Meeting Our Makers

NIH Inventors Introduced in New Series

Photo: TRIFF/SHUTTERSHOCK

In recognition of the National Week of Makers, celebrated annually in June, the NIH Record is kicking off a new series featuring the “makers” of NIH—intramural researchers who devise exciting new drugs, devices, applications, methods and other products.

In this first installment, we meet two scientists at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) who are developing new contraceptive options.

First of its Kind

Photo: Diana Blithe

“I’m usually a glass half-empty type of person, but [with this product] I’m more like ¾ full,” NICHD’s Dr. Diana Blithe said recently.

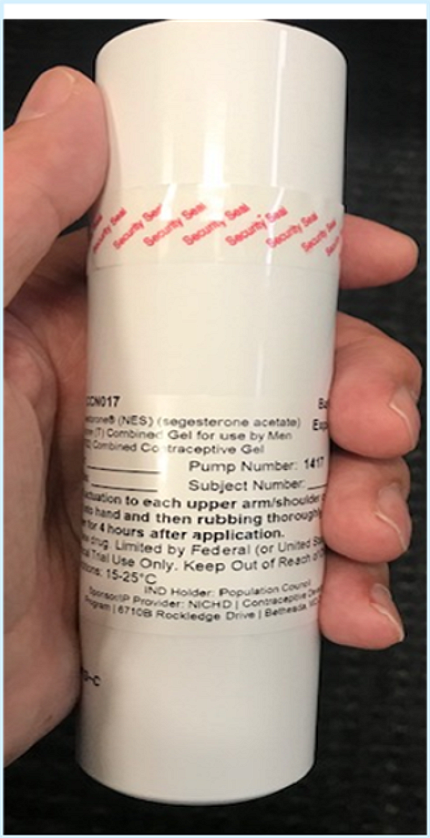

What has her feeling so optimistic? NES/T, a revolutionary new contraceptive for men, is close to clearing a crucial clinical trial step. It is a transdermal gel that users apply daily to their back and shoulders to suppress sperm production.

Blithe is the program chief of NICHD’s Contraceptive Development Program (CDP). She and her team conduct translational and clinical research to develop novel methods of contraception for women and men. The NES/T study is a collaboration with the Population Council and the developers of Nestorone.

Her product is the first of its kind: A male hormonal contraceptive absorbed through the skin to block sperm production while still maintaining functional levels of testosterone elsewhere in the body.

NES/T accomplishes this through a combination of two hormones. Progestin (the “NES” comes from Nestorone, the brand name of the progestin in the product) acts on the brain to block pituitary hormones that control natural testosterone production in the testes. The “T” stands for replacement testosterone.

Photo: Diana Blithe

Under normal circumstances, the testes maintain high testosterone levels (about 100 times higher than blood levels) to support sperm production. By blocking testosterone production locally, sperm production falls to low or nonexistent levels. However, the male body needs to maintain some level of testosterone for normal functioning—which is where the replacement testosterone comes in. It “replace[s] the blood testosterone at the normal physiologic level” while keeping the testes level low enough that it can’t restart sperm production, Blithe explained. Sperm counts recover to normal levels after participants cease using the gel.

So, why gel instead of a pill?

“Pill forms of testosterone are not absorbed well,” Blithe explained. In trials, participants needed to take multiple doses a day to achieve the same effects as the transdermal gel.

In the current study, daily application of the gel reduced participants’ sperm counts to less than 1 million per milliliter, which is low enough to be considered contraceptive.

Studies of hormonal control of sperm production have been around for more than 60 years, but with little success until recently. “We knew we could do it, but the delivery was the issue,” Blithe recalled.

Two components inspired the gel. Replacement testosterone gel has been around since about 2002; Blithe got the idea to combine it with Nestorone in 2004, when CDP and the Population Council were working on a different product that contained Nesterone.

NES/T now is in phase 2B of clinical trials that evaluates the efficacy of the method to prevent pregnancy in couples.

“The effectiveness is much higher than we expected,” Blithe said.

Photo: Diana Blithe

Current study participants hail from sites around the world. Couples use the gel as their only form of contraceptive for one year (with additional time to monitor sperm decline and rebound before and after the year of gel-only contraceptive usage).

The next step, Blithe said, is to take the data to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and find out what additional data they would need to approve the product.

