Former HHS Secretary Devotes Life to Diversity

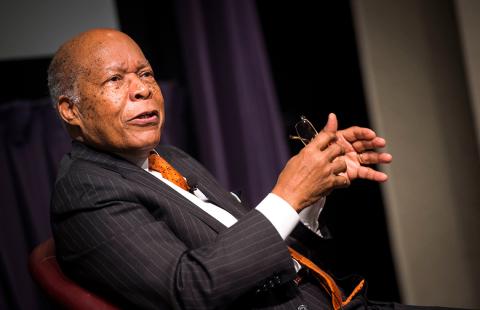

Photo: Lisa Helfert

Dr. Louis Wade Sullivan never forgot his roots. Throughout his distinguished career, the former HHS secretary, hematologist, professor and medical school president emeritus made great strides in health policy, medicine and education. Guided by his upbringing, Sullivan also made it his lifelong mission to bring inclusive diversity into our health system.

For Sullivan, life was an uphill battle, growing up a black man in the racially segregated rural south. Fortunately, he had a series of mentors and unexpected opportunities that set him on a path to success. Sullivan eloquently recounted his experiences—also told in his recently published memoir, Breaking Ground: My Life in Medicine—at an NLM History of Medicine lecture, Oct. 4 in Lipsett Amphitheater. In the casual town hall setting, the sizeable audience included quite a few fellow graduates of Sullivan’s alma mater, Morehouse College.

Sullivan’s story begins in Georgia in the 1930s. His father established the first black funeral home in rural Blakely. His mother commuted great distances to schools that would employ black teachers. Sullivan was fortunate to attend better schools in urban areas. His parents were his earliest role models, instilling in him a passion for education.

When it was time to see the doctor, rather than suffer the humiliation of the separate waiting room at the white doctors’ offices, Sullivan’s parents took him to see Dr. Joseph Griffin, the only black doctor in southwest Georgia, some 40 miles away.

“Dr. Griffin so impressed me that I decided, by age 5, I wanted to be a doctor,” said Sullivan.

He later found another role model in Dr. Benjamin Elijah Mays while studying at Morehouse College. “He was [always] telling us that in a segregated society, there may be barriers because of prejudice, but we should not have a barrier because of lack of preparation.”

Sullivan graduated from Morehouse in 1954, the year the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling declared school segregation unconstitutional. He then went to study at Boston University School of Medicine, his first experience living and working in a non-segregated environment. It was a positive one, he said, though he was the only black student in his class and 1 of only 3 at the whole medical school, at the time.

For his post-graduate training in 1958, Sullivan was stunned to get accepted to New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, which up until then had never had a black intern. The chair of medicine, a burly white physician from Tennessee, personally kept protective watch over him. “Then I saw my own prejudices,” Sullivan said. “I had made a judgment of him when I met him, with that southern accent.”

One of the most gratifying experiences of his professional career, he said, was presenting a research paper at the American Society for Clinical Investigation’s national meeting in 1963. His study linked heavy alcohol consumption with suppressed red blood cell production.

By 1973, Sullivan was a settled professor of medicine at Boston University, and married with three children, when Morehouse College recruited him to help establish a medical school in 1975. The Morehouse School of Medicine would become the only 4-year U.S. medical school organized for black students in the 20th century, joining Howard University School of Medicine and Meharry Medical College, which had been founded in the 19th century.

“The civil rights movement of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s opened the eyes of the country to just how severe the conditions were for blacks in the south,” said Sullivan. “So the country responded to that in a way that, when I started at Morehouse in 1975, not only were black physicians in Georgia supporting this medical school…but also the white physicians; they went with me when I had meetings with the governor or state legislature.”

In 1977, Sullivan was instrumental in founding the Association of Minority Health Professions Schools. “There was really an upwelling of support for activities around the country…to try and address the shortage of black and other minority physicians.”

Photo: Lisa Helfert

Today, minority physicians (blacks, Latinos and Native Americans combined) represent just 8 percent of our nation’s doctors, yet these minorities represent 32 percent of the nation’s population. Meanwhile, said Sullivan, a 2011 Science paper reported that first-time white investigators applying for RO1 grants from NIH had nearly double the success rate of equally qualified black investigators.

“We’ve made significant progress over the years in increasing the diversity of the health workforce,” said Sullivan, “but that progress has been far less than what we had expected.”

Advocacy is even more urgent today, he said, because “now we are more polarized as a society.” He cited the need for job training, career counseling and more scholarships for minorities.

“We need to strengthen K-12 education,” he said. “So many youngsters in inner cities don’t get the kind of academic exposure and counseling that they should. They don’t have role models.”

Another obstacle is student indebtedness. “We are not seeing students from low-income backgrounds coming into the health professions,” Sullivan said. “Those who do come through end up with significant debt…that drives them into high-paying specialties or into affluent communities.”

In 1989, President George H.W. Bush appointed Sullivan secretary of HHS, where he would develop several initiatives to increase racial, ethnic and gender diversity. He oversaw the formation of NIH’s Office of Minority Health, later to become NIMHD. He also oversaw the appointment of NIH’s first female director, the late Dr. Bernadine Healy, as well as the first female and Hispanic surgeon general and first female HHS chief of staff.

One important feat under his leadership was getting new labeling on packaged foods to help Americans make healthier choices. Sullivan recounted the arduous process of negotiating the FDA food labeling, which the Department of Agriculture opposed over concerns it would hurt the sales of dairy farmers, the cattle industry and other constituents. When President Bush said he’d arbitrate, Sullivan came equipped with a McDonald’s placemat that featured a nutrition label to illustrate his point. Why would a fast-food giant list a food label if it would hurt sales? “Then I knew I had him,” Sullivan said. Within days, the President accepted his recommendation.

After his HHS term, Sullivan returned to Morehouse School of Medicine as its president. The medical school’s notable graduates include former surgeon general Dr. Regina Benjamin, Meharry College president Dr. Wayne Riley and Dr. Sam Gulube, a South African doctor who returned to his country to found its first nationwide blood banking system.

“From my perspective, one of the most important measures of an institution is what do its graduates do,” said Sullivan. “Do they change the world?” Sullivan is yet another distinguished Morehouse College alumnus, continuing that tradition.