From Risk Factors to Genetics

NHLBI Marks Year 70 of Iconic Framingham Heart Study

Photo: Andrew Propp

Some 50 years ago, NIH researchers introduced two words into the American lexicon that flipped the public’s thinking about heart disease on its head—“risk factors.”

Those words emerged from the landmark Framingham Heart Study to characterize conditions that researchers discovered can increase a person’s likelihood of developing heart disease—high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol, then later, smoking, obesity, diabetes and physical inactivity. Before Framingham, researchers knew little about the causes of heart disease; the study’s early discoveries spurred development of new treatments and public health practices that have helped people get healthier and reduced deaths from heart disease.

That was the message delivered Feb. 1 by Framingham director Dr. Daniel Levy in a special lecture to mark the 70th anniversary of the long-term, multigenerational study, now a joint project of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Boston University. The talk, held in Natcher Conference Center, was the first in a yearlong series of science lectures organized by NHLBI, which is also celebrating its 70th anniversary this year.

During his lecture, “Unraveling the Mysteries of Cardiovascular Disease: Lessons from NHLBI’s Framingham Heart Study,” Levy described the history of the study and its many contributions to heart health. He also highlighted new research developments, including the study’s more recent focus on genetic risk factors and their use to advance precision medicine.

Photo: Andrew Propp

“Framingham has been an exceptional contribution to medical science,” said Levy, who is also chief of NHLBI’s Population Sciences Branch and professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine. “It has provided an immeasurable return on investment for NHLBI, both on the extramural side and the intramural side.”

Levy noted that around 1900, most people thought of heart disease as an inevitable part of aging. At the time, the leading causes of death were infectious diseases—namely, pneumonia, tuberculosis and infectious diarrhea. These infections, he added, contributed to the relatively short life expectancy of Americans—about 50 years. But by the mid-1940s, nearly half the deaths in the United States could be traced to a new culprit—heart disease.

Levy pointed out that public attention to heart disease grew after the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in April 1945. Records show that during his presidency, Roosevelt’s blood pressure had increased steadily until it reached what now are recognized as highly dangerous levels shortly before his sudden death from a stroke.

“Did he die out of the blue, with no warning signs whatsoever?” Levy asked the audience. “I think the evidence suggests that there were plenty of warning signs.” Yet because little was understood about high blood pressure (hypertension) as a risk factor for heart disease and because there were few anti-hypertensive treatments at that time, Roosevelt did not receive the care available today, Levy said.

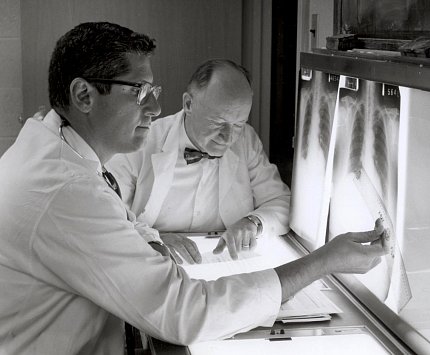

Photo: Hecht collection, Office of NIH History

It was against this backdrop that federal health officials in 1948 decided to establish NHLBI (then called the National Heart Institute) and also launch the Framingham Heart Study. Designed initially as a prevention program, the study included 5,200 adult men and women with no signs of heart disease, living in Framingham, Mass.

With the aid of extensive health data collection (including physical activity records and food intake surveys) and early computing technology, clues began to emerge about the underlying causes of heart disease in the study participants.

Then in 1961, a major turning point came with the publication of an article in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Titled “Factors of Risk in the Development of Coronary Heart Disease—6-Year Follow-up Experience,” the study introduced the phrase “factors of risk,” which was inverted to create the now-common term “risk factors” for heart disease; the authors have since been credited for its origin.

Photo: Hecht collection, Office of NIH History

In that seminal publication, the study identified high blood pressure and high cholesterol as risk factors for developing heart disease. The finding “opened up the field of preventive cardiology,” Levy said. In subsequent years, researchers identified many additional risk factors for heart disease, including cigarette smoking and diabetes.

Levy noted that Framingham was almost de-funded in 1969, as reported in the New York Times. However, influential politicians weighed in, citing its impact on understanding heart disease and its potential to save lives.

Not only was the program saved, but by 1971, Framingham began to recruit a second generation of participants, called the Offspring cohort. The newly evolved study focused on the familial basis of heart disease. It also introduced new screening tools, including echocardiograms and treadmill stress testing.

By 1999, the Washington Post declared the study number 4 on a list of the most important medical advances of the 20th century.

“That was rather flattering, but Framingham has never rested on its laurels,” Levy said. “New opportunities in science have led to new scientific research in Framingham.”

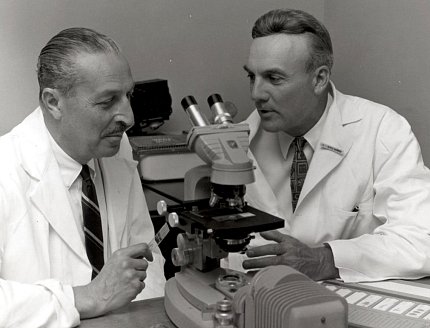

The completion of the Human Genome Project almost two decades ago, led by physician-geneticist (and now NIH director) Dr. Francis Collins, helped create a new direction for the study. By 2002, Framingham had recruited a third-generation cohort with a focus on genetic underpinnings of heart disease.

Photo: Andrew Propp

Since then, with advances in technology, the study has continued to expand and deepen its focus on genetics. NHLBI’s TOPMed (Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine) program, which includes whole-genome sequencing to uncover genetic mechanisms of disease, contains research data from 4,200 participants in Framingham. Many other groups worldwide have formed partnerships with investigators to further explore underlying factors of heart disease.

More recently, these studies have begun to reveal the genes that contribute to high blood pressure. Others are exploring biomarkers for atherosclerosis (cholesterol deposits in the arteries) and trying to identify new molecular targets to treat and prevent heart disease.

Seventy years after the study began, heart disease remains the leading cause of death in the U.S. But thanks largely to the Framingham study and our improved understanding of heart disease risks, deaths from heart disease have declined significantly. Levy noted that compared to 1968, when the rate of coronary heart disease deaths in the U.S. reached its peak, 1.4 million such deaths were averted in 2014 alone.

“We are reaching our stride and hope we will be able to continue those studies into the future,” Levy said.

The lecture is archived at https://videocast.nih.gov/summary.asp?Live=26979&bhcp=1.