Harness the Power

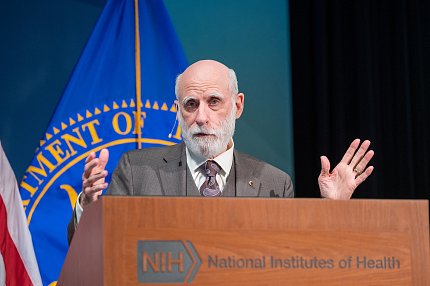

Chief Internet Evangelist Cerf Discusses AI at NIH

Photo: Leslie Kossoff

A world-renowned professor of any scientific field tends to draw a large NIH congregation composed of both seasoned believers as well as the merely intellectually curious. That’s what happened Mar. 19 as Google’s Chief Internet Evangelist Dr. Vinton Cerf took to the Masur Auditorium pulpit for the 2024 J. Edward Rall Cultural Lecture.

Titled the “Promises and Perils of AI in Biomedical Research and Health Care Delivery,” Cerf’s 15-minute “sermon”—his word—attracted a huge mix of IT experts, acolytes and neophytes and preceded a wide-ranging fireside chat with NIH Director Dr. Monica Bertagnolli.

“At NIH, I very much hope for all of us to work together to deliver evidence-based health care to all people and I’m very excited about how new techniques in machine learning and artificial intelligence can help us advance toward that goal,” Bertagnolli said, in opening remarks.

Introducing the guest speaker, she recalled her personal experience as a surgical oncologist and clinical investigator working to integrate standardized biomarkers into research trials—“a complicated enterprise trying to mix basic science endpoints including complex genomics and clinical data.”

At the lectern, Cerf described himself as “a networking guy, not an expert in AI.” However, he noted that Google, the company he’s worked for since 2005, has invested a lot of time and resources in the artificial intelligence field.

Emergence of AI

“Major progress has been made—especially in machine learning,” he said.

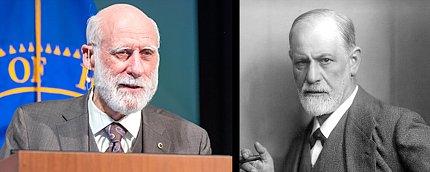

Photo: Leslie Kossoff

Cerf briefly retraced development of AI. The field began with problem-solving heuristic programming, “which roughly means sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t,” he quipped. “If it works all the time, that’s engineering. If it doesn’t, that’s artificial intelligence.”

Computing pioneers then advanced “expert systems,” or “if/then/else phrases” that would trigger each other, training programs toward a solution based on conditions that emerged.

That led to the earliest neural network, or “perceptron,” which was a single-layer algorithm that could not sense correlations well, Cerf explained.

Currently in AI evolution, we are at the Neural Networks stage, he said. Large language models use what’s called “generative pre-trained transformer” (GPT) technology to process natural speech, dialect, semantics and syntax.

‘Unbelievably Brilliant, Equally Confusing’

The speedy developments in GPT tech have computer scientists as well as non-IT society both enthused and worried.

“Today’s large language models are simultaneously unbelievably and unexpectedly brilliant—and equally confusing,” Cerf noted, adopting a comedic impression of the late founder of psychoanalysis, Austrian physician Sigmund Freud, who he admittedly resembles physically.

“Well, what we have now are ze artificial id und ze artificial ego,” Cerf joked. “What we are missing yet is ze artificial superego to control ze uncontrollable impulses of ze artificial id.”

The audience applauded roundly, appreciating both the humor and the sentiment. Out-of-control AI—and the perception of its potential harms—dominates headlines about the technology these days.

“Apart from the large-language models and the hallucinations they exhibit,” Cerf said, “is that they still show remarkable capability…We know there are some things it doesn’t do well. That should not distort your understanding and appreciation for what might be possible here at NIH when it comes to gathering large amounts of data, understanding correlations that are exhibited by that data and then looking for the causal model that will explain what those correlations are.”

In advance of his talk, NIH’ers posed approximately 115 questions via online polling. After about a quarter hour in lecture mode, the internet guru transitioned to a seat on stage for an open conversation with Bertagnolli, who was armed with five of the top-voted questions.

In Sickness and in Health

She led with a surprising true statement: “A major problem with health care is that actually very, very little of it is based upon rigorous clinical data.”

Photo: Leslie Kossoff

One of Bertagnolli’s major priorities as NIH director is to provide more evidence-based medical care and to make it available to more people. She asked Cerf how AI might help.

For starters, he recommended, health care providers might consider gathering data on people when they are healthy as well as when they are sick, in order to establish a baseline wellness factor.

“If I were a doctor and my patients only came in when they have symptoms or are sick, then all my statistics would say my patients are always sick,” Cerf pointed out. “One thing that is very important is to collect information about patients when they are not sick, so that I have some sense of what’s normal for them. That will help me figure out if and when they have gone on some excursion away from the norm. So, instrumenting ourselves might be very beneficial for ourselves as well as medicine in general.”

Huge Potential for Good

Other topics ranged from how AI can detect and weed out misinformation to ways the biomedical research community can better standardize its data for optimal sharing to Cerf’s advice for scientists just beginning their careers.

“I hope you realize what an opportunity NIH has to improve the state of health care not only here in the U.S. but elsewhere with the kind of research you’re doing and the attempt to exercise these powerful computing tools that are emergent,” Cerf concluded. “Generally something has happened over the last 20 years that I’ll call ‘computational X’ for every value of X you can think of—linguistics, chemistry, physics, economics—we are using computing tools increasingly to build models, test the models, to try to understand how the world works, to make predictions.

“NIH is invested heavily in trying to develop those kinds of tools,” he continued, “and you have the opportunity to make enormous progress, because you’re the source of fabulous research, great data and now the potential for using computer-based tools to make your predictions even more precise. If I were you, I’d be sitting here thinking, ‘Boy do we have a lot of work to do and a huge amount of opportunity to do good.’”

Photo: Leslie Kossoff

The event was popular NIH-wide. More than 700 people requested tickets for a venue that holds about 450. In addition to the in-person packed house, close to 1,800 people watched via NIH videocast livestream. View the recording at https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=54305.

The lecture is named in honor of Dr. Joseph “Ed” Rall, who helped define NIH’s modern Intramural Research Program and in the 1950s was instrumental in establishing an academic-like and culturally rich community within a government agency that was growing fast.

Since 1984, when Rall recommended adding a cultural talk to the NIH Director’s Lecture series, NIH has hosted such guests as opera singer Renée Fleming in 2019 to explore music and the mind, the Dalai Lama in 2014 to address the role of science in human healing, screen and stage icon Barbra Streisand in 2018 to discuss women’s heart health, and journalist Dr. Sanjay Gupta in 2015 to talk about medicine and the media.