View from Outbreak Origins

NIAID’s Lane Discusses WHO COVID-19 Mission to China

Dr. Cliff Lane was at Dulles International Airport waiting in line to board a flight to Tokyo when he got an urgent email. A World Health Organization mission to China—where the novel coronavirus outbreak was first discovered—had just been approved and Lane’s appointment as a member of the WHO team needed to start immediately. How soon could he get to Beijing?

It was Feb. 13, a little more than 6 weeks since coronavirus infection in Wuhan, China, had led to the first cases of a serious respiratory illness now called COVID-19. Lane was already headed to a coronavirus trouble spot—a cruise ship docked at a port in Yokohama, Japan’s second largest city. Rates of infection and illness were rising fast on board and a call had gone out to the international medical community. Was there anything NIH could do to accelerate a research response in the area of therapeutics? Remdesivir, a novel antiviral drug that had been studied in the recent Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), was being floated as a potential treatment. That’s where Lane’s head was too, even as he heard the boarding announcement for his flight.

“It wasn’t even on my radar that I would be selected [for China],” he recalled, “because I knew that there were only a few people going.”

Of course, after 41 years at NIH, Lane, NIAID’s deputy director for clinical research and special projects, is no stranger to deadly pathogens. About 6 years ago, he was among the beaming NIH’ers waving a very public farewell to Nina Pham, a nurse and patient with Ebola successfully treated in the Clinical Research Center’s new special clinical studies unit, which was established to conduct research on an emerging infectious disease.

“This goes back to SARS [severe acute respiratory syndrome],” said Lane, detailing some of NIH’s recent history with novel infections. “SARS was the first outbreak for which we developed a Clinical Center protocol. There’s a coronavirus that causes SARS and a coronavirus that causes MERS [Middle East respiratory syndrome]. There are also coronaviruses that cause the common cold. Ever since SARS [in 2003], NIAID has had a clinical research program on coronaviruses. We have been able to jumpstart some of the current research from that basis.”

Over the past decade, Lane’s group has conducted several clinical trials on Ebola virus here and in parts of West Africa such as Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. Currently, a study is underway in the DRC. He was also on the front lines of HIV research back in the early days of the AIDS epidemic. The WHO summons to China, too, represented an incredible opportunity to experience and learn virtually at a disease’s Ground Zero. But first, there was Tokyo.

“I really felt I had an obligation to the Japanese government,” Lane said. “Our relationships with other governments are important and we needed to honor that…So I’m basically [during] the entire flight to Tokyo working through all the different time zones trying to line up all the things that needed to be done.

“Getting a visa to China is a challenge in calm, usual situations,” he continued. “Doing something like that in an emergency takes an enormous amount of coordination. It was WHO pitching in. It was NIH pitching in. It was the State Department, including the U.S. embassies in China and Japan, the WHO and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in China all helping. It was an amazing number of entities working together. By the time I landed in Japan, I headed straight to the Chinese Embassy in Japan to get a visa to China. That was remarkable in itself.”

The WHO-China Joint Mission on COVID-19 had one overall goal: “To rapidly inform national (China) and international planning on next steps in the response to the ongoing outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and on next steps in readiness and preparedness for geographic areas not yet affected,” according to the mission’s report.

