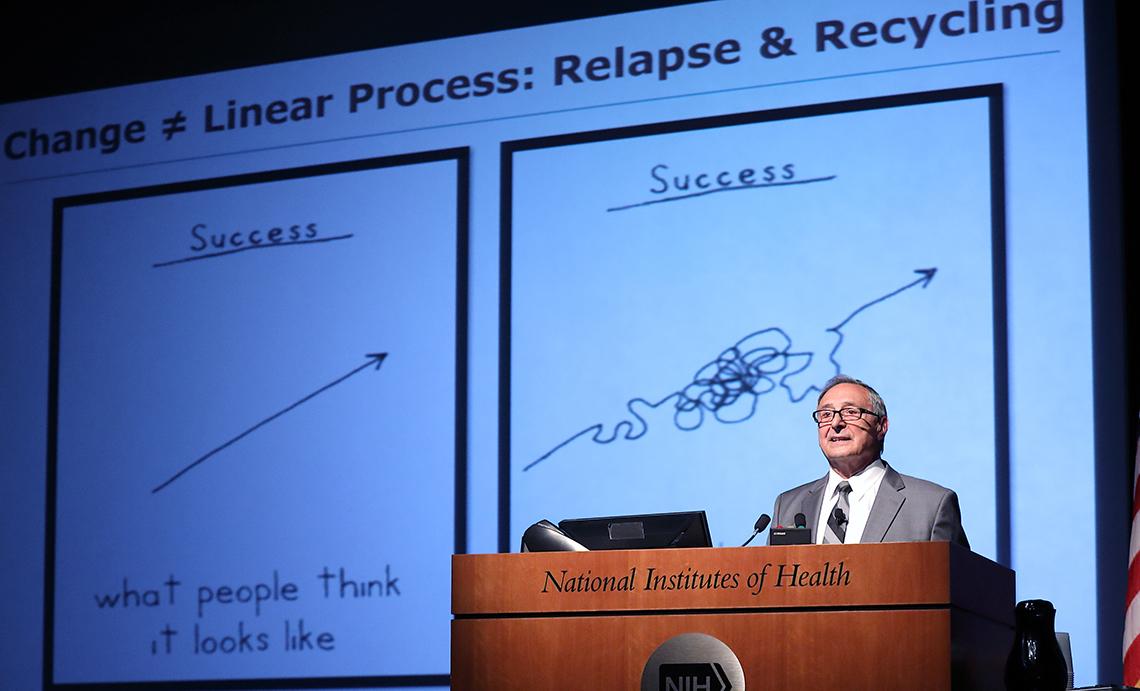

‘A Messy Process’

DiClemente Advocates Rethinking the Road to Recovery

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

It’s inevitable. Everyone makes mistakes. A turning point comes when we learn from them. Trying again, perhaps a bit differently this time, could have life-changing effects.

For people in treatment for alcohol use disorder, a relapse—a drink or series of drinks after committing to abstain—can be demoralizing. That’s why Dr. Carlo DiClemente, professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, wants to dispense with the term “relapse” or at least think differently about how it’s characterized.

Relapse is a label that stigmatizes, blames and contributes to failure, said DiClemente, who currently is director of UMBC’s MDQuit Resource Center. He spoke at NIAAA’s 11th annual Jack Mendelson Honorary Lecture recently in Masur Auditorium. In many cases, he said, a relapse is a useful, sometimes necessary, event toward sustained change.

Relapse should not be defined by the number of drinks or consequences but should incorporate the person’s resolve. “You have to have had at least a period of abstinence or change for you to have a relapse,” said DiClemente.

“Relapse only [happens] when the individual gives up on making the change,” he said. “If someone is still struggling to make a change or take control of their alcohol or stay abstinent, they’re not relapsing. They’re in the process of struggling to take action and do maintenance activities that would help them get into, and stay in, recovery.”

Multiple large-scale alcohol treatment studies over five decades confirm a consistent trend: there’s a lot of relapse. The studies revealed that only a small percentage of participants completely abstained for an entire year following treatment. Many were still drinkers, and some remained high-risk drinkers. The results have led DiClemente to purport that the notion of relapse contributes to fatalistic attitudes and failure identities.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

If a relapse makes people think they’ve failed, they may abandon their efforts altogether rather than forging ahead to overcome their addiction. Acknowledging that some people need medication during recovery, DiClemente continues to promote a cognitive/behavioral model, namely one he co-created more than 30 years ago that’s still in use today.

Such setbacks are not unique to addiction. “Relapse is actually probable with any health behavior change, and it’s often at the same rates as with addictive behaviors,” said DiClemente. From sticking to dietary restrictions to faithfully taking medication for chronic illness, it’s tough to avoid slip-ups when trying to sustain behavior change over time.

This approach, the transtheoretical model (TTM), features five stages of behavior change, each of which identifies critical tasks needed to move to the next stage. “Relapse is a problem of adequately completing one or more of the critical tasks of the stages of change that would enable someone to achieve sustained change,” he said.

The first stage is precontemplation (not interested or ready to consider change). Then the person considers change in the contemplation stage, by weighing risks and rewards. The preparation stage brings commitment and planning begins. The fourth stage is action, during which the person implements and revises the plan as needed. Finally, in maintenance, the person consolidates the change into a new lifestyle.

Photo: Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

The process may seem straightforward, but it’s multifaceted. “Just because somebody moves forward and starts thinking about change doesn’t mean they’re going to stay there” and move to the action stage. “It’s a messy process,” said DiClemente, noting that there are many ways recovery can be compromised.

In the TTM, relapse is not a stage but rather an event that triggers recycling, or a slipping back to an earlier, pre-action stage. Regression, relapse and recycling to earlier stages happen throughout the journey to recovery, and relapse typically occurs in the action stage.

“Slips and lapses teach us there’s something wrong with what I’m doing currently,” he said. If someone is recycling repeatedly and not revising the plan, it becomes a redo that isn’t working; clinicians should assess whether environmental, medical or other factors are impeding progress.

There will always be high-risk situations that make people vulnerable to relapse: cravings, temptations, social cues and stress among them, but they are not completely responsible for relapse. “Recycling helps people learn how to get all the different parts of the process done adequately,” said DiClemente.

As the saying goes, where there’s a will, there’s a way. Some of the best predictors of success in alcohol recovery are coping skills, commitment, sound decision-making and reduced temptation mixed in with a healthy dose of confidence.

Most people who are addicted recycle through multiple quit attempts and interventions, said DiClemente. “You really want to know: where are you now [on the stages continuum], not did you relapse?”

Consider relapse to be a temporary setback and a learning opportunity on the way to getting well, said DiClemente. Consider it recycling on the road to recovery.