Rall Lecture

Fleming Discusses Healing Powers of Music

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

The debate over whether music is a product of cultural invention, like writing, or of biological evolution, like speech, has divided scientists and other thinkers since Darwin’s time. Everyone must have experienced the mood-uplifting and optimism-inducing effects of music at some point in their lives, but few of us know of the extraordinary healing powers that music can have on diseases and disabilities.

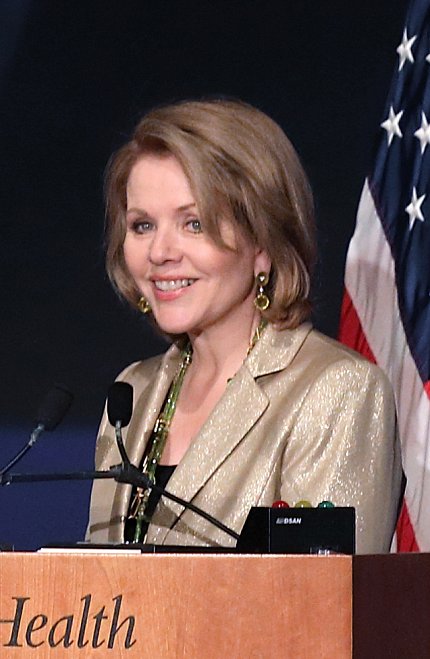

To explore these powers, NIH invited renowned opera singer and Grammy and National Medal of Arts winner Renée Fleming to give the annual J. Edward Rall Cultural Lecture on May 13. As a musician and participant in NIH research on the relationship of music to brain activity, Fleming shared her perspectives on how music influences well-being.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

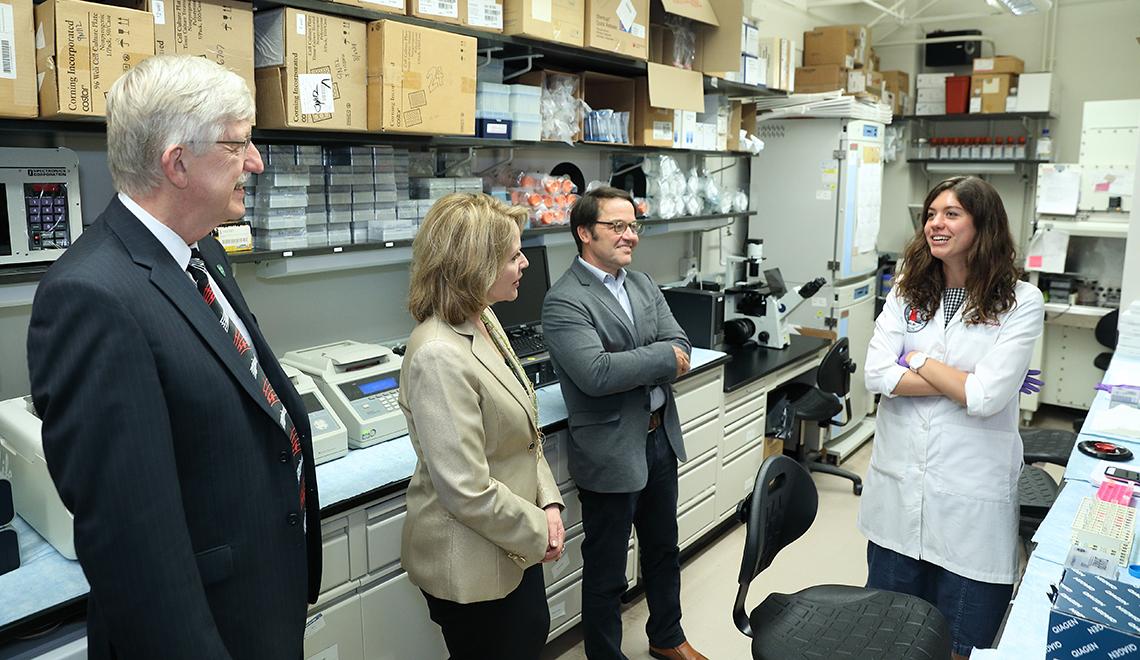

The “Sound Health: Music and the Mind” initiative, a partnership of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and NIH, in association with the National Endowment for the Arts, was born during a fortuitous meeting of Fleming and NIH director Dr. Francis Collins at a dinner party in 2015. At the time, Fleming had just begun serving as artistic advisor to the Kennedy Center. Familiar with the underpinnings of mind-body connection, she subsequently proposed the idea of studying the interaction of music and neuroscience to Collins, who enthusiastically embraced the idea.

The Sound Health initiative kicked off in January 2017 with a workshop including musicians and scientists at NIH. An NIH-wide working group on music and the brain was formed, and after careful deliberation of the research opportunities, announced the availability of $5 million in additional funding to explore the neuroscience of music.

Fleming discussed the positive effects of music on psychology, child development, brain activity and aging, while providing examples of research in these areas.

Her presentation started with the introduction of the bone flute, the earliest musical instrument, invented 40,000 years ago. Fleming believes that music predates speech and has been entwined with human life in every civilization and culture. The fact that the human auditory cortex has a separate area for interpreting musical tones (a “music room”) is consistent with longstanding benefits of music in human evolution.

