Health as a Human Right

Galea Seeks to Widen the Dialogue

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

A sturdy building needs a strong foundation with numerous pillars to support it. The whole structure could be compromised if builders overlook proper materials and design.

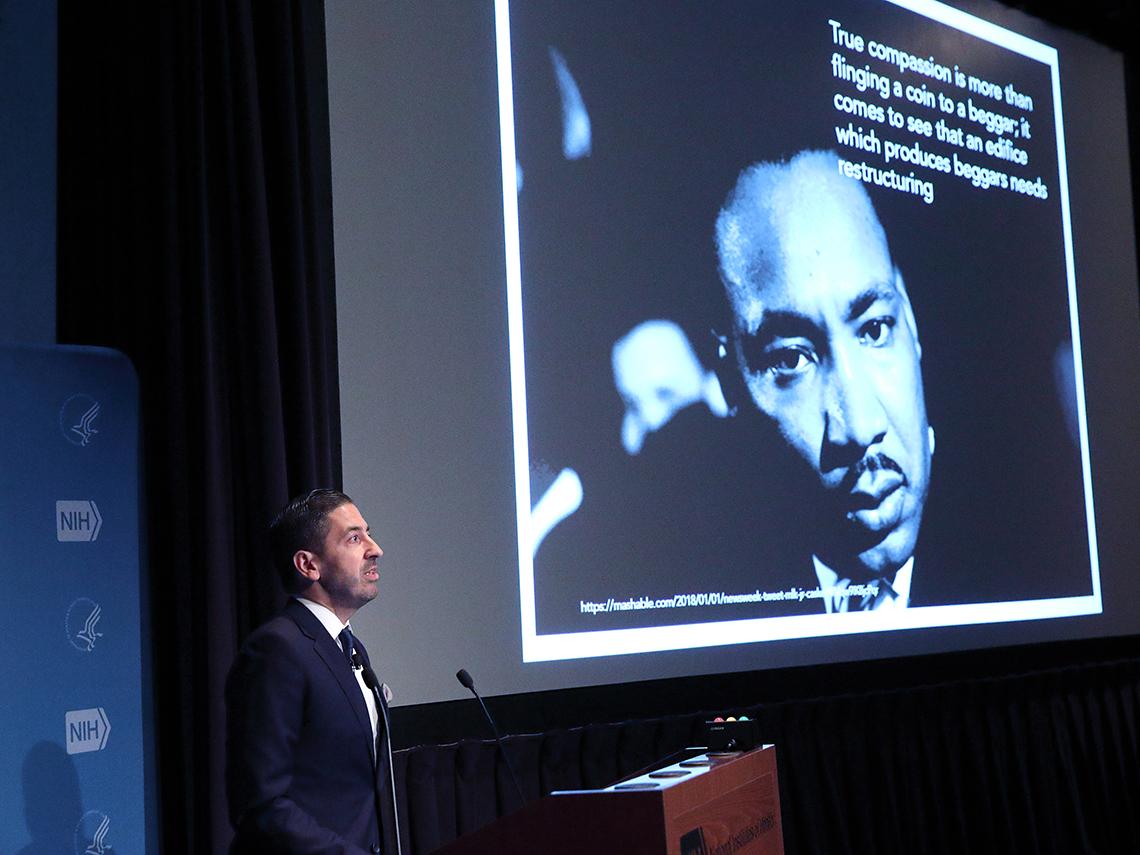

The same can be said for health, which can thrive from a supportive infrastructure. Strengthening our health requires addressing societal symptoms that weaken it, argued Dr. Sandro Galea, epidemiologist, dean and professor, Boston University School of Public Health. He delivered an impassioned talk at a recent NIMHD Director’s Series seminar in Lipsett Amphitheater.

“Ultimately, we cannot generate health without paying attention to the other forces that generate health outside the health care system,” said Galea.

These forces, he said, are encapsulated in the story of blues legend Blind Willie Johnson, who lived a century ago. Johnson, who grew up poor and black in the south, was blinded as a child in a domestic violence incident. In his 40s, he contracted malaria; the hospital refused to admit him and he died. The disease may have killed him, said Galea, but so did poverty, domestic violence, racism and poor access to health care.

The problem, Galea said, stems from “a mismatch between our spending on health and our health indicators.” U.S. health spending is much higher than in other developed nations, yet America fares worse on noncommunicable disease mortality and other health indicators across every age group.

Investing in measures to counter the forces that threaten health may seem utopian and unattainable, but the situation wasn’t always so dire, said Galea, and doesn’t have to be. Until the early 1980s, the United States ranked high among its peers in annual life expectancy. Today, the U.S. sits toward the bottom of that list, in its third consecutive year of declining life expectancy.

“It’s hard to think of any other sector where we are consistently outspending all our competitors, but getting less out of it,” Galea said.

The outspending is on medicine and health care, not on other health determinants such as socioeconomic conditions and access to care. Galea underscored that his views are not intended to diminish the importance of investing in health care and scientific research. He considers both pieces of a larger puzzle.

We might dismiss a disease outbreak across the world, for example, until that disease arrives in the U.S. Vaccine skepticism matters because it can create pockets of infection that spread, such as the recent measles outbreak in southwest Washington state.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

“Our health is collectively intertwined,” said Galea. “We will not be able to do anything to improve our health if we do not deal with the health of all.”

When health isn’t considered a public good, said Galea, we wind up with such incidents as polluted drinking water in Flint, Mich. Clean water should be a public good, he said, and health is something we all should own.

Politics sometimes drives health, said Galea, and it also presents opportunities to expand the national dialogue while pushing a healthy agenda. For example, since 1968, more Americans have been killed by firearms than all U.S. service men and women killed in all foreign wars combined. Traditionally, though, the gun rights lobby spends much more than the gun control lobby. The current national dialogue on gun violence, he said, was almost unimaginable a few years ago.

“It’s important to have humility to recognize that our lens with which we look at the world is fixed to a particular point in time,” said Galea. “Be part of the vanguard shifting these [ideas] forward.”

While the leading causes of death include heart disease, cancer, respiratory disease and stroke, the underlying causes may include tobacco, poor diet and microbial agents. Digging further, one can argue that underlying social causes such as poverty, low education and racial segregation also heighten morbidity and mortality, said Galea.

Furthermore, health should be a means, not an end. The goal should not just be treating people’s conditions, Galea said, but also keeping them healthier, longer.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Precision medicine is important, he said. “It’s [also] distracting us with it being an ever-targeted genetic molecular approach to fix [disease, while ignoring societal determinants].” Advances in discovery science are exciting and promising, he added, but let’s not get distracted from the larger picture. Rather than chase perpetuity, he said, let’s celebrate living.

The challenges are vast. With an open mind, we can change the lens and expand the conversation. Demand the conditions that generate better health for all, urged Galea. “Science is seldom enough,” he said. “Science has to be accompanied by a value set that promotes health.”

In a soccer game, concluded Galea, the net is huge, so the goalkeeper relies on the whole team to play good defense and keep the ball away from the net.

The goalkeeper, he said, is medicine, that cures us when we get sick. But we should invest in the other players so that we “promote health for everybody, making sure we have compassion to change the structures that generate health,” said Galea. “We need to make sure we pay attention to where we live, how we live, the air we breathe, the cities around us—that’s how we’re going to reverse the problem.”