In a Heartbeat

Don’t Fear AEDs—You Might Save a Life

Photo: Dana Talesnik

When someone collapses in sudden cardiac arrest, every moment counts. Using an AED (automated external defibrillator) and administering CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) until medical help arrives can make all the difference. But would the typical bystander get over the initial shock of the situation to intervene?

AEDs, which assess heart rhythm and can send an electric shock to the heart, might appear intimidating to the untrained onlooker, but these portable devices are remarkably simple to use. Across NIH, on and off campus, there are 374 fully automatic AEDs, often located near elevators, including 94 in the Clinical Center alone.

“These devices are safe,” said Juli Egebrecht, director, basic life support training at NIH, who started teaching CPR in 1972 and has worked at NIH for more than 30 years. “They will only shock people who need it.”

Bystanders also need not worry, she said. The shocking field of the adhesive pads is surrounded by an insulated strip with minimal leakage.

“The hardest thing is to get over the initial ‘Oh my gosh’ situation,” said Egebrecht. “The AED talks with specific instructions and nags you until you do it.”

Annually, more than 18,000 Americans go into cardiac arrest in public places, and an estimated 1,700 lives are saved by bystanders using AEDs. A recent Johns Hopkins study, partly funded by NHLBI and NINDS, revealed significantly higher patient survival rates when a bystander used an AED while waiting for emergency medical personnel to arrive. What’s more, many of those patients survive cardiac arrest with minimal disability.

All campus AEDs are inspected monthly, said Egebrecht. The unit chirps and flashes when the battery gets low. “For all the problems you might think could happen to a life-saving device,” she said, “people have done their homework and had the forethought to figure out how to keep them viable, active, easy and safe to use.”

A bystander’s first reaction to someone lying unconscious should be to check for responsiveness. If the person isn’t breathing or there’s an irregular pulse, or none at all, yell for help and dial, or ask someone nearby to call, 911.

Photo: Dana Talesnik

When reaching for the door to an AED box, don’t fear the alarm. It’s not that loud and serves to alert people around you to an emergency.

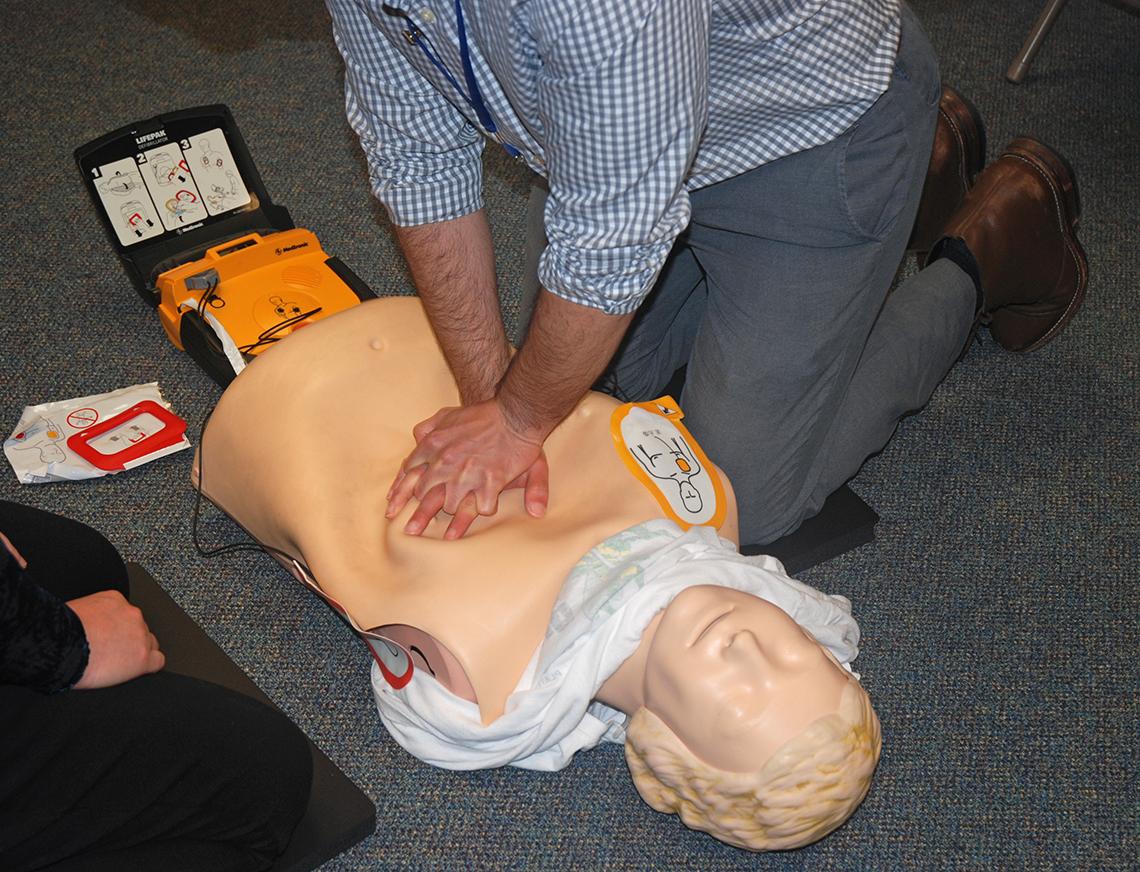

Next, grab the AED. Semi-automated AED models turn on at the push of a button; fully automatic ones turn on just by opening the lid; voice prompts then offer step-by-step instructions. There’s an enclosed pouch with scissors to cut the patient’s clothing and the talking AED coach tells you exactly where to place the two adhesive pads. The AED then analyzes the heart rhythm and will tell you whether a shock is advised.

At that point, it’s safe to start chest compressions while the AED is charging, says Egebrecht. After each shock, the machine prompts the rescuer to give CPR and chimes like a metronome so the CPR-giver can give compressions to the beat.

Photo: Dana Talesnik

“By the fourth cycle of chest compressions, medical help should be arriving,” said Michael Dunn, an occupational health & safety manager at NIH who oversees NIH’s CPR training for non-medical personnel. “The best chance for survival is keeping the compressions going.

“But, if you don’t know what you’re doing,” warned Dunn, “go find someone who does. Don’t apply CPR if you’re untrained; you can do harm.”

Keeping blood circulating is critical, said Dunn. That’s why current CPR training focuses on chest compressions, not on giving breaths. “Keeping blood flowing extends the life of vital organs,” he said. “The longer you keep the vital organs alive, the better chance you have for recovery from a cardiac arrest incident.”

There’s no time like the present to learn CPR. NIH offers free CPR training to all interested personnel. Classes cover adult CPR and using an AED. Egebrecht teaches CPR to health care providers from current clinicians to trainees aspiring to get into a medical field. Dunn manages and leads lay responder classes for administrative staff.

To learn more or sign up, visit https://www.ors.od.nih.gov/sr/dohs/safety/Training/Pages/aedlocations.aspx.

For anyone seeking additional training, the American Heart Association offers Heartsaver classes that cover child and infant CPR, first aid and related training. See https://cpr.heart.org.

Said Dunn, “If you have CPR training, you’re considered one of the assets in your building who can save a life.”