Topol Discusses Potential of AI to Transform Medicine

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to shape the future of human health and medicine.

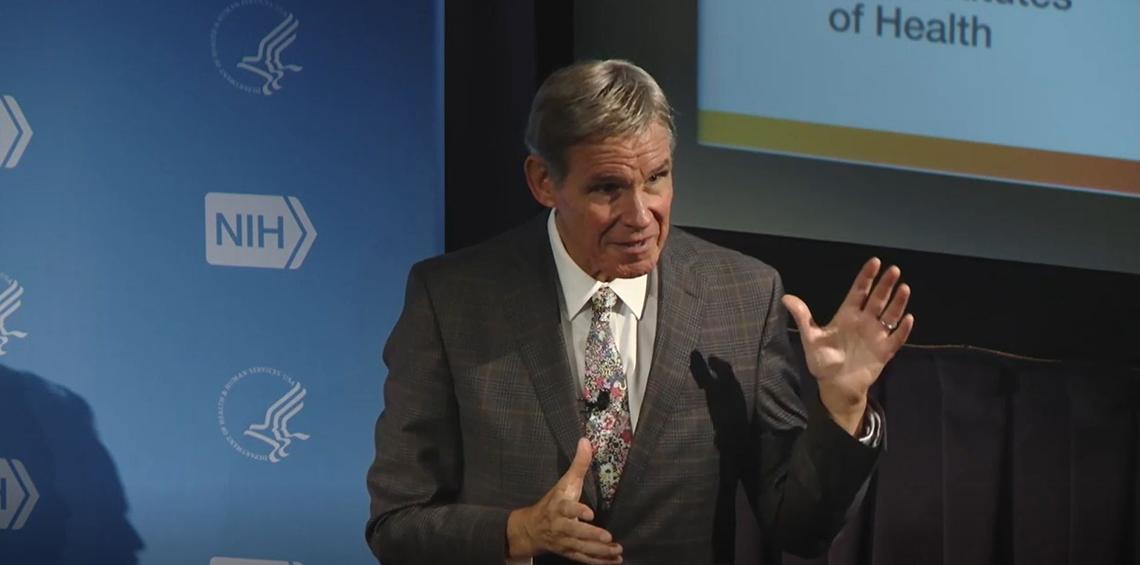

“Machine eyes will see things that humans will never see. It’s actually quite extraordinary,” said Dr. Eric Topol, executive vice president and professor of molecular medicine at Scripps Research Institute and founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute. He spoke at a recent Contemporary Clinical Medicine: Great Teachers Grand Rounds lecture held in Lipsett Amphitheater.

Advancements in graphics processing units (GPUs) have ushered in a new era of computing. Originally designed for rendering 3D graphics and pixels to display on a screen, GPUs can run many, many operations all at once. This trait makes them highly effective at handling large amounts of data and algorithms required for AI models.

A few years ago, medical AI models relied on the availability of labeled datasets to predict outcomes and recognize patterns. Typically, these models were trained using a supervised-learning paradigm, where they learn to map an input—usually a medical image like a chest x-ray—to an output—the prediction of a disease. These models are “unimodal supervised AI.”

“We learned from that time that every type of medical scan could get an AI interpretation that would be quite good, comparable and complementary to those from clinicians,” Topol said.

In 2019, a New York University study found that a chest X-ray AI tool could catch a cancerous nodule in the lung a radiologist missed. The largest randomized trial using AI to date was for breast cancer detection. He said the study of 80,000 people in Sweden found that AI-assisted reading of mammograms helped doctors detect cancer at faster and higher rates compared to an AI reading or a radiologist alone.

Other studies have shown that AI scans of retinal images can now predict the risk of many conditions, including diabetes, high blood pressure, kidney, liver and gall bladder diseases, coronary artery disease, heart attack, stroke, hyperlipidemia, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

“Who would’ve ever thought that through the retina—the gateway to the human body—we could detect all of these things,” Topol said.

There are many randomized, controlled trials evaluating AI in clinical practices, he said. The largest proportion of these studies takes place in gastroenterology. There are almost 1,000 Food and Drug Administration-approved AI models. Few of these models, however, are in use.

Since the emergence of the AI chatbot ChatGPT in late 2022, more and more AI models are “multi-modal self-supervised.” Topol said these models “learn from themselves, rather than requiring annotations by experts.” They can handle various data types, such as text, images and audio.

The latest version of ChatGPT has more than one trillion parameters, or connections, and requires more than 24,000 GPUs. Topol said training these models on data can cost millions of dollars because of the massive amount of data needed.

Despite these limitations, the development of multi-modal self-supervised AI is setting up new applications in health care and medicine. For instance, the newest AI models for cancer prognosis and detection can predict the diagnosis, including the genetic mutations involved, and the prognosis.

There are many stories where patients asked chatbots for help with their diagnosis. In one case, a boy with chronic pain saw 17 doctors in three years. No doctor could diagnose him. Finally, his mother asked ChatGPT about her son’s symptoms. Within seconds, the chatbot suggested a diagnosis of spina bifida occulta. A neurosurgeon confirmed the diagnosis.

During appointments with patients, he said doctors of all specialties often spend so much time taking notes and compiling data that they don’t have the time to ask patients questions or conduct adequate physical exams.

“This is not the right type of medicine that we want to practice,” he said. “We want to have presence, trust and a bond that’s ameliorated and built upon during a visit.”

Many healthcare systems across the country now use AI dictation programs to help doctors with administrative tasks, including note-taking, prescription refills and billing.

Doctors must be aware of the downsides of adopting AI technologies, Topol said. The models can generate incorrect or misleading results. These are called AI hallucinations or confabulations. Also, AI models can produce results that reflect human bias. And, finally, some clinicians believe AI could replace them (It won’t, Topol noted).

In the future, physicians will be able to use AI to forecast a patient’s individual risk for many types of diseases, he said. Right now, pancreatic cancer is almost always diagnosed late, when it has progressed to stage three or four. Studies have shown that these models can be trained to detect the cancer years before it manifests.

“This is a really exciting time in medicine,” he concluded. “We’ve never had this opportunity before.”