Barabino Sorts Out Mechanics of Sickle Cell Disease

Photo: Dr. Marie A. Bernard

Traffic jams are bad enough—remember the mass campus exit during Jan. 7’s snow?—but what if they occurred in blood vessels throughout the organs of your body, from the eyes, to the liver, to the gall bladder, on down?

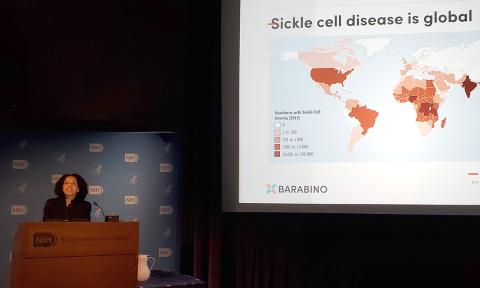

That is what sickle cell crisis inflicts on the millions of people worldwide who have sickle cell disease (SCD), including some 100,000 Americans, said Dr. Gilda Barabino, dean of engineering at the City College of New York, at a Jan. 28 talk in the Wednesday Afternoon Lecture Series.

SCD is a painful disease caused by a single amino acid that has gone awry and typically results in 30 years less life expectancy for those who have it, said Barabino. Cases of SCD are predicted to rise by 30 percent between 2010 and 2050, she added.

Normal red blood cells are like the fittest person at your gym, the one who is endlessly strong and flexible.

“The red blood cell is a marvel in both structure and function,” said Barabino, who directs CCNY’s Laboratory on Vascular and Orthopedic Tissue Engineering Research. “It has a bi-concave discoidal shape that permits the membrane to deform while maintaining a constant surface area without stretching. Its flexible dumbbell shape allows it to pass through vessels with a diameter half the size of the red blood cell itself.”

But in SCD, red blood cells become deformed in low-oxygen conditions and adopt a sickle shape, their once-flexible membranes distorted due to polymerization of beta hemoglobin. Like a pileup of bumper cars in an arcade, the sickled cells block traffic, leading to vaso-occlusion, a hallmark of SCD.

Sickled cells are both stiff and sticky, exhibiting abnormal adhesion, Barabino noted. “Adhesion can impede the passage of other cells, leading to obstruction, and permanent damage can result.”

Photo: Dr. Mia Rochelle Lowden

The interior traffic jams can include adherent reticulocytes—younger red blood cells—and white cells, said Barabino, in addition to cells that are stiffened and misshapen due to the aggregation of hemoglobin molecules. Combined, these factors result in increased blood viscosity, or thickness, and impaired blood flow.

Currently, there are two FDA-approved drugs for treating SCD, hydroxyurea and glutamine. The former appears to reduce cell adhesion within 2 weeks of administration to SCD patients, said Barabino.

There are curative therapies, too, including transfusion and bone marrow transplantation. But they are expensive and ill-suited to the low-income parts of the world where SCD is most common.

Barabino recounted attendance at an international SCD meeting held in Cotonou, the largest city in the Republic of Benin, Africa, where world leaders in SCD research met at the country’s National Sickle Cell Center.

“What stood out for me was the level of incidence,” Barabino said, “and the lack of access to diagnosis and treatment. There were stories of mothers who couldn’t bring their children in to be evaluated. Many died before coming in for diagnosis.”

To illustrate the acuteness of the suffering associated with SCD, Barabino showed a painting by Haitian artist Hertz Nazaire of a face literally blossoming with pain, watered by its own tears.

In studies of red blood cell subpopulations, Barabino and her colleagues have identified four types, distinguished by red cell density, that correlate with cell age. They have noticed the marginating of stiffer cells to vessel walls, while the more flexible cells flow within the middle of a vessel.

Their goal is to exploit this mechanical finding by extracting from blood the stiffer cells. The ability to discriminate between affected and non-affected cells also offers a way to monitor disease progression, she explained.

Her team is also studying bone involvement in SCD, which has some commonalities with osteoporosis, Barabino said. Using a transgenic mouse model of SCD that replicates the organ damage suffered by humans, the scientists are gaining insights into bone pathology.

Photo: Dr. Mia Rochelle Lowden

In examinations of the microarchitecture of mouse femoral trabecular bone and cortical bone, the researchers have discovered loss of volume, thickness and strength in SCD mice as compared to controls. Bone quality rapidly declines with age, said Barabino. “Older [SCD-affected] bones are particularly deteriorated.”

When her team introduced L-glutamine powder to the rodents’ drinking water, the animals benefited in bone volume and reduced damage to liver and spleen.

Barabino is confident that studies of cell and tissue biomechanics will provide telltale signs of SCD progression and help investigators discriminate between health and disease.

Looking to the future, she is heartened by the NHLBI-led Cure Sickle Cell Initiative at NIH, “which links lots of partners. A comprehensive approach is needed for such a complex disorder.”

There is also an American Society of Hematology SCD Initiative and a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine Project on SCD, on whose governing committee she sits.

“That is also a very comprehensive project, and a report is due soon,” Barabino said.

Media attention to SCD is also burgeoning at the moment, with the recent 60 Minutes special on NIH trials and a January article in the New York Times on a 16-year-old girl participating in the world’s first SCD gene therapy trial.

“There is great promise, but a lot of unknowns,” Barabino concluded, stressing the value of different perspectives when attacking a medical problem.

The full talk is available at https://videocast.nih.gov/summary.asp?live=35109&bhcp=1.