Twin Clinical Center Exhibits Honor NIH Scientists

The Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum opened twin historical exhibits in the Clinical Center in May honoring two NIH greats: Dr. Christian Anfinsen, who shared the 1972 Nobel Prize in chemistry; and Dr. Michael Potter, winner of a 1984 Lasker Award. Anfinsen and Potter began their careers at NIH in the 1950s, when molecular biology and genetics were new fields. They expanded both fields by asking questions that led to deeper understanding of basic biological functions. Their commitment to science influenced their personal lives as well.

The exhibit “Christian Boehmer Anfinsen: Protein Folding and the Nobel Prize” shows how Anfinsen answered the questions: How do amino acids come together to create proteins? How do proteins then fold into their specific shapes? What do those shapes have to do with the actual function of a protein? Anfinsen answered those questions as he learned how to unfold and refold proteins to determine their amino acid chains and created the first enzyme synthesized in a laboratory.

He believed that discovering how proteins work in the body was as important as breaking the genetic code because, after all, the entire purpose of DNA is to encode the production of proteins from amino acids. He stated the bold idea in his 1959 book, The Molecular Basis of Evolution, that comparative protein chemistry combined with genetics would provide insights into evolution. He aimed to take basic molecular biology to what he called “molecular engineering.”

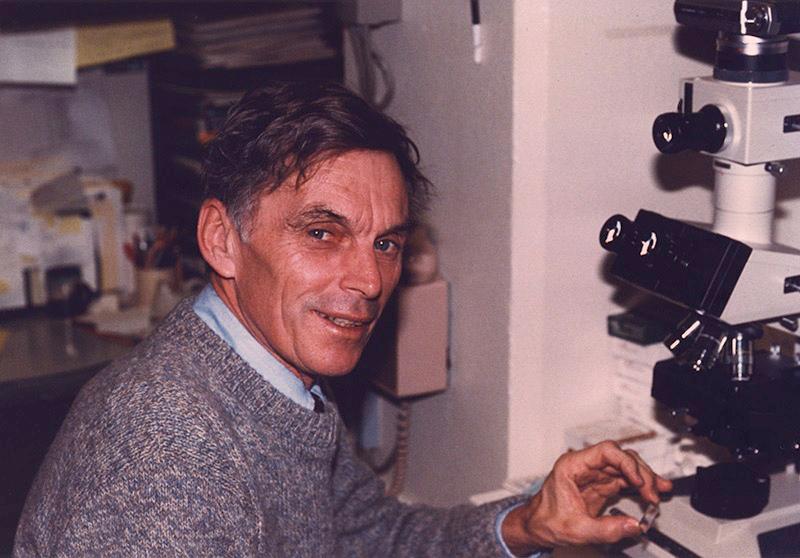

The exhibit “Curiosity and Collaboration: The Work of Michael Potter” shows how answering basic questions motivated Potter as well: How does the body defend itself from bacteria, viruses and foreign cells? And what causes cancer? Potter and his collaborators discovered how immunoglobulins work, how genes and viruses can interact to cause cancer and how to grow cancerous cells in a petri dish to study, instead of in an animal. He prepared the field for the discovery of monoclonal antibodies, one of the most important tools today in medical research. Generous with his material, Potter believed that knowledge, instead of acknowledgement, was the goal of science.

The twin exhibits also present personal glimpses of each man’s life. One of the objects in the Anfinsen exhibit is his typewriter and some of the letters he wrote in support of scientists around the world. Potter’s love of the natural world, particularly the beach, and some examples of his artistic talent are displayed.

The history office’s goal is to present a glimpse into NIH’s rich history of achievements that have been important for basic and clinical research. The exhibits were developed and designed by the NIH Stetten Museum with sponsorship from NCI, NIDDK and NHLBI. Some of the images and objects were generously loaned by NLM.