History Comes Alive

Students Learn Lessons from Previous Pandemic

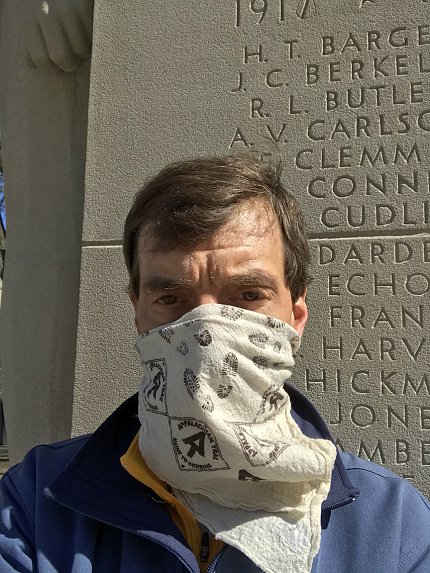

Last fall, when Virginia Tech professor Dr. E. Thomas Ewing assigned his history class a research project on the 1918 Spanish flu, he never imagined the country would be in the middle of another global pandemic by the spring semester. Now, their project has taken on new meaning.

After the Covid-19 outbreak closed their campus in March, Ewing’s 12 undergraduates became geographically dispersed and thrust into other unexpected situations.

“What these students have gone through in some ways is a microcosm of what the whole country is going through,” said Ewing at an Apr. 29 NLM History of Medicine virtual research symposium that was part of the ongoing NLM/National Endowment for the Humanities partnership to collaborate on research, education and career initiatives.

Despite the challenges, these students—six of whom discussed their findings that afternoon—continued their research with renewed vigor, searching for clues from a century ago to inform their understanding of the current pandemic.

“I was trying to do something different in this course,” said Ewing, “which is to ask how we can use numbers, statistics and data to cultivate a sense of empathetic understanding in history.”

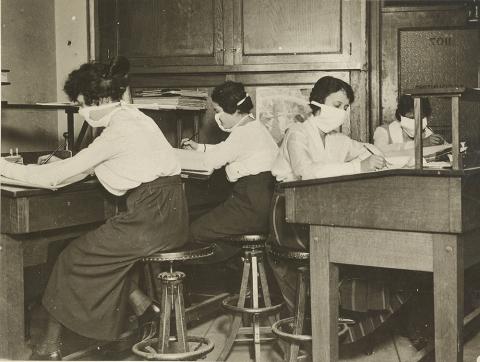

For example, he displayed an archival photo of women at their desks wearing masks. Probing a bit deeper, the photo tells a rich story about conditions at that time.

Photo: National Archives

The young women were office clerks, among the highest casualties of the Spanish flu by occupation. Published in a New York newspaper, the photo appeared at a time when more than 10,000 Americans were dying daily. And, unusual for a flu, the mortality rate was high among people in their 20s and 30s.

“If you were in New York City on Oct. 16, 1918, you were in the midst of a very frightening increase in the number of people around you dying from this disease,” noted Ewing.

More stories and lessons would unfold as his students set to work mining historical data and documents.

Reporting on the Flu

One team of students surveyed U.S. newspapers in 12 cities, exploring the frequency and tone of flu coverage.

Though it competed with coverage of World War I, the Spanish flu dominated the news and made frequent front-page headlines, particularly during the peak month of October 1918.

“Each city had many examples of flashy and alarming headlines that reported tragedies and could create panic in the public,” said student Louisa Glazunova. But by late fall 1918, more headlines featured preventive measures and a calmer tone to allay public fears.

“[Some] stories and the word choices really shocked the readers into taking precautions more seriously during the peaks of the influenza,” said student Fiona Tran. Later, the tone changed, reassuring the public that their cooperation was effective.

In 1918, the timeframe seemed to dictate the tone of stories, the two students observed, whereas during the current covid crisis, different tones emanate from competing news sources. In both cases, they postulated, when and how news gets released can affect public reaction and compliance with health guidelines.

Recording Outcomes

Even a century ago, such guidelines as social distancing, mask-wearing and school and business closures were recommended—not necessarily enforced—to curb the viral outbreak.

Students Jacob Beachley and Yash Joshi examined vital statistics, newspapers and other documents to ascertain whether social-distancing measures had an impact. They focused on Indiana and Missouri, two similarly sized states that had similar outbreak timelines and flu death rates near the national average.

Unexpectedly, in both states, they found that counties with the smallest populations had the highest death rates. Was this anomaly due to lack of medical care, an overburdened medical system, or lax social-distancing implementation? The team plans to further investigate.

Also, although the two states both issued statewide shutdowns early in October 1918, students noted another curious finding.

“Despite Indiana taking statewide action before Missouri, [Indiana] still had massively higher cases and case rates…than Missouri,” said Beachley. What happened? Indiana lifted restrictions too soon.

“The fact that Indiana opened up social distancing too early led to a resurgence in cases,” said Joshi, noting that the state had to reinstitute its public gatherings ban. “This extended Indiana’s timeline of the crisis.”

Their research offers a forewarning in the current crisis: Social distancing resulted in lower infection rates and death tolls in 1918, said Beachley and Joshi, whereas ending countermeasures too soon could spike death rates and lead to reinstituted bans and a longer recovery.

Reopening and Remembering

In November 1918, as Spanish flu cases declined, states cautiously eased restrictions. By late December, 6 weeks after the last cases appeared, all restrictions—mask-wearing, public gathering bans, forced quarantines, limited travel between cities—were lifted and businesses, schools and other public places fully reopened. Many states experienced a second wave in late winter into spring 1919, but the worst was over, reported students Katie Kromer and Alessia Scotto.

Yet, in many ways, the worst wasn’t over, they said. Countless people lost loved ones; the emotional and physical devastation remained. One newspaper in Harrisburg, Pa., reported that the flu left 50,000 children orphaned across the state.

“Even after the flu was gone, it couldn’t just be forgotten and things could not go back to normal,” said Scotto, “because life was completely changed for a lot of people due to the pandemic.”

There are echoes of the 1918 flu pandemic in the current crisis. History reminds us that actions and behaviors have consequences. Today, as then, we watch for a steady decline in cases before cautiously reopening society.

Today, though, noted Kromer, technologic advances help us track viral spread and identify hotspots in real time, providing almost instant access to data and other urgent information.

Access to historical source materials has also evolved. Not long ago, scholars and students would fumble with microfilm reels. Now, many records are digitized. For these projects, the students relied heavily on Chronicling America, an online newspaper repository managed by the Library of Congress and National Endowment for the Humanities. It is available at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/.

Today’s digital media will be tomorrow’s historical record for future scholars, observed Dr. Jeffrey Reznick, chief of NLM’s History of Medicine Division, during the symposium.

“A future generation will look back on these [and similar] presentations,” said Reznick, “as examples of historical research at a historic time, reflecting on the past, through the lens of the present and with an eye to the future.”