampalli was an IT consultant for Fortune 500 companies around the country when meeting malaise first struck him. He set out to find treatments, if not a cure. For the first few years, he admitted, he had little success. Fine-tuning the meetings wasn’t working. He had to dig deeper.

“I don’t really care about meetings,” he confessed. “What I’m fascinated by is the organization. The promise of an organization is that lots of people working together in concert can do way more than any individual [could]…The meeting is just the tool that allows that to happen.”

Pittampalli said most everyone agrees on the requirements for a good meeting—a well-thought-out agenda, designated time limit, clear purpose, that a gathering is necessary in the first place. However, hardly anyone believes that having all these elements guarantees an effective session.

The issue “is not a knowledge gap,” Pittampalli explained. “It’s not that we don’t know what to do. It’s that we don’t do what we know.”

But, why don’t we? What’s stopping us?

Imagine you’re on a cross-country road trip, Pittampalli said. The destination is your organization’s mission, the ultimate goal. Meetings are the stops you make en route, for fuel, comfort breaks and rest.

“Unbeknownst to you,” he said, “an invisible passenger is in the car with you, causing the unproductive pit stops.” This specter embodies “psychological forces that operate within the human mind.”

Also known as “procrastination, “distraction” and “weakness of will,” these forces, Pittampalli said, lurk like a ghost at your meeting.

For the passenger, immediate gratification is top priority. “The passenger is all about getting what it can right now…has no interest in pursuing more speculative goals that pay off in the long term,” Pittampalli pointed out.

The passenger is also “a master in the art of deception,” he explained.

Photo: Ernie Branson

Consider two ways we are diverted from accomplishing our goals: “not-work” and “make-work.” Not-work includes all sorts of “pleasurable distractions,” like playing games on your portable device. But it’s also accompanied by guilt. “Guilt motivates us to get back to work,” Pittampalli said.

Make-work, however, is more diabolical. It resembles actual work, but can include seemingly harmless activities such as web-surfing, a delaying tactic that deadline-besieged writers often dub “research.” Meetings, Pittampalli contended, are a kind of make-work.

“They look like work,” he said, but so often they are not really moving toward the goal. Brainstorming sessions, status meetings, topic debates—all become “circular conversations or intellectual hamster wheels.” In these gatherings, Pittampalli said, the passenger “pulls a Houdini. He makes the decision disappear.”

So how can we dump the passenger? Three key questions can rescue your meetings, Pittampalli said.

First, what decisions need to be made? “Virtually every meeting is a decision-making meeting,” he stressed. Avoid using the four danger words: review, discuss, update and plan. While they sound good, they can easily hide procrastination and distraction. They can actually be obstacles to decision-making.

“The passenger abhors decisions,” Pittampalli said. “Decisions are evil to the passenger, because they cause pain in the short term and they don’t provide gain until the long term.”

Next, who is the decision owner? Hint: it’s not “consensus.” The passenger likes to undermine your meeting by obscuring responsibility for any decision. If you wait to get a consensus, your meeting may never end and may never be productive, Pittampalli explained. The decision owner makes sure the meeting ends with a result.

“If the passenger can prevent us from having a single point of accountability, it can turn our meetings into make-work,” he said.

Finally, does this meeting contribute significantly to our major goals? Identify just a few major goals, Pittampalli advised, and use those as your organization’s compass. Don’t call a meeting just for the sake of sharing information, for example. These days there are many other ways to communicate instead of meeting.

“We have to be more committed to achieving our goals than the passenger is to sabotaging them,” he concluded.

Audience members asked several questions: What can we do when no one follows through on decisions that were made? How do I tell the boss that meetings are not effective?

Pittampalli said everyone in the meeting shares responsibility for making it successful. Employees can help block passenger diversion by asking: What actions need to be taken? Who will take them and when?

“The reason this problem is so difficult to fix is that it’s cultural,” Pittampalli acknowledged. “We need a culture where people can ask these questions of each other…Culture change is tough, but it starts with [seminars] like this, where people are willing to get a little out of their comfort zone.”