Unique Population

COLBOS Study Reveals Mysteries of Alzheimer’s Disease

Photo: Lisa Helfert

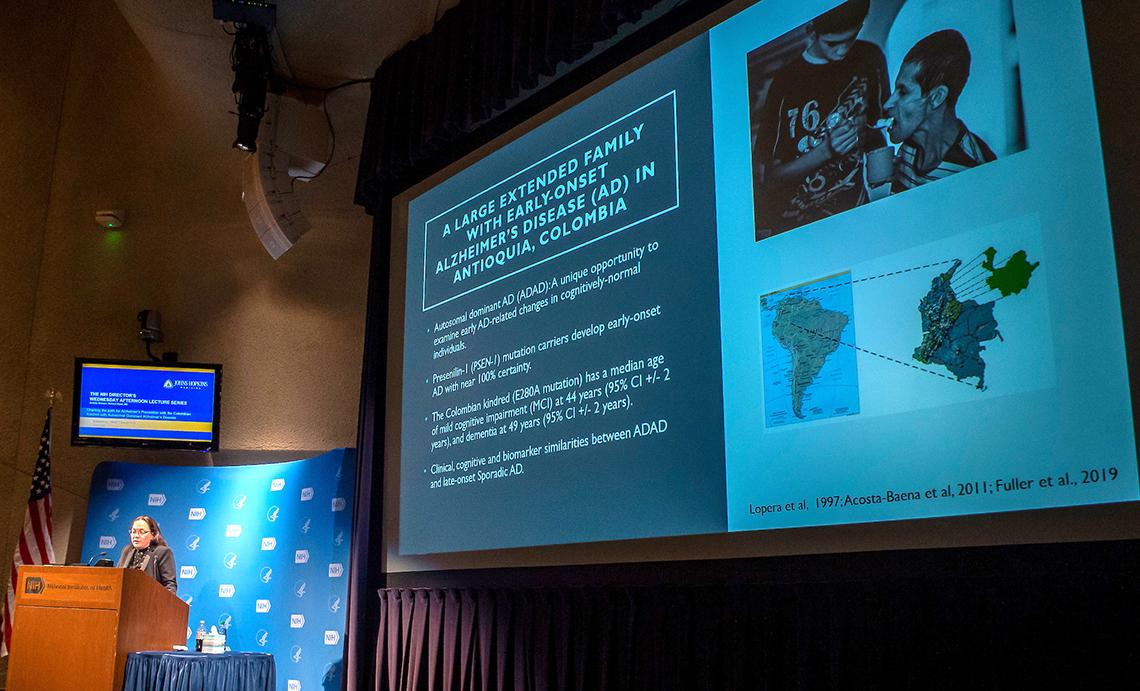

A Colombian family with a rare mutation for early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease has provided researchers a unique opportunity to study the disease years before symptoms begin, said Dr. Yakeel T. Quiroz, during the recent Florence Mahoney Lecture on Aging, part of the Wednesday Afternoon Lecture Series.

By identifying the preclinical stages of the disorder, researchers hope to “delay the clinical onset and prevent Alzheimer’s disease and dementia altogether,” said Quiroz, associate professor in the departments of psychiatry and neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

As a college student, more than 20 years ago, she began studying together with Prof. Francisco Lopera an extended family group of 6,000 people in Antioquia, Colombia. Many of them carry a rare, genetic mutation for early-onset AD, called the Presenilin-1 (PSEN1) mutation. Carriers develop the disease with almost 100 percent certainty. On average, they experience cognitive impairment at age 45 and dementia at age 50.

Quiroz has followed individuals from these families who are destined to develop AD and dementia decades before they show symptoms. “We have a window of opportunity to characterize some of the earliest preclinical changes,” she noted.

Photo: Lisa Helfert

There are several clinical, cognitive and biomarker similarities between early-onset AD and sporadic late-onset AD, the more common form of the disease. Age, family history and heredity are the most important risk factors for late-onset AD, Quiroz said. Most people diagnosed with late-onset AD are over 65 years of age.

Those with the PSEN1 mutation undergo brain changes years before they begin to exhibit symptoms, she said. In children, boys with the mutation had decreased working memory compared to girls with the mutation. This suggests a “sex-specific genetic risk” in early-life cognitive abilities. Brain abnormalities, such as changes in brain activation and brain volume, begin as young as age 9.

“The increased risk of cognitive abilities in boys may have important implications when we’re thinking about learning and academic achievement,” Quiroz said.

Photo: Lisa Helfert

In 2014, Quiroz launched COLBOS (Colombia-Boston), a collaborative, longitudinal biomarker study between the Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia, and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. Every 2 years, Colombians from the PSEN1 families travel to the United States, where doctors collect health data and perform advanced neuroimaging examinations.

COLBOS has shown that the amyloid protein begins accumulating in carriers around age 28, Quiroz said. The protein clumps together to form plaques that build up between neurons. Amyloid is one of two proteins—the other tau—that accumulate in the brains of patients with AD.

The tau protein starts accumulating in their late 30s, Quiroz explained. This occurs a few years before they exhibit symptoms. Tau forms threads and tangles together, which disrupts brain connectivity. Increased levels of tau only occur in parts of the brain where amyloid was present. It’s linked to memory decline.

“The accumulation of amyloid appears to be a steady process, beginning as early as 20 years before dementia onset,” she explained. “In contrast, tau pathology is very rapid.”

There are two blood biomarkers that might help researchers detect AD before symptoms begin. Carriers of the mutation have a higher concentration of neurofilament light chain (NfL) and ptau217. Both are proteins. These blood biomarkers might allow individuals who don’t have access to tau or amyloid brain imaging an opportunity to get an earlier AD diagnosis, she said.

Photo: Lisa Helfert

One woman who participated in the COLBOS study carried the PSEN1 mutation. However, she did not develop AD symptoms until she was in her 70s, almost 30 years after the expected age of onset for other carriers. Quiroz said her brain had high levels of amyloid and very low levels of tau.

Genetic testing revealed the woman had two copies of the APOE Christchurch mutation, which seems to have protected her brain against tau accumulation. Quiroz’s team has developed an antibody that mimics the mutation’s function. Researchers are studying the antibody to determine whether it might be a promising therapeutic.

“Families with autosomal dominant mutations provide a unique opportunity to study disease progression from preclinical to clinical stages, [and] develop and improve measures for early detection, novel interventions and clinical trials,” Quiroz concluded.

Mahoney lectures are sponsored by NIA and named in honor of Florence Stephenson Mahoney (1899–2002), who devoted much of her life to successfully advocating for the creation of NIA and increased support for NIH.

The lecture can be viewed at https://videocast.nih.gov/summary.asp?live=44272.