Sister Study Turns 20

NIEHS’s Sandler Expounds on Environmental Risks of Breast Cancer

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

This year, nearly 300,000 women will have been diagnosed with breast cancer in the U.S. While annual incidence has leveled off, it is increasing for some groups and breast cancer still accounts for 30% of all new cancer cases among women, many of whom had no family history of the disease.

Researchers have long attributed breast cancer to a combination of genetic, hormonal, lifestyle and environmental factors, though discerning precise environmental triggers remains tricky. An ongoing NIH research effort continues to shed light on those triggers.

In the early 2000s, public concerns over the rising rates of breast cancer inspired the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) to take action.

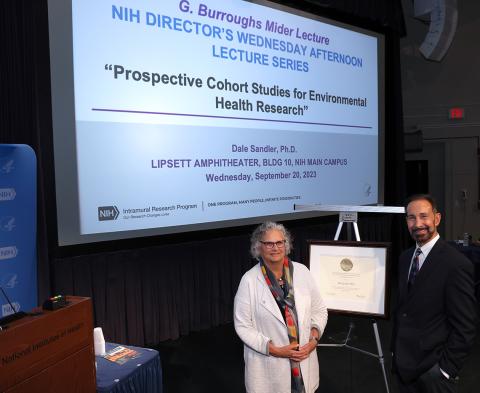

“Our institute leadership challenged us to do something new and gave us the opportunity to think big,” said Dr. Dale Sandler, chief of NIEHS’s Epidemiology Branch, who recently delivered the annual G. Burroughs Mider Lecture—part of the Wednesday Afternoon Lecture Series—during the NIH Research Festival.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of that landmark effort called the Sister Study, the largest national cohort of its kind to explore environmental causes of breast cancer, from pollution to personal care products.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

“Women, especially, and environmental groups, were concerned not only about the steep rise in breast cancer incidence but also, in parallel, a steep rise in the use of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in personal care products and common household products,” said Sandler.

For developing a breast cancer cohort, Sandler’s team deemed sisters of women who had breast cancer the ideal population to track over time.

“It occurred to us that sisters have twice the risk of developing breast cancer,” she said. And sisters likely share early-life experiences and exposures that could yield novel clues. “This would give us greater power to study gene-environment interactions and also to identify unusual or previously unknown environmental risks.”

Starting in 2003, over several years, the Sister Study enrolled 50,884 sisters of women who had breast cancer. All of the study participants had no breast cancer at the time of enrollment, though more than 4,000 of them have since been diagnosed with breast cancer.

Heartening to researchers is the sustained participation. The follow-up response rate has been 85-95% over time, not surprising given the emotional connection the sisters have to this research. The high response rate continues to drive a wealth of data.

Participants submit annual updates along with detailed questionnaires every three years. Women diagnosed with breast cancer also provide medical records. At enrollment, the researchers visited the homes of every participant to take clinical measurements, collect biological specimens—blood, urine, nail clippings—and even house dust.

“We collect extensive amounts of data across the lifespan,” Sandler said, from health to residential histories. The goal is to understand “periods of enhanced susceptibility. For example, puberty is a period of rapid breast changes and growth and exposures during this time may be particularly relevant to breast cancer risk later in life.”

In analyzing early-life events, researchers found those who experienced early-life trauma—such as sexual trauma or household dysfunction—had elevated breast cancer risk.

“Part of the impetus for [probing trauma] was, when we met with interest groups in designing the study, many wanted to know if stress caused their breast cancer,” recounted Sandler.

The researchers also found that such early-life environmental factors as exposure to a parent’s tobacco use or living on or near a heavily trafficked road were associated with increased breast cancer risk.

“Where you live matters,” Sandler said. “Where you live is a source of exposure to multiple stressors. It also determines your access to health care and other resources and services.”

Overall, breast cancer rates actually are higher among people with higher education and income levels, Sandler noted. The researchers found evidence however that a specific type, estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer, is more common among women living in disadvantaged communities.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Among lifestyle factors and chemical exposures, the Sister Study released noteworthy findings earlier this year involving the effects of hair products on breast cancer risk. Participants were asked how frequently they used hair dyes and straighteners in adolescence and adulthood. The findings reflect stark racial disparities.

Researchers found using hair straighteners at least four times a year increased breast cancer risk by 35%. This statistic is especially concerning for Black women, many of whom use hair straighteners throughout their lives, starting at a young age.

Permanent hair dyes showed a 7% increased breast cancer risk for White women and a staggering 45% increased risk for Black women, Sandler said, “potentially reflecting the different products marketed to Black women as well as differences in hair texture and absorption.”

Racial disparities are an ongoing area of concern. The incidence rate of breast cancer in Black women is climbing and approaching that of White women. And, Sandler noted, “the mortality rate still remains disturbingly higher in Black women than in others.”

Subsets of the larger cohort are used for comparison and gaining deeper insights into noncancerous conditions and other health outcomes. Data on dietary patterns—sleep and light exposure at night, for example—are revealing more about obesity risk.

Obese women who are postmenopausal have a higher risk of breast cancer. Obese women are also at higher risk for type 2 diabetes, a disease that raises the risk of some types of breast cancer.

Going forward, Sandler’s team is expanding questionnaire topics to include hair texture, sunscreen use, housing characteristics and climate resilience. They’re also planning to collect more biologic samples from subsets of participants—including women who developed breast cancer during follow-up—to better understand changes in exposures over time in relation to breast cancer risk.

“This time, we’re going to focus on making sure we include a larger sample of our Black and Hispanic participants,” she said, “and also focus on the rare breast cancer subtypes.”

To learn more about Sister Study participants and findings, visit https://sisterstudy.niehs.nih.gov.