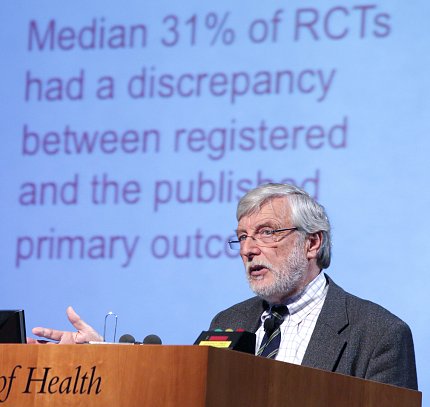

Much Biomedical Research Is Wasted, Argues Bracken

Photo: Bill Branson

As much as 87.5 percent of biomedical research may be wasteful and inefficient. So argued Dr. Michael Bracken at a recent Wednesday Afternoon Lecture in Masur Auditorium.

“Waste is more than just a waste of money and resources,” said Bracken, the Susan Dwight Bliss professor of epidemiology at Yale University School of Public Health. “It can actually be harmful to people’s health.”

For every 100 research projects, only half lead to published findings. Of those 50, half have significant design flaws, making their results unreliable. And of those 25, half are redundant or unnecessary because of previous work. “That’s how you get to 12.5 percent,” he said.

Researchers who publish novel findings are more likely to have produced exaggerated results or drawn incorrect conclusions. Many times, these early or “first” studies are based on limited evidence from small studies. When the experiments are reproduced in larger studies, Bracken said, the predictive value of the finding may decrease up to 90 percent of the time.

While replicating studies is necessary, there is sometimes waste in unnecessarily repeating studies. Repeating studies when there is already evidence suggesting a treatment is effective, for example, “means patients are being submitted to placebo when they can receive active therapy,” he noted.

Once several large-scale studies show a treatment is effective, he said, “you need an incredible amount of evidence to switch an estimated treatment effect from being protective to being even neutral, let alone a risk.”

Photo: Bill Branson

To reduce wasteful duplication, Bracken suggested researchers conduct systematic reviews for their research protocols. This is a type of literature review that involves systematically collecting and analyzing all of the relevant research papers. The goal is to summarize all the best currently available evidence. He advised scientists to conduct the reviews concurrently as research accumulates. Then, they would see if new studies are necessary in real-time. In human studies, he said, there are presently only some 408 systematic reviews published for every 10,000 publications.

Preclinical research, particularly in animal studies, is especially inefficient. Bracken said, for example, one of the cornerstones in clinical research—blinding investigators—is widely ignored in animal studies. Existing systematic reviews of animal studies show that very few studies are blinded or randomized. He believes animal study methodology is 40 years behind human clinical study design.

“There is never any justification for the use of animals or humans in poorly designed studies,” he said.

Bracken said there are strategies researchers can use to reduce the element of chance when designing studies. They can, for example, design larger studies based on more stringent statistical tests of the hypothesis. He says that the traditional 0.05 “p-value” has lost its ability to discriminate important research findings, especially when numerous comparisons are being made, and can produce results that are irreproducible and in some examples actually harmful to the public’s health.

P-values are used to determine the strength of an association. The smaller the p-value, the stronger the evidence, while the larger the p-value, the weaker the evidence. However, a p-value less than 5 percent “does not by any means indicate that the association is not a chance finding.”

Researchers should also be aware that many sources of bias are being underestimated in drawing conclusions from biomedical research in both preclinical and clinical research. Bracken believes scientists can substantially reduce bias if they are aware of it. “Reducing bias is usually not an issue of cost. It’s an issue of understanding where bias may come from,” he said.

Bracken applauded NIH for increasing its efforts to train young scientists on how to design and conduct experiments based on best practices.

Bracken believes many scientists are incorporating these kinds of changes into their research, but thinks there is still room for considerable improvement.