Star-Like Cells May Help Brain Tune Breathing Rhythms

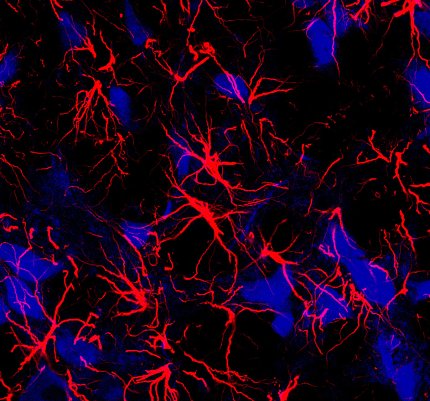

Photo: Jeffrey C. Smith lab, NINDS

Traditionally, scientists thought that star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes were steady, quiet supporters of their talkative, wire-like neighbors, called neurons. Now, an NIH study suggests that astrocytes may also have their say. It showed that silencing astrocytes in the brain’s breathing center caused rats to breathe at a lower rate and tire out on a treadmill earlier than normal. These were just two examples of changes in breathing caused by manipulating the way astrocytes communicate with neighboring cells.

“For decades we thought that breathing was exclusively controlled by neurons in the brain,” said Dr. Jeffrey C. Smith, NINDS senior investigator and a senior author of the study published in Nature Communications. “Our results suggest that astrocytes actively help control the rhythm of breathing. These results add to the growing body of evidence that is changing the way we think about astrocytes and how the brain works.”

Smith’s lab investigates how breathing is controlled by the rhythmic firing of neurons in the pre-Bötzinger complex, the brain’s breathing center that his lab helped discover. For this study, his team worked with Dr. Alexander Gourine of University College London whose lab found that astrocytes in neighboring parts of the brain may regulate breathing by sensing changes in blood carbon dioxide levels.

At least half of the brain is composed of cells called glia and most of them are astrocytes. Recently, scientists have shown that astrocytes may communicate like neurons by shooting off, or releasing, chemical messages, called transmitters, to neighboring cells.

In this study, the scientists tested the role of astrocytes in breathing by genetically modifying the ability of astrocytes in the pre-Bötzinger complex to release transmitters. When they hushed the astrocytes in rats by reducing transmitter release, the rats breathed and sighed at a lower rate than normal. In contrast, if they made the astrocytes chattier by increasing transmission, the rats breathed at higher resting rates and sighed more often.