Studies have shown that exposure to music and rhythm from an early age helps children develop language, reading and comprehension skills, memory and focus, compared to a control group with no exposure to music. The observations align with visible differences in neurological structures in the two groups. “Researcher Kenneth Elpus, right here at the University of Maryland, has shown statistically that music and arts programs enhance creativity, reduce dropout rates and lead to higher achievement,” Fleming said.

Music helps humans connect and bond with one another. It strengthens communities, as we typically see during social gatherings such as weddings and political rallies. “Music impacts brain circuits involved in empathy, trust and cooperation,” Fleming said as she introduced the audience to an experiment by Dr. Laurel Trainor that demonstrated rhythm-induced cooperative behavior in infants.

Cerebral activities such as singing, speaking or even processing musical notes profoundly affect brain activity. Fleming recalled her time inside an MRI scanner at NIH in April 2017, when she volunteered for a study under the Sound Health initiative to find out how her brain fired differently while she sang, spoke or imagined singing. It was imagining singing that inspired the greatest brain activity—perhaps because it was such an unfamiliar behavior for this internationally known singer.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

In a remarkable experiment by Dr. Charles Limb, jazz pianist Matthew Whitaker’s visual cortex became highly active under the MRI scanner while he was improvising jazz on a special metal-free keyboard that could be safely included in the MRI room. Whitaker was born blind and therefore his visual cortex had little to do with seeing. “This shows our brain’s remarkable plasticity, its ability to rewire itself,” Fleming said.

Use of music to soothe weary souls has been in practice from Plato’s time, some two millennia ago, to modern times, where it is applied to comfort war veterans living with PTSD and injury. Fleming noted that “music memory is often the last to go in adults with dementia,” signifying the cohesion music brings to a brain in progressive disintegration.

Forrest Allen, who suffered a horrendous traumatic brain injury after a snowboarding accident, was never going to speak again, according to his doctors. When the prospect of his recovery looked bleak, an innovative music therapist was called in. The audience watched enthralled as Allen, completely recovered today, and now a student at George Mason University, spoke to the camera saying, “Music got me here.”

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

In an age of loneliness where everybody is connected by the internet but nonetheless suffers a mass disconnect socially, Fleming feels that we are fortunate to have more than 100,000 performing arts organizations in the U.S. “The arts humanize us and bind us to each other and our children,” she said in closing remarks.

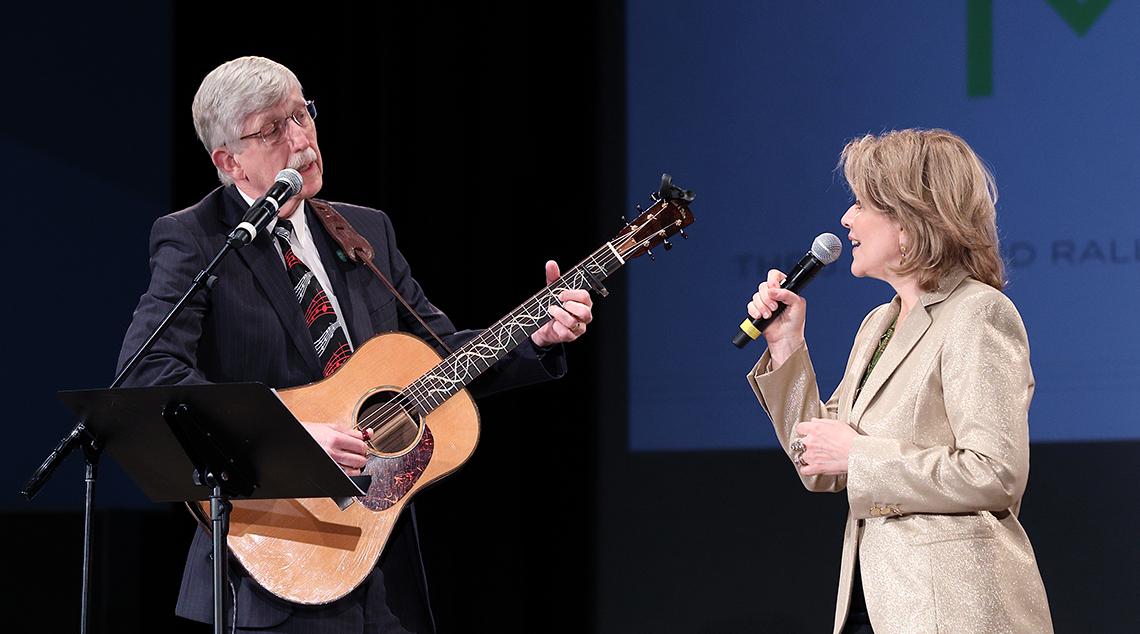

After the talk, Collins and Fleming engaged in a Q&A session, where Fleming talked about growing up in a family of musicians, grappling with stage fright as a performer and how she has to work hard to control her emotions when singing in settings of mourning, as in a performance for families of 9/11 victims or at the recent funeral of Sen. John McCain.

The two also talked about how music therapy is likely to enter mainstream disease management and hoped that it would be covered by medical insurance in the future.

The lecture ended with their duet rendition of Leonard Cohen’s anthem Hallelujah, followed by the 1864 hymn How Can I Keep From Singing. You can watch those musical contributions at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpuQ65ESq4c.