‘Haunted and Taunted’

‘Plague of Athens’ Cause Remains a Mystery

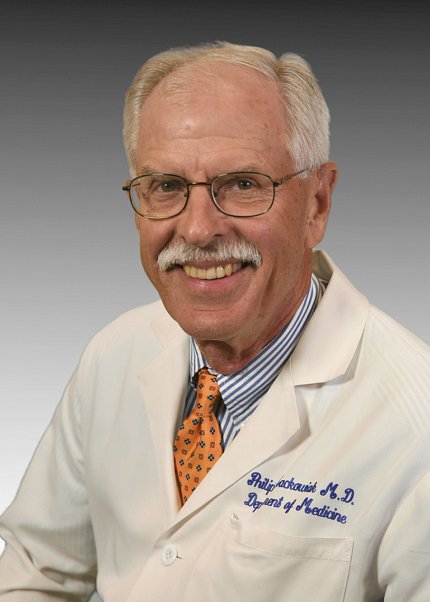

More than 2,500 years ago, a mysterious plague raged through Athens. As much as a quarter of the city’s population died, said Dr. Philip Mackowiak during a recent Contemporary Clinical Medicine/Great Teachers Grand Rounds in Lipsett Amphitheater.

“The mysterious outbreak was one of the first well-described pandemics. Despite 2,000 years of speculation, it’s yet to be diagnosed,” said Mackowiak, emeritus professor of medicine and the Carolyn Frenkil and Selvin Passen history of medicine scholar-in-residence at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

The plague swept away the “Golden Age of Athens.” The time preceding the pandemic was an “an amazingly productive time” for ancient Greece’s most famous and influential thinkers, he noted. Playwrights Aeschylus, Sophocles, Aristophanes and Euripides wrote some of Greece’s most famous dramas. Herodotus and Thucydides established history as an academic discipline. And Hippocrates laid the foundation for modern medicine.

This time period is sometimes called the “Age of Pericles,” a reference to the prominent Athenian politician, orator and military general. Under his leadership, Athens became an educational and cultural center and naval power. Pericles was responsible for construction of the Parthenon, a large, marbled temple on the Acropolis.

The growth of Athens alarmed Sparta, a rival city-state. When Spartans could no longer tolerate being a subject of Athens, they invaded the land surrounding Athens, noted Mackowiak. In 431 BCE, the Peloponnesian War began.

Athenians abandoned their farmland and retreated behind the walls of their city. Long walls connected Athens to the port city of Piraeus, so Pericles didn’t have to worry about running out of supplies. He also knew that Spartans had the stronger army, so he directed the Athenian navy to launch attacks against the Spartan army from the sea.

Photo: KAVALENKAVA/SHUTTERSTOCK

Almost immediately after the onset of the Peloponnesian War, the plague descended. It first arrived in Athens’ port and spread through the crowded city, Mackowiak said. At first, Athenians thought the Spartans poisoned their drinking water because it struck so suddenly.

A survivor of the disease, Thucydides described its clinical characteristics in his historical account of the war. The illness began suddenly with headache and inflammation of the eyes and throat. These symptoms were followed by sneezing, hoarseness and violent coughing. Vomiting and a generalized rash came next.

“There was fever, restlessness, sleeplessness and extreme thirst,” Mackowiak said. “There was also an aversion to covers and clothing. Victims had a desire to submerge themselves in water.”

In the disease’s final stages, people had diarrhea and, sometimes, blindness and necrosis. Those who survived developed immunity; however, they sometimes reported “profound amnesia,” upon recovery, Mackowiak added.

According to Thucydides, the pandemic originated in Africa and then worked its way through the Mediterranean. Case fatality rate was around 25%. The pandemic was most severe during the first year, before disappearing gradually. It’s believed Pericles died from it, “but we don’t know for certain,” Mackowiak clarified.

Throughout history, medical historians have speculated on the plague’s cause. They have suggested influenza with toxic shock, bubonic plague, measles, ergotism, epidemic typhus or smallpox.

Photo: THEASTOCK/SHUTTERSTOCK

“Most of the signs and symptoms Thucydides described are non-specific and could be seen in almost any disorder you want to mention,” Mackowiak said.

The key to diagnosis is the blistering rash Thucydides described. Based on that evidence, epidemic typhus and smallpox are the most likely causes of the plague.

Several symptoms victims experienced resembled typhus symptoms. The mortality rate for untreated typhus is 20 percent. However, the disease is caused by a bacteria called Rickettsia prowazekii. Typhus is spread to people through contact with body lice infected with the bacteria. Typhus is responsible for epidemics, not pandemics.

“It’s hard to imagine the entire eastern Mediterranean was infested with lice,” Mackowiak argued.

There’s more evidence against typhus, he said. Necrosis of the hands and feet would have occurred only in the winter months had typhus been the culprit. The plague ravaged Athens through the summer, when typhus infections typically wane. While typhus causes rashes, they are not the same type as the Athens cases the historian described.

Rather, Mackowiak believes the evidence, although not perfect, points to smallpox. A highly contagious infectious disease, smallpox killed, on average, three out of 10 people who contracted it. It has an incubation period of a week to 17 days, suggesting “that smallpox could’ve popped up very quickly in Piraeus during the war.”

Those who contract smallpox experience a severe headache, backache and fever for the first two to three days, followed by inflammation of the tongue, mouth and throat. Then, a rash appears. It first starts as small red spots before progressing to a blistering rash.

“The most damning evidence against smallpox is the absence of a backache, which is extremely common during the initial phase of smallpox,” Mackowiak said. “And Thucydides failed to describe pockmarks on the faces, which he couldn’t possibly have missed on the faces of patients who survived.”

It’s possible that the historian was one of the few patients who didn’t get a backache or pockmarks, so he didn’t think it was a problem. Also, physicians at the time were more interested in a disease’s prognosis rather than its outcome.

Modern medicine might one day reveal the mystery of the plague. Until then, “we’ll continue to be haunted and taunted,” Mackowiak concluded.