Astronaut Describes Experiences Aboard ISS, Sequencing DNA in Space

Photo: Andrew Propp

If it weren’t for an NIH grant application, NASA astronaut and biologist Dr. Kate Rubins would never have been the first person to sequence DNA in space.

“I was writing an R01 [grant application] when my friend called me and said there are astronaut applications online,” she recounted during a talk at Masur Auditorium on Apr. 25. “And it turned out to be an excellent procrastination tool for grant writing.”

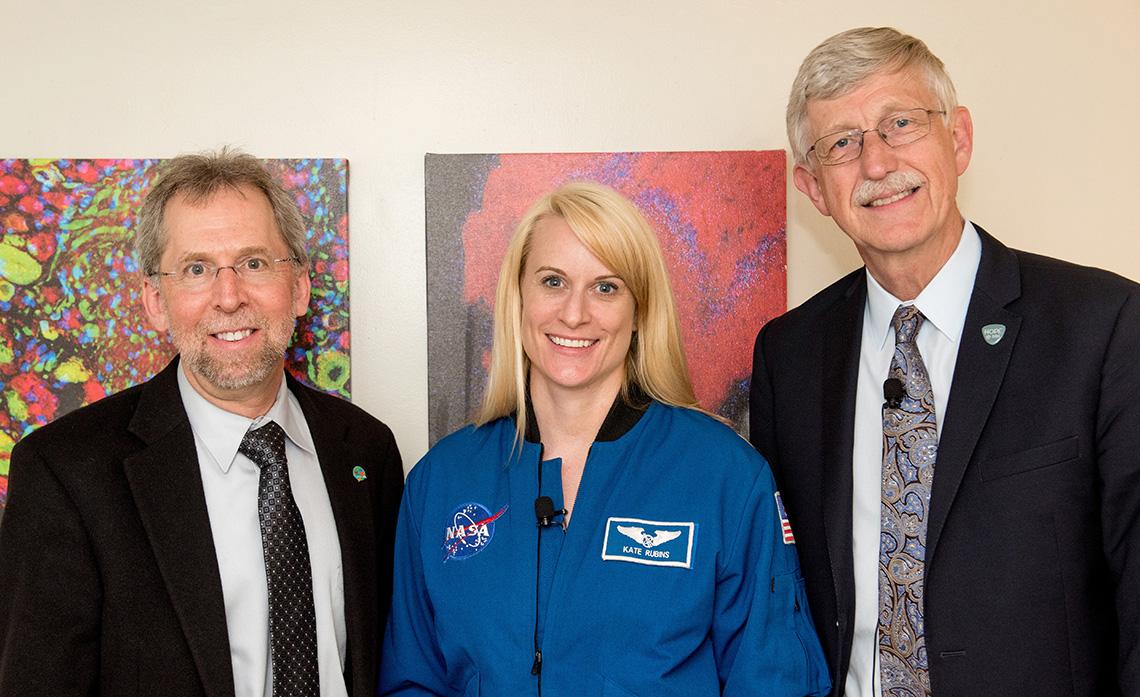

She spoke about her 115-day stay aboard the International Space Station (ISS). NIH director Dr. Francis Collins then joined her on stage for a conversation that was beamed universe-wide to whoever’s out there on NIH’s Facebook page. This was their second conversation; the first was last Oct. 18, when the two conducted a “space chat” as Rubins orbited 220 miles above Earth.

Rubins’ visit to NIH was part of National DNA Day, which commemorates the successful completion of the Human Genome Project and the discovery of DNA’s double helix.

Photo: Andrew Propp

She said the purpose of conducting research aboard the station is to learn about fundamental differences in both physical and biological processes in microgravity, the effects of radiation and the vacuum of space. These conditions allow researchers to conduct experiments in environments that cannot be replicated on Earth.

During her stay aboard the ISS, Rubins demonstrated for the first time that it’s possible to sequence DNA in space. One of the reasons for conducting the experiment was to figure out a way to identify microorganisms living on the ISS in real time. This technology might give researchers an opportunity to diagnose diseases, detect potential health threats rapidly, and, perhaps one day, identify unknown DNA-based life forms on other planets.

Her lab featured a small sequencer the size of a TV remote control and a tablet computer. She sequenced mouse, viral and bacterial DNA. The genetic material was prepared in a lab on Earth and sent up in a separate cargo ship.

Before she proved that sequencing can be done in space, there were a few concerns about the experiment. First, fluids behave differently in space. Air bubbles, for example, can form within air bubbles.

“Everything and anything you’ve ever understood about fluid behavior changes when you don’t have the force of gravity influencing that fluid,” she explained.

There were also concerns about whether the samples would survive the launch and journey to the ISS and whether the results of the experiment would be similar if the sequencing were conducted on Earth. The samples arrived intact and the experiments conducted on Earth yielded similar results.

Photo: Andrew Propp

Before she could fetch the sequencer, Rubins and another astronaut conducted two spacewalks.

On the first, they installed an international docking adapter outside the station, which will allow commercial spacecraft to dock at the ISS. On the second walk, the astronauts retracted a thermal radiator and installed high-definition cameras.

“It’s incredibly challenging to do a spacewalk. You’re free floating, you’re moving around in all six dimensions and your tools are floating,” she explained. “Even the most trivial tasks require an insane amount of focus, detail and attention.”

After she spoke, Collins came on stage to read Rubins questions submitted by NIH staff and online viewers. The Facebook broadcast had 108,000 live views.

When asked what’s preventing astronauts from exploring deeper into space to planets like Mars, she responded, “We need to protect astronauts from radiation.” Rubins explained that NASA continues to study how long-term weightlessness affects vestibular, bone and muscle health.

“These are questions that are within our ability to answer within the next 10 years or so,” she said. “There are no show-stoppers that are absolutely going to prevent us from going to Mars.”

Collins then asked her for advice on how to get children involved in science. She encouraged students to begin experimenting early.

Photo: Andrew Propp

“Biological experiments are a great way to get students interested, you know, thinking about their microbiome and the microbial world around them, thinking about physiology,” she said. “All of these things are accessible to kids that are really young.”

Rubins knew she wanted to be a scientist when she was 15. At that age, she attended a conference on recombinant DNA where she discovered scientists could interpret and potentially change the genome. That experience shaped what she studied in school.

One online viewer asked about her favorite thing in space. She responded that “being able to see the Earth from space was the most incredible thing.”

During her spacewalk, she was above the coast of North Africa. Viewing the bright Sahara desert set against the stark blue of the ocean through “only your visor is this incredible sight,” she marveled.

As for what’s next, Rubins said she’s learned to go with the flow. “The driving force is to always have interesting questions to ask,” but “I guarantee you I’ll be doing something scientific.”