Fighting Misinformation

Covid-19 Pandemic Is More Than a Scientific Problem, Says Jha

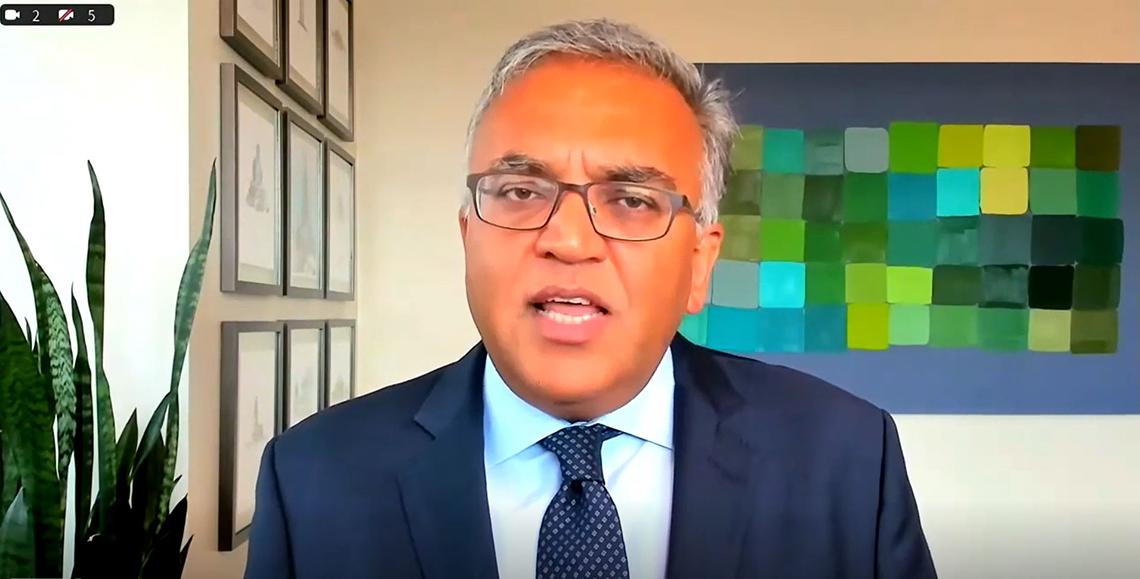

The Covid-19 pandemic is more than a public health challenge. It’s also a societal and economic challenge, said Dr. Ashish Jha, during a Contemporary Clinical Medicine: Great Teachers Grand Rounds lecture on Sept. 8.

“Science and facts certainly matter a lot,” said Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health. “If we want to reach people, change behavior and provoke people to act in certain ways, it requires a lot more than sharing knowledge, data and facts. It actually requires understanding what people value and find meaningful.”

Since SARS-CoV-2 was first discovered in late 2019, scientists have made extraordinary progress against the virus that causes Covid-19. Three safe and effective Covid-19 vaccines are available in the U.S. and several more are available around the world.

By the end of the year, Jha estimated more than 9.5 billion vaccine doses will be administered. By the middle of 2022, 14 billion doses will be administered.

Researchers also have learned how to treat patients who have the virus. They’ve studied the effectiveness of masks, learned how to improve indoor air quality and developed accurate and fast diagnostic tests. Scientists have also made progress on the development of therapeutics, although it’s been slower than in other areas.

“This is extraordinary progress in 18 months,” he noted. “What the global scientific community has done is nothing short of breathtaking.”

Experts from outside the traditional biomedical research community have contributed to the effort, Jha said. Computer scientists, for example, modeled the disease. Economists weighed the pros and cons of public health policies and sociologists have raised important societal questions.

And yet, still more than a third of Americans are saying “no thanks” to a vaccine that is available in pharmacies across the country. This is happening while 1,500 Americans are dying every day from Covid-19 and hospitals reach capacity.

“The pandemic has created a breeding ground for both misinformation and disinformation,” he explained.

While misinformation and disinformation campaigns are not new, they feature new wrinkles in 2021.

Most Americans get their news from television, social media platforms and websites or apps. What first appears as a lie on Twitter or Facebook, for instance, will be featured on television or in the newspaper the next day. Then, people talk about what they saw with their friends or family, who they trust. What results is widely circulated misinformation.

“We all live in information echo chambers,” Jha said. “Information we see is amplified and bounced off of other sources and reinforces for us that the information we are seeing is the whole truth and complete picture.”

Both foreign agents and homegrown actors run highly coordinated disinformation campaigns. The goal of most campaigns is to make money.

Many public health officials are not good at communicating uncertainty, Jha said. In February and March 2020, many officials advised the public not to wear masks because it was wrongly thought that SARS-CoV-2 couldn’t spread asymptomatically.

“We should not overcall things and we’ve got to be very careful about what we know and don’t know,” he cautioned. “And we should level with people about what we don’t know.”

There is a flipside, which can also get officials in trouble.

When the vaccine rollout first began, some scientists said they didn’t know whether vaccines would decrease transmission because they didn’t have real-world data. Consequently, some people heard that vaccines do not reduce transmission. He advised that scientists should’ve said something like, “we don’t know for sure. But most vaccines do, and I have every reason to believe this one will as well.”

Scientists often fail to consider people’s lived experiences, he explained. In March and April 2020, public health officials advised people to stay home and physically distance. For many, however, following those guidelines wasn’t possible. Essential workers, for example, couldn’t stay at home.

“It was a failure in our community to understand what people could and could not do,” he said. “We needed to do a better job of explaining that ‘if you could stay home, you should try to stay home. But if you can’t stay home, here are the things you need to be doing to keep yourself and your family safe.’”

To fight this “infodemic,” Jha advised public health officials to get out of their own echo chambers and seek perspectives different from their own. Understanding why people think what they think is important.

Additionally, officials must do a better job of explaining that science is a process. Advice changes as new data emerges.

Recently, someone who received the single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine asked Jha whether they needed an additional dose.

“The short answer is, we don’t know,” he responded. “But here’s how we will know, here’s when we will, here’s why that will be a better time to make a decision.”

A lot of officials still expect the public to trust experts and science. For many Americans, that’s enough. Others don’t trust expert advice. Those pushing misinformation have created a participatory way of engaging people.

“Science is not a single fact,” he said. “People trust things that they can verify and participate in. We have to do a much, much better job of creating participatory science.”

Failing to counter misinformation effectively will result in more cases and hospitalizations, he said.

There aren’t enough researchers fighting against misinformation. He urged scientists to engage the public using high-quality information.

“Think about the conversations you would have around the dinner table or with your friends,” Jha concluded. “You need to have those conversations in the grocery stores, your local community and you need to have those conversations on local TV.”