At Roberts Lecture

NIMH’s Berman Discusses Williams Syndrome

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

In an engaging video, the interaction between two young children is shown. One child is clearly much more social than the other. She continuously tries to interact with the other child, who is seen shying away. Dr. Karen F. Berman, senior investigator and chief of NIMH’s Clinical and Translational Neuroscience Branch, said that the opposite behavior pattern was the work of gene dosage.

Berman was the guest speaker at the annual Distinguished Women Scientists at NIH lecture series, held recently in memory of NIH scientist and mentor Dr. Anita B. Roberts.

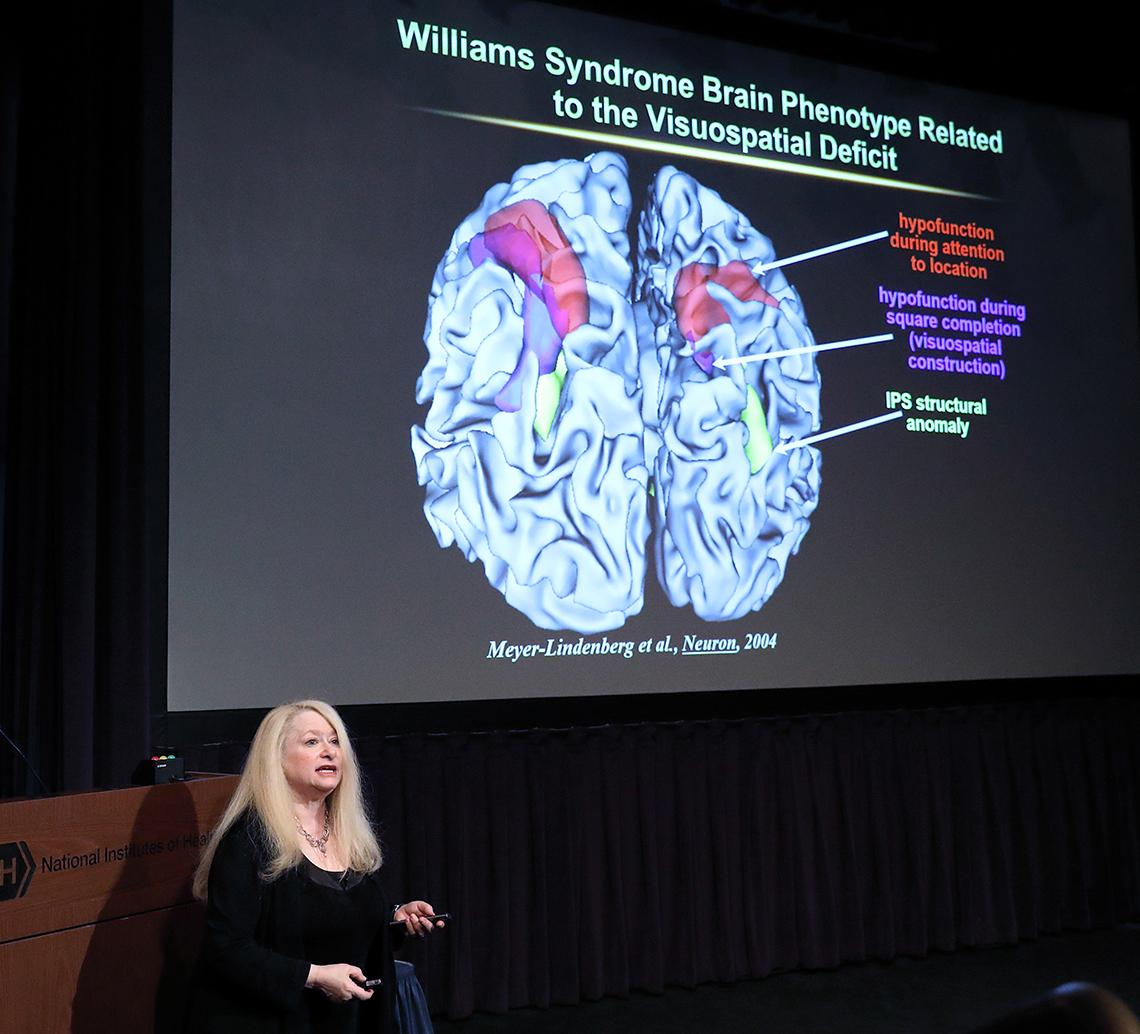

Berman and her colleagues used functional MRI to take pictures of brain regions in individuals with Williams syndrome (WS), caused by deletion of the 7q11.23 locus in one of the two chromosome 7s (hemi-deletion). In people with WS, “the behavioral features that are distinctive are good language and face recognition but severe problems with visual-spatial construction,” Berman said, describing the cognitive profile of individuals with WS. Berman’s group identified the intra-parietal sulcus region of the brain in WS as associated with these cognitive traits.

“Since we published this, it has probably been one of the most well-replicated and reliable brain phenotypes that has been reported in Williams syndrome,” Berman said. “For us, that means that it is a great brain phenotype for mapping gene effects,” she added, discussing how her group identified genes responsible for WS-specific cognitive traits.

The gene for lim kinase 1 (LIMK1) appears to be associated with cognitive phenotypes in WS. “We found that people with this gene hemi-deleted had visual-spatial construction impairments and reduced intra-parietal sulcus gray matter and neuro-activation, similar to those findings in WS,” Berman said, stressing that they were particularly interested in LIMK1 because it is important in neuron maturation and migration.

Her group subsequently saw, in a large cohort of healthy individuals, that variations in the LIMK1 gene sequence were associated with grey matter volume changes in the same regions of the brain as those affected in WS. Furthermore, neural communication between dorsal and ventral visual streams in the brain also varied as a function of LIMK1 sequence differences in the gene. “What’s remarkable here is that both the structural and functional differences occur in the same direction, according to LIMK1 haplotype,” Berman concluded.

In addition to their distinctive cognitive profile, individuals with WS have high sociability. They are socially fearless from infancy but have anxiety in non-social environments. In a short video, a child with WS shows no separation anxiety (on being away from her mom) when she interacts with a boy she doesn’t know. “People with WS score as highly gregarious, people-oriented, tense, sensitive and visible on a well-validated personality questionnaire,” Berman said. Her group found that the insula region of the brain is associated with personality traits in WS.

The gene GTF2I, which is located toward the end of the 7q11.23 genetic locus, was found to be specifically associated with insula volume in studies by Berman’s group. Therefore, the GTF2I gene and the insula region are responsible for behavioral aspects of WS, analogous to the LIMK1 gene and the intra-parietal sulcus region, which are responsible for the cognitive aspects.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

“GTF2I, like LIMK1, is a very interesting protein and gene…It binds to promoter regions of various genes and could influence a variety of genetic pathways,” Berman said. Mouse pups with an extra copy of the GTF2I gene showed increased separation anxiety in a study by extramural colleagues. Conversely, deletion of one copy of this gene caused decreased separation anxiety, reflecting human behavior in WS. Additionally, “Variation in this very same gene is important not only in the transition of wolves to domestic dogs, it is also related to how friendly current dog species are,” Berman noted, describing the findings of a study by an NHGRI team.

Individuals with a duplicated 7q11.23 locus have a number of cognitive and behavior traits that contrast with those seen in people with WS. The former suffer from social and separation anxiety, but they are adept at visual-spatial construction.

Closing her talk, Berman described how copy number variation at the 7q11.23 locus is a great example of gene dosage directing stepwise phenotypic changes. This and similar work can help in our understanding of how genes work through the brain to influence complex human behaviors and disorders, she concluded.