Senescent Cells Block Cancer, Contribute to Aging

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

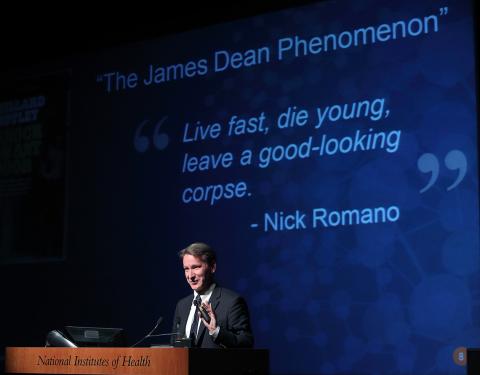

A process that prevents damaged cells from dividing also prevents the development of cancer, said NCI director Dr. Ned Sharpless. But as these cells build up over time, they might contribute to diseases associated with advanced age.

“There’s an explicit trade-off between aging and cancer,” Sharpless said recently at the Florence Mahoney Lecture on Aging, sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and part of the NIH Director’s Wednesday Afternoon Lecture Series. “You can do things about aging, but often they’ll promote cancer and you can do things about cancer, but often they’ll promote aging.”

Cells that can no longer divide but continue to function are called senescent cells. They are beneficial in certain situations, suppressing tumor formation and aiding in wound-healing, Sharpless said.

Dr. Leonard Hayflick first observed senescent cells in vivo in the early 1960s. He discovered that certain cells stop dividing when they become damaged. The cells don’t die; rather, they continue to be metabolically active.

A tumor-suppressor gene called p16INK4a (p16) activates the senescence process once it senses damage to a cell. Sharpless observed that mice lacking the gene didn’t age as fast as mice with p16. However, those without the gene got cancer at higher rates.

“We think senescent cells hang around a long time and do stuff that’s undesirable and contribute to the pathology associated with advanced age,” he said.

Because senescent cells don’t divide, they can’t regenerate tissue, Sharpless said. They interfere with important functions. For example, senescent cells might get in the way and contribute to the size of atherosclerotic plaques. These cells also make cytokines, which can damage other cells and contribute to chronic inflammation during later life.

Although the immune system can clear senescent cells, its ability to do so is limited and may decrease with age.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

In mouse studies, scientists are studying several approaches to clearing senescent cells. If researchers can destroy them using “senolytic” drugs, for example, they believe they might be able to reverse some types of age-related pathology.

Sharpless, who in addition to directing NCI is chief of the aging biology and cancer section in NIA’S Laboratory of Genetics and Genomics, said chemotherapy can trigger cellular senescence. Although chemotherapy can treat cancers, it also spurs an increase in senescent cells, he said. The amount of senescent cells varies from patient to patient.

“These cells appear to drive some of the long-term toxicities of cancer chemotherapy,” he said.

For example, chemotherapy can interfere with the body’s ability to produce blood cells, Sharpless explained. Oncologists who treat cancer patients are not surprised by his results. This suggests DNA-damaging chemotherapy made the marrow biologically older, on the order of 20 years.

Many patients who undergo chemotherapy experience debilitating fatigue for months. Sharpless noted that “chemotherapy-induced fatigue is a limiting toxicity in many patients.” He described a means to reduce the toxicity of chemotherapy for cancer patients, in a way to protect their hematopoietic stem cells.

In a footnote, Sharpless mentioned that in early November, the field of geriatric oncology lost a valuable contributor with the death of Dr. Arti Hurria, director of City of Hope’s Center for Cancer and Aging in Duarte, Calif.

Sharpless called Hurria’s death “devastating for the field because Arti was a particularly good leader and a really forceful advocate for this topic. She will be sorely missed.”

There is “a real shortage,” Sharpless concluded, of students who are interested in basic and translational research in geriatric oncology.

“We are thankful to Dr. Sharpless for giving an engaging presentation about his research on tumor suppression and aging,” said NIA director Dr. Richard Hodes. “His work in geriatric oncology, in particular regarding tumor suppressor molecules, is relevant and of interest to many NIH institutes. His research has helped show that while senescent cell production is helpful with wound-healing and tumor suppression, this process also contributes to multiple aging-related diseases.”