Generosity of Spirit

How NIH’s Main Campus Came to Be in Bethesda

Have you ever wondered how the main NIH campus ended up in the middle of Bethesda? The answer is: generosity.

The Wilson family—Luke Ingalls (“Luke I.”), Helen and their son Luke—owned much of the land that NIH occupies. The core 70 acres was their estate, called Tree Tops. The main house, built by the Wilsons in 1926, is now Bldg. 15K, hidden in greenery up the hill from Bldg. 31.

The elder Luke helped manage his family’s international men’s clothing business, Wilson Brothers, and Helen was the daughter of Samuel Woodward, one of the owners of the venerable Woodward and Lothrop’s department stores in the Washington, D.C. area. They were a well-traveled family, having visited Europe dozens of times for business and pleasure—when you had to take a ship to Europe. They enjoyed European culture, food and diversity.

The Wilsons had friends of all kinds in many different countries. The elder Luke was a dedicated correspondent who developed several lasting friendships with various politicians including Franklin Roosevelt. The two began corresponding with each other when Roosevelt was governor of New York. Wilson often visited Roosevelt’s home in Hyde Park, N.Y. This friendship would become pivotal for establishing NIH in Bethesda.

Generosity was a foundational value of the Wilson family. For example, Helen met a pianist who did not own a piano, so she had one delivered to him. When the Wilsons decided they wanted to do something that would help others, they committed to donating their biggest asset—their land.

The problem was finding someone during the Depression of the 1930s to take it. A park for Montgomery County, a school to teach boys international cooperation instead of competition and a training center for teachers were some ideas pursued by the Wilsons but that the Depression made impossible. So elder Luke wrote to his friend, then-President Franklin Roosevelt, offering the land to the federal government, if feds had a good use for it. Roosevelt passed the letter along to Dr. Lewis Thompson, who was searching for a bigger and better place for NIH laboratories and animals than downtown Washington, D.C.

A research institute devoted to improving everyone’s health was a mission that suited the Wilsons, and they threw themselves into planning the layout of the campus with Thompson.

When father Luke died of bladder cancer just days before Congress established the National Cancer Institute in 1937, Helen added even more of their estate to the donation for Bldg. 6, which was dedicated to NCI. She lived out her days in the estate Lodge, which included the Flat, a guest house and greenhouse, the Cabin and a garage on 3.5 acres.

Helen and son Luke carried on the Wilson tradition of a generous spirit with his wife Ruth. The younger Luke was a pilot in WWII, and Helen and Ruth would host events for the soldiers and their families in the Cabin. They set the tone culturally for NIH in the early years by making their home a welcoming and comforting place for people.

Over the years, when son Luke’s family visited, they would stay in the Lodge, Cabin or Flat. For the family, the campus was an oasis of quiet and peace.

During the summer, they often spent nights on the porches of the residences, because there was no air conditioning. They could hear the crickets and take advantage of the breeze. Reading in the buildings’ window seats, even on the hottest days, also offered moments of cool relaxation. The family appreciated the bucolic environment, with its trees and ponds that were home to frogs and Koi.

After Luke died in 1985, Ruth remained until her death from falling down a flight of stairs at Calvin Baldwin’s on-campus house on Thanksgiving 1989. The family had several conversations with NIH to turn the remaining areas of the estate into a welcoming center and a place for families to stay while their loved ones were receiving treatment at NIH, but an agreement wasn’t reached. The family donated the remaining 3.5 acres and the homes to NIH.

In the span of one lifetime—that of son Luke—the Tree Tops estate of his parents would go from a wooded hideaway to a bustling campus of dozens of buildings employing thousands of people, all dedicated to fulfilling the Wilsons’ dream of making the world a better place for everyone.

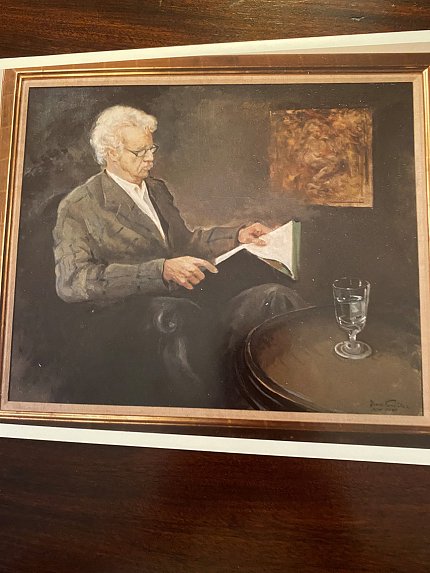

There was a painting of the younger Luke Wilson donated to NIH in 1990, which has been lost. Let the Office of NIH History know if you have seen it. Luke I. and Helen’s portraits are installed in Wilson Hall, Bldg. 1.

*Special to the NIH Record. Michele Lyons is associate director and curator, Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum. D.S. Wilson, a granddaughter-in-law of NIH’s generous patrons, serves as a volunteer with the office.