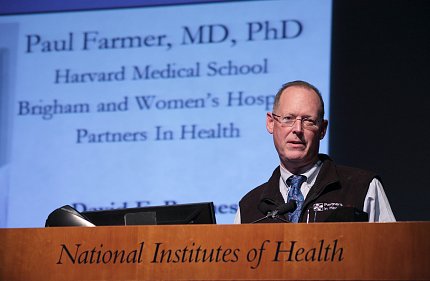

Physician Gives Hope, Healing To World’s Poor

Photo: Bill Branson

Dr. Paul Farmer has spent decades providing medical care and expanding health access to the world’s poor, shattering the myth that it’s untenable to treat the sick in settings of privation. Treating underserved populations is not a pipe dream, Farmer said, when you have “the staff, stuff, space and systems” to make it a reality.

When Farmer last spoke at NIH 7 years ago, he showed a blueprint for a modern hospital in central Haiti. Many skeptics thought it would never get built. When he recently delivered the annual NIDCR/FIC David E. Barmes Global Health Lecture to a packed Masur Auditorium, he proudly showed a photo of University Hospital, the largest solar-powered hospital in the developing world. It was built by Partners In Health, the nonprofit he co-founded 30 years ago in central Haiti, which now works in 10 countries around the world.

“When you have the staff, stuff, space and systems you need, not only can you do better research, you can actually make a great difference in people’s lives,” said Farmer, Kolokotrones university professor at Harvard University; chair of the department of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School; and chief of the division of global health equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Farmer’s interest in Haiti and helping the poor began as a child. Raised in a Florida trailer park, and once living in an abandoned school bus, Farmer grew up picking fruit with Haitian migrant workers. He later met and interviewed more migrant workers on tobacco plantations near Duke University, where he studied medical anthropology on scholarship. Then, as a doctoral student at Harvard, between labs and exams, he began visiting public health clinics in Haiti.

Photo: Bill Branson

“We live in communities; we’re connected across borders,” said Farmer, who advocates for global health equity. His prescription for achieving health equity is combining research and training with care. “You can’t conduct research on sick people without taking care of them. You can’t train clinicians, doctors and nurses without having the chance to take care of the sick,” he said. “Medical reform links these three things—research, teaching and service—together and that’s what’s right about an American teaching hospital.”

Unfortunately, when the U.S. responded to the most recent Ebola epidemic in West Africa, he said, much of the funding went toward containment, not toward care. “Containment without care has been the MO [modus operandi] of all medical activity in that part of West Africa since the late 19th century…95 percent of all the deaths were right there.” Countless lives could’ve been saved, he said, if these countries had a health care system. He thanked NIH for taking risks and doing its share in the midst of that health crisis.

“Pandemic disease has been our fate for centuries and will remain our fate,” said Farmer. “I don’t believe the reason that NIH, and NIAID particularly, invested in Ebola was just because they were frightened it would be used as a bioweapon…This is science. This is a pathogen that afflicts people, and non-human primates as well, and that’s reason enough.”

In West Africa, 70 percent of Ebola patients died while nearly all Americans, with proper care, survived. Why? West Africa lacked the staff, stuff, space and systems to care for Ebola patients. Many who died were poor, said Farmer, and many others were middle-class health professionals—more than 200 just in Sierra Leone—and family caregivers.

When Partners In Health arrived in Port Loko, not far from Sierra Leone’s capital, Freetown, they were set up in an abandoned vocational school with no walls, electricity or running water. In Liberia, nine of the 11 facilities built with support from the U.S. military never cared for a single Ebola patient. Farmer notes, “Local capacity-building has to be linked to actually taking care of people.”

Over the years, some diseases seem to come from obscurity and cross the globe. One such disease is HIV/AIDS. While an infectious diseases fellow in the 1990s, Farmer often heard: Is it sustainable to give people antiretroviral therapy in Africa? The question always frustrated him.

“Think about the absurdity of trying to use the word sustainability as a diagnosis to decide whether that person should receive the only treatments we have for a particular lethal infection or one that causes great suffering,” said Farmer. Is it fair to tell someone—anyone—it’s not cost-effective to provide you with medicine? It’s unsustainable, he said, to argue against treating those with fewer resources.

Photo: Bill Branson

In the 1990s, Haiti had the highest prevalence of HIV in the western hemisphere. More than 280,000 Haitians were living with HIV and some 30,000 adults and children died of AIDS. At a time when many in the U.S. government believed it too expensive and complicated to treat those infected in the developing world, PEPFAR (the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief) would become the largest program for global HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care.

“About 15 million people are alive today because of PEPFAR,” said Farmer. “It doesn’t solve all problems…but it sure solved a lot of problems for those 15 million people.”

The morning of Farmer’s lecture, a young Rwandan who works at NIH told Farmer that his district in Rwanda has not experienced a single case of mother-child HIV transmission for at least 3 years. “That’s the fruit of science,” exclaimed Farmer. “That’s the kind of effect we can have when we link knowledge that comes out of basic science to clinical trials to an equity platform.”

Another new source of pride for Farmer and Partners In Health is the launch of the University of Global Health Equity in Rwanda.

“In so many places in the world, there’s everything left to do,” Farmer said. “Everyone can find a way to put equity in their agenda.”