The significance of this product is not lost on Blithe. In surveys over the past 20 years, about 50% of men surveyed have expressed the desire for a reversible form of contraceptive. Now that it is a reality, men who have used the gel are overwhelmingly impressed with the drug’s effectiveness and safety.

“It’s very reassuring that we have so many men who would like to continue to use it,” Blithe said.

One aspect she didn’t realize at first was the benefit to the female partner in being able to stop whatever contraceptive she was using.

“The anxiety of having to go back on a [contraceptive] method that isn’t perfect for her is palpable,” Blithe noted. “It’s a women’s health issue as well as something for men.”

Removing Hurdles

Photo: Min Lee

Dr. Min Lee said he “never came across things [he] thought would make it as a product” until two certain products evolved in NICHD’s Contraceptive Development Program (CDP): NES/T and an injectable contraceptive for women that Lee co-invented.

A Ph.D. and chemist with CDP, Lee has a long career in drug discovery and development, so that statement carries weight. He came to the extramural program in NICHD from the private sector 13 years ago and joined CDP in 2017.

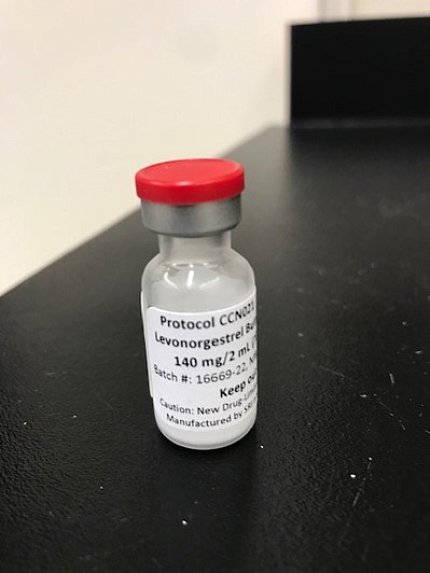

Since then, he has been working on his invention: levonorgestrel butanoate (LB). Levonorgestrel butanoate is an injectable prodrug (an inactive drug that is metabolized into its active form) that breaks down in the body to provide levonorgestrel, the active drug. It is a progestin-only contraceptive being developed as an alternative to Depo-Provera, the only other injectable birth control for women.

Depo-Provera has several unwanted side effects for some women—weight gain, mood swings, decreased bone mineral density—and also may be less effective in women who are obese.

Additionally, other forms of hormonal contraceptives that contain estrogen are often not recommended for obese women because of conditions like diabetes and hypertension that can co-occur with obesity.

Levonorgestrel is a strong progestin (a synthetic version of the human hormone progesterone) that works to prevent pregnancy.

In LB, the levonorgestrel “acts as a negative feedback loop…by telling the brain it has enough progestin and can stop making its own progesterone,” Lee explained. Through series of signaling cascades, the lack of natural progesterone inhibits ovulation.

The road to the current LB began in the 1980s, when NICHD, the World Health Organization (WHO) and other collaborators were working together to develop an injectable contraceptive using levonorgestrel butanoate. That project fell through and NICHD picked it up again in the early 2000s. They tweaked the formulation to make it more stable and last longer. The butanoate prodrug portion of LB was the key to improving the drug’s lifespan.

Lee and co-inventors then discovered something else surprising—LB was also effective for longer duration when it was injected subcutaneously (SQ) rather than as an intramuscular (IM) shot.

“We did not expect to see this,” Lee recalled. “We knew this was a significant breakthrough when we saw the SQ data.”

Photo: Min Lee

IM shots lasted about two months. Conversely, the SQ injections last between three and five months. In the current phase of clinical trials (2A), the CDP clinical team dropped the IM version of the drug entirely and are now focusing their efforts on the SQ version.

In addition, the SQ delivery route is exciting because women can self-administer the drug. An IM shot must be given by a trained medical professional, but SQ injections don’t have the same limitations.

Lee’s product is poised to have a big impact. Many women face obstacles coming to a doctor’s office every few months to stay up to date on their contraceptive regimen. Also, about one-third of women who are of reproductive age are obese.

Unplanned pregnancies in the U.S. make up about 45 percent of pregnancies each year, Lee noted, and he hopes LB will fill the niche for a safer, more convenient alternative to current injectable contraceptives.

“This will be a good option for women because it gives them more freedom,” Lee said. “It will remove a lot of hurdles.”