Beetle Mania

Insect-Borne Pathogens Threaten Crops

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Wondering why the carefully tended vegetables in your garden have started to look rather lifeless? You’re not necessarily losing your green thumb. The culprit might be a pathogen, transmitted by a beetle or other invasive critter, which can rapidly invade susceptible plants.

These days, the headlines are dominated by such mosquito-borne viruses as Zika and dengue, but there are also numerous bacterial pathogens that affect hundreds of plant varieties.

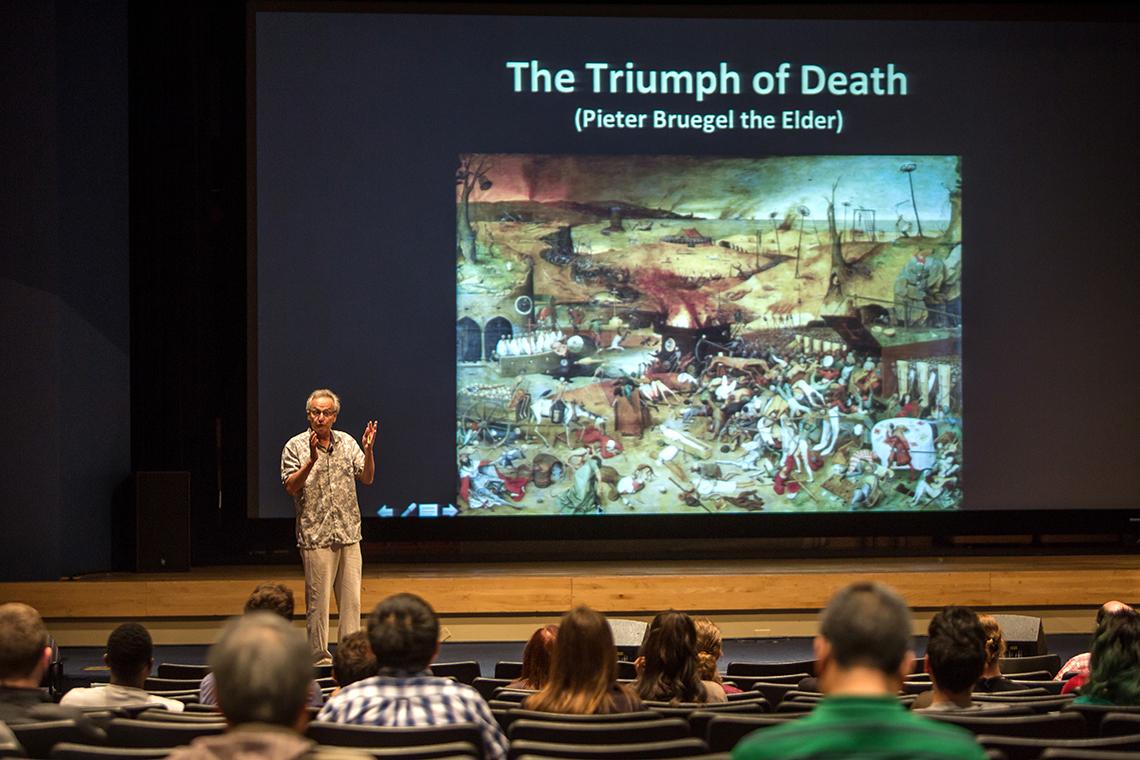

One common insect-borne disease, bacterial wilt of cucurbits, is of particular interest to Dr. Roberto Kolter, a microbiology professor at Harvard Medical School, who delivered the Wednesday Afternoon Lecture recently. His lab is studying the evolution of this fatal plant disease, an annual epidemic in the northeastern United States. It’s a story of old world meets new world, microbiology and anthropology, food security and health.

Cucurbit crops—certain types of cucumbers, melons, squash, pumpkins and gourds—are vulnerable to a bacterium called Erwinia tracheiphila, spread by the common cucumber striped beetle.

Unfortunately for the cucurbit, the beetle co-evolved with this plant and it’s the only kind this beetle will eat. E. tracheiphila evolved more recently and found a ripe population to invade. Once infected, the plant starts to wilt and its fate is sealed; the cucurbits die within a couple of weeks.

“Once you have a pest and a pathogen...the population has to be susceptible and it needs to be high density so the transmission can be fast and effective before [the host] population is decimated,” said Kolter. “If the populations are genetically lacking in diversity, that really renders a much greater chance for that invasion to be remarkably successful.”

Pathogens tend to attack dense, homogeneous populations, said Kolter, and are responsible for the loss of more than 10 percent of wheat, corn and other U.S. crops. This threat to food security is a consequence, he said, of being so dependent on crops that lack diversity.

One such pathogen that hit Europe hard caused the infamous Irish potato famine in the 19th century. Millions of people died when Phytophthora infestans caused potato blight. This pathogen migrated and invaded mainland Europe multiple times.

Land plants have existed for 400 million years, said Kolter, who has studied the evolutionary origins of plant pathogens. Some 175 million years ago, squash plants started to evolve separately, each with its own collection of herbivores, he said. Humans began to cultivate and domesticate these plants 10,000 years ago. Old world met new world about 500 years ago when European settlers brought cucumbers and melons to the eastern United States.

“Now you have a pathogen in the making, perhaps, that finds a host that had never been there that is now being planted in high densities and continues to do so for the next 500 years,” Kolter said. “We think this probably is the time that dates the E. tracheiphila evolution.”

In the case of the cucurbit, its bitter taste and spiny leaves ward off predators. But its defensive compounds also are toxic, deadly to many animals, which led to co-evolution with certain specialized beetles. E. tracheiphila, inflicted by beetles, grows in the xylem and clogs the plant’s vascular system, blocking water and nutrients from reaching the shoots.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Kolter scientifically explained the process. “Beetles eat and poop at the same time. When the beetle feeds on the plant and poops into the wounds, the plant gets infected...Our agricultural landscapes are conducive to the success of this pathogen even though it has evolved, as of now, only inefficient ways of transmitting the disease.”

Interestingly, Kolter’s team confirmed what they witnessed in the field. The beetle prefers eating infected, already wilting leaves but healthy flowers. The wilted leaves give off volatiles that attract the beetle, he said, and the healthy flowers produce another set of attractants.

In another curious observation, the pathogen attacked both the new world Cucurbita pepo—squash, pumpkin, gourds, zucchini—and the old world Cucumis sativus (cucumber) plants but was more virulent in cucumbers than the native squash. Kolter’s lab is currently doing genomic testing to learn more but has confirmed that E. tracheiphila is temperature dependent, which explains its geographic restriction to the Northeast.

In a field with scarce funding, Dr. Lori Shapiro in Kolter’s lab has turned to citizen science. Working with Prof. Rob Dunn of North Carolina State University, Shapiro is recruiting students to plant cucurbits in school gardens with the goal of involving 5,000 schools. Their program is slated to begin this growing season at 500 schools.

“This will be a great resource, not only for sequencing the strains,” he said, “but also for following the bio-geography of the beetle and exposing children to real research.”

To help control bacterial wilt of cucurbits, Kolter advises planting diverse vegetable varieties in our gardens. Hybridization is a good defense. “Maybe your squashes will be a bit smaller,” he said, “but that’s okay. Maybe they’ll have more flavor.”