An International Problem

NIH Pioneers Detection of Patients’ Risk of Suicide

NIH’s pioneering role in detecting suicide risk within the medical setting—in both children and adults—was the focus of a Clinical Center Grand Rounds webcast on Sept. 16, held in observance of Suicide Prevention Month.

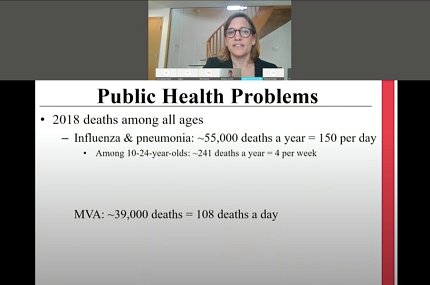

The presentation “Suicide Prevention: From Research to Practice at NIH and Beyond” featured three speakers who addressed an international public health problem. According to 2018 global data, suicide is the 10th leading cause of death for people of all ages, but the second leading cause for youth.

A highly stigmatizing act to contemplate or attempt, suicide claimed more than 48,000 lives in 2018. That’s 132 deaths each day, with 18 a day occurring in youth. In the period 1999 to 2017, the rate in youth jumped “a staggering 225 percent,” said Dr. Lisa Horowitz, staff scientist/clinical psychologist and director of patient safety & quality in NIMH’s Intramural Research Program. Rates are highest in minority and native populations, she added.

The most potent risk factor for suicide is a previous attempt, she said. Mental illness is also a risk factor; most who die by suicide have a diagnosed mental health concern but many do not, which is why it is important to screen universally.

Along with increased use of alcohol and drugs, and irregularities with respect to sleep—either too much or too little—it is talking about wanting to die that is the clearest warning of suicide, she explained.

It was a 2005 suicide in the then newly opened Clinical Research Center that galvanized the NIH effort to screen for suicide in the medical setting, said Horowitz. Such events are “rare and devastating in a hospital setting,” she said. And not all suicides in hospitals involve patients with behavioral issues; about 14 percent occur in non-behavioral health settings.

“Under-detection is a terrible problem,” Horowitz said. “Most [health care] settings don’t screen for [suicide].”

What clinical researchers sought to create was a brief and accurate tool that staff—mainly nurses—could employ upon patient intake. They developed the ASQ (Ask Suicide-Screening Questions) tool, which within about 20 seconds poses 4-5 questions whose answers have proven to be reliable indicators of suicide risk.

ASQ is now in the public domain and has been translated in 16 languages, reported Horowitz. There is an ASQ toolkit (www.nimh.nih.gov/ASQ) that includes videos and scripts for staff. If a patient screens positive, there is a defined pathway for further care.

The plan to screen CC patients began around 2011, starting with a pilot feasibility study in adults, which led to a multisite research study for adult medical patients that began at the CC in 2014, said Horowitz. In 2016, the CC began an effort to screen all patients, as evidence accumulated that the ASQ protocol was effective for both youth and adults.

“I feel that screening at the Clinical Center is important,” said second presenter Barbara Jordan, service chief for nursing operations in the NIH nursing department and acting service chief for neuroscience, behavioral health and pediatrics at the CC. “I was a critical care nurse for most of my career, and I saw patients who had made unsuccessful [suicide] attempts. There is sometimes a cynicism on the part of health care providers. The stigma associated with suicide is still very real.”

She continued: “Our patients often have devastating diagnoses, and therefore may be more at-risk for suicide attempts.”

In her experience, patients with behavioral diagnoses often were screened for suicide, but not medical/surgical patients. In 2016, she led a multidisciplinary team that included NIMH to develop implementation policies and procedures on screening all inpatients at the Clinical Center.

“The electronic health record [EHR] is vital to the process,” she said. Using the CC’s Clinical Research Information System (CRIS), the team taught nurses to screen patients by following a script that provided pop-up guidance on what to do next, given a patient’s answers to questions.

If a patient had acute thoughts of suicide, that was considered an emergency requiring one-to-one monitoring followed by a psychiatric evaluation to ensure safety; she noted that acute positive screens are very rare among medical patients.

A non-acute positive screen requires further evaluation from Clinical Center social workers, with notification to the primary care team, Jordan explained.

When it was clear that the pilot screening program in adults was effective, the NIH team knew they had to focus next on patients ages 10-24, using the ASQ.

Some subtleties developed over time in the two age groups. Whereas refusal to answer a question in youth is considered a positive response, that’s not necessarily true in adults, Jordan said. And privacy emerged as an important condition—a patient of any age is less forthcoming if there are other people, especially parents, in the room.

There is also the problem of patients who are not cognitively able to be screened, Jordan said.

Her team developed online training modules and in-person sessions were created so that nurses feel comfortable and supported during screening. They also developed educational materials for patients, parents and social workers.

On Sept. 29, the CC adopted one tool—ASQ—for both youth and adults. Plans are underway to screen outpatients in 2021.

The session’s final speaker was social worker Deborah Snyder, senior adviser to NIMH’s clinical director and deputy director of patient safety & quality for the institute.

As screening guidelines developed, she explained, the NIMH team wondered if patients would find it acceptable to be asked such questions. And would staff mind inquiring?

In a pilot quality improvement project involving 331 adult patients, 13 screened positive for suicide risk, which is about the typical prevalence in a health care setting, said Snyder—about 3-4 percent. But 87 percent said they were comfortable being asked, versus 60 percent of nurses who were less comfortable asking; 100 percent of social workers were on board with it.

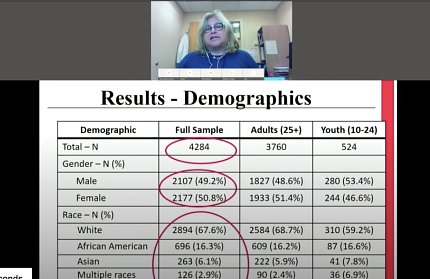

Starting in April 2017, universal screening in the Clinical Center began in adult patients, with youth being added 6 months later. Out of 4,284 patients screened (3,760 adults, 524 youth), 97.7 percent screened negative for suicide risk over a year; 2.3 percent were positive, including a single acute-positive case.

“That is 97 people [81 adults, 16 youth] who might not have been detected otherwise,” said Snyder. Most follow-up involved CC social workers, who were trained to conduct a brief suicide safety assessment, which guides next steps.

In May, the NIH team published a journal article on universal suicide screening and its value in health care settings. Whereas in 2008, such screening was conducted at only a handful of sites in the U.S., it has now spread not only nationwide, but also globally, said Snyder.

She emphasized the importance of stakeholder endorsement: “Clinician champions are critical,” she said, “and training and re-training are crucial…Screening is feasible and easy, and valid.”

The presentations left time for a single question from the audience: What if a patient doesn’t tell the truth?

“We are capturing a lot of people at risk,” said Horowitz. “Most people [considering suicide] want to speak about it. You should always ask directly. Remember to ask!”