Ultimate Survivor Recalls CC Study 65 Years Ago

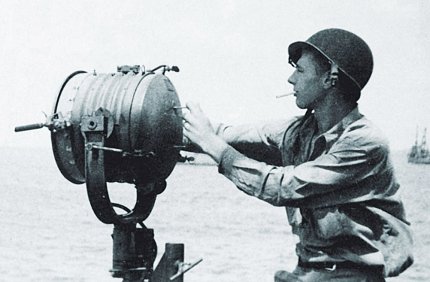

Leonard Gardner had already survived the “day that will live in infamy.” He’d been a signalman aboard the USS Reid when Pearl Harbor was bombed on Dec. 7, 1941. Gardner had lived through battles at Guadalcanal, Okinawa and other significant World War II actions too. Several years past his military service, however, following a routine visit to the doctor, Gardner once again faced imminent mortality—but he didn’t know it until many months later.

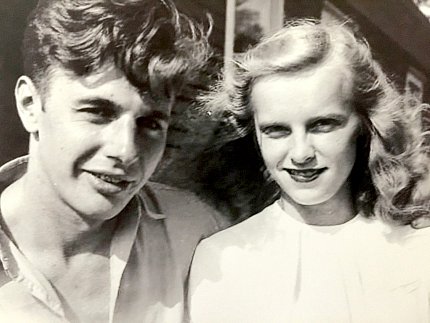

It was late in 1954. The 33-year-old former sailor and his wife Doris were living in Morningside, a Prince George’s County Md., community developed especially for WWII veterans. The couple—already parents to three young children—was expecting another little one in spring. Still employed by the Navy department, only now as a civilian, Gardner went to his family physician for a checkup.

“I told him I had trouble crossing my legs,” recalled Gardner, now a 98-year-old Palmyra, Va., resident along with Doris, now 94. “He immediately poked my legs and determined I had collected a lot of fluid. He told me to get over to the hospital right away. I felt all right, just kinda logy. Apparently, I’d accumulated quite a bit of fluid and didn’t realize it.”

The doctor sent Gardner immediately to Providence Hospital in northeast Washington, D.C.

“[The doctor] wasn’t particularly forthright with me, but he told my wife that it didn’t look good and that I probably wasn’t going to make it. [He] gave up on me, although he didn’t tell me at the time.”

Not long after admitting Gardner, Providence discharged him. His condition confounded them and there was nothing more they could do for him.

“I don’t think they knew what he had,” said Doris. “I don’t think they knew what the problem was.”

He took extended sick leave from his job. “It was just marking time for me,” Len remembered. “I didn’t know I was terminal, but my wife did.”

About a month later, a coworker called the Gardners at home. She’d learned of Len’s illness and wondered whether he ought to try to get examined at NIH. “She was aware of some of the studies they were doing out there and suggested I go be a test patient,” Len said.

The family doctor wasn’t keen on the idea. But after some convincing, he agreed to recommend Gardner to NIH. The Clinical Center admitted Len in January 1955.

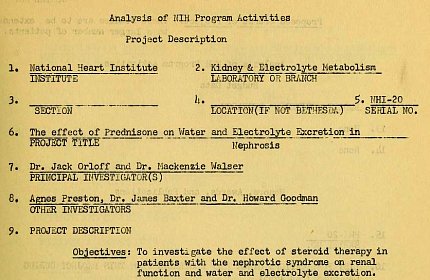

Timing was ideal. The hospital had just opened about 18 months earlier. A team at the National Heart Institute, led by principal investigator (and future NHLBI scientific director) Dr. Jack Orloff, was investigating “the effect of steroid therapy in patients with the nephrotic syndrome on renal function and water and electrolyte excretion,” according to a 1954 Annual Report of Program Activities published by NIH. Co-PI Dr. Mackenzie Walser, Agnes Preston, Dr. James Baxter and Dr. Howard Goodman, who Gardner remembers, rounded out the research group.

