DNA Sequencing Beyond Earth’s Atmosphere

SpaceChat Checks In on Science in the ‘Final Frontier’

Photo: Ernie Branson

With one scientist planted firmly on planet Earth and another scientist in orbit 220 miles away on the International Space Station, NIH and NASA joined forces Oct. 18 for a live “SpaceChat” about DNA sequencing, the human genome and other topics related to conducting biomedical research in the “final frontier.”

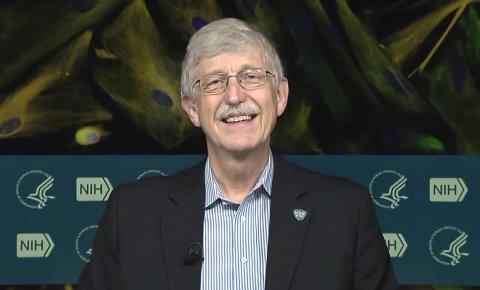

NIH director Dr. Francis Collins, on terra firma in a multimedia studio in the Clinical Center, talked for about 20 minutes with NASA astronaut and fellow DNA sequencer Dr. Kate Rubins, who is finishing a 4-month mission aboard the ISS. Their conversation—an extraterrestrial videoconference, if you will—occurred via satellite links between Mission Control Houston, NIH and the ISS.

The event, during which Collins posed queries to Rubins from viewers in real time and asked questions of his own, was carried on several social media outlets, including Facebook and Twitter.

Photo: Ernie Branson

“It’s been 13 years since I had the privilege of leading the Human Genome Project that read out that very first reference sequence of a human genome,” said Collins, “and now here we are ‘rocketing forward’ with lots of other advances that take advantage of our ability to read out DNA and RNA.”

In August, Rubins and her team made history. They sequenced DNA in space for the first time ever, using a portable biomolecule sequencer device that is about the size of a TV remote control. Scientists wanted to see whether such decoding of the human genome could be accomplished under microgravity conditions.

“This was truly an experiment in all senses of the word,” Rubins said. “We did not know if it was going to work the first time we were doing sequencing in space. Like every lab experiment, you put your pipetter down and you give it a try…It actually was a fantastic technology demonstration…We were able to show we can successfully do sequencing in space and we’ve sequenced over a billion base pairs at this point.”

Photo: Ernie Branson

The ability to sequence DNA in space opens a whole new world—quite literally—of opportunity for researchers, who hope one day to be able to identify organisms, diagnose diseases and detect potential health threats while outside Earth’s atmosphere. Rubins said the research also has implications for getting health advances and the latest medical technology to remote and underserved areas on this planet.

Beyond studies of the effects of weightlessness, “the radiation environment is the second major factor on the space station,” she pointed out.

“We just can’t simulate the low-Earth orbit environment on Earth,” Rubins explained. “The beams and accelerators that we have on Earth don’t give us the same mix of particles that are currently bombarding human physiology in low-Earth orbit. So, we can study that up here. We’ve had longstanding partnerships with NIH to understand what’s going on with cell physiology [in] orbit. And we can study this on the cellular level.”

Photo: Ernie Branson

The chat marked the first time NIH has teamed up on Facebook Live with the International Space Station.

“It worked well logistically,” noted the event’s chief organizer, Kim Seigfreid of NIH’s Office of Communications and Public Liaison. “NASA took our signal and the signal from the ISS and fed it to NASA TV. From there, the signal was pushed to FB Live.”

The chat garnered about 58,000 live views, with 225,200 additional views (and still growing), 1.8 million impressions on Facebook and more than 93,464,630 impressions on Twitter.

“We had viewers from all over the United States and more than 53 countries,” Seigfreid said. “The amount of viewers from other countries was the most surprising.”

Photo: Ernie Branson

Worldwide watchers included our closest neighbors Canada and Mexico as well as those farther afield such as Algeria, India, Pakistan, Turkey, Iceland, Vietnam, Kosovo, Taiwan, Tunisia, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Argentina, Tibet, Sudan and Kurdistan.

You can see the entire chat online at http://bit.ly/2ekYNo0.