“I became one of the several patients that they had that they were testing for our reaction to a new drug that was being promoted that hadn’t been released to the general medical community, but they were experimenting with it and it was called meticorten [prednisone, a corticosteroid],” said Len, who was diagnosed with nephrosis, a kidney disease.

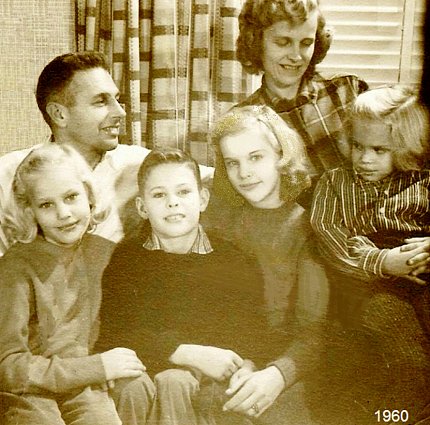

“Only the NIH group identified what the problem was,” noted Doris, who, pregnant and with 3 youngsters underfoot, was able to visit Len only once a week. There were no large highways, no Capital Beltway and sparse public transportation from Morningside to the still mostly rural NIH campus back then. Commuting “all the way across town was rather a tedious drive,” the Gardners recalled. Also, the hospital didn’t allow kids, so Doris had to get a babysitter.

As for the CC experience itself, Len said, “There were about 6 or 8 patients there that [the doctors] were playing around with. And I was in there for about 7 to 10 days being monitored. I remember they’d come around in the morning—a group of doctors—and they’d poke me in my backbone and they’d poke my legs. They determined that I had so many pounds of fluid in me. After about a week or 10 days, they decided to put me on this program of meticorten. That was taken by pill. And I’ll be darned if it didn’t take immediate effect on me. All of a sudden, all my fluids started flowing out…I guess I had a couple of gallons in me. I lost weight so fast! It happened so fast it was just a miracle.”

Retired geriatrician Dr. Gordon Margolin, who at age 96 volunteers at the Office of NIH History, was a fellow in the kidney disease lab at Boston’s Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in the early 1950s. He remembers that cortisone and its derivatives had only recently been found to be “a replenishment for adrenal hormones that were missing in Addison’s disease or adrenal insufficiency. Everybody got very excited about the drug. Almost every week at medical grand rounds they’d present a case of some kind of disease that they tried treating with cortisone. It was like a miracle. Almost every week we were seeing cures that we didn’t expect. And suddenly this drug, which had just been discovered—or this hormone, which had just been synthesized—became a fantastic and useful therapy for almost everything.”

Gardner remembers taking meticorten for about 2 years.

“But not every day,” Doris explained. “Gradually it was reduced, and eventually he was an outpatient for a while. He was in the hospital until May or June, when they finally released him.” It was only then that he learned how sick and close to death he had been.

“I was [at NIH] when our child was born, so a neighbor had to take my wife to the hospital for the birth,” Len remembered. “I was out of work for about 6 months.”

The life-saving treatments came with side effects as well. “The drug gave me a hump on my back and my breasts blew up,” Len recalled. “He got very fat in the face too,” Doris added.

There have been no renal issues since Gardner’s participation in the study concluded. “The treatment at NIH took care of my kidney problem,” he said recently. “I am now 98, almost 99, and have the final stages of COPD.”

Gardner’s most vibrant memory of his Clinical Center stay, however, is neither the periodic prodding by health care staff, nor the discomfort that often accompanies serious illness nor even the triumph of being a medical research success story. What he chiefly recalls is the tremendous impact the ordeal had on Doris.

“I remember after I got out, my wife really kind of broke down,” he said. “It had been such a stress for her. She had been told I was terminal and she was pregnant. She didn’t have any idea how she was going to live with 4 children—all of them under 10. She didn’t know what her future was.”

“Anyway it’s turned out okay,” concluded Doris, summing up her husband’s survival through war and illness. “It’s all history now. He was like a cat with 9 lives there for a while. We got very lucky.”