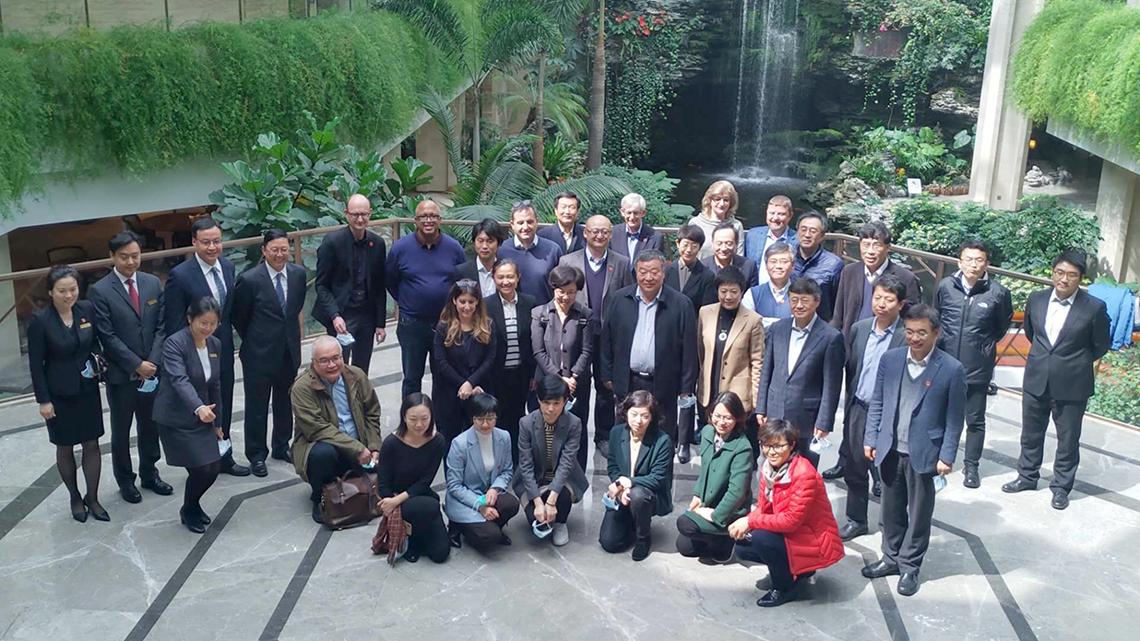

Twenty-five members formed the group—half from China and half representing WHO. The WHO group included experts from several countries including Canada, Germany, Japan, Nigeria, Russia, Singapore and South Korea. Lane, on his first official WHO assignment, was one of two Americans.

“It was a really good group of people to work with,” he said. “[WHO] tried to select people from different geographic areas as well as a diversity of skill sets. I was there representing the research response. Others represented epidemiology, infection control and diagnostics. The diagnostics person was from Russia.”

The mission took about 9 days (tack on 3 extra for Lane, who rerouted himself from Japan prior to his WHO role). The WHO delegation traveled from Beijing to Shenzhen, Guangdong, and from there to Guangzhou. The group had briefings by political leaders, hospitals, community centers and China’s equivalent of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at the national, provincial and municipal levels.

A smaller mission contingent that didn’t include Lane visited Wuhan, epicenter of COVID-19. He was temperature-screened at each airport in Japan and China, and for safety’s sake, he self-quarantined for 2 weeks after coming home.

He shared notable observations from his travels.

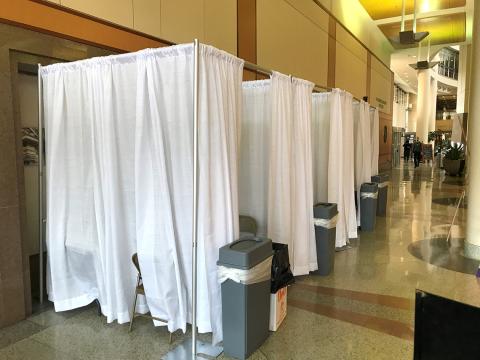

“The first thing I noticed at the boarding gate to the flight to China is that everybody’s wearing a mask except me,” he said. He noted the same thing on the bus from the airport to the hotel and was not allowed into his hotel without one. He was given a mask at the hotel entry’s fever checkpoint before being allowed to go to the reception desk to check in.

“The Chinese were managing this in a very structured, organized way,” he explained. “When we got there, the outbreak was already coming under control in China. The measures they put in place appeared to be working—I think they felt there were lessons learned they wanted to share with the rest of the world. It demonstrated their successful response and I think they felt a fair degree of pride in what they had done…From what I saw in China, we may have to go to as extreme a degree of social distancing to help bring our outbreak under control.”

The world has experienced and endured pandemics before, so what makes COVID-19 unique?

For one thing, Lane explained, it is caused by a new virus and thus we are not entirely sure what to expect. “Typically, when we think of a respiratory virus, we think common cold, flu, MERS and SARS. The clinical syndrome of [COVID-19] is somewhere in that spectrum, but where it fits—in terms of its transmissibility, its pathogenicity or lethality—that’s all being learned on the fly,” he said. “It is a brand new virus—that’s the thing about it…While you can guess a bit from the past, you really have to learn from the present.”

Dexterity, agility and flexibility are all key in infectious diseases research, Lane said.

“The tools we developed to rapidly respond to Ebola outbreaks have been used to rapidly respond to this outbreak. We have staff throughout the institute who are very skilled at adapting assays to new pathogens and establishing clinical trials in austere environments…Also one of the great virtues of the Intramural Research Program and its elements is the ability to turn on a dime and respond in an instant.”

In fact, Lane noted, through an international clinical study that the NIAID Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases is conducting, NIH is playing an important role in the clinical research response to COVID-19.

“We have an active protocol to test the efficacy of the investigational antiviral agent remdesivir,” he said, “and I anticipate as this outbreak unfolds, we will admit patients to the CC to participate in that protocol [see sidebar below].”

Does the risk of getting infected himself ever concern Lane as he rushes into various disease zones?

“It’s what we do,” he said. “That’s part of our mission. We study infectious diseases, so we go to where the infectious diseases are. We know about infection control. I did not have any direct contact with patients. We were in hospitals, but in areas where they were doing fever checks before anyone entered the areas. There’s some risk to anything that one does, but this is what you sign up for when you go into this career path. I worry as much about seeing a patient in the Clinical Center with drug-resistant TB as I do about going to China to look at COVID-19.”

Health care worker infections in China occurred early in the outbreak, he continued, “before they had a sense of what was evolving. Health care worker infections are now rare in China, and these are the people directly taking care of the patients. The same has been the case with Ebola. When you take the proper precautions and pay attention to detail, you can substantially minimize the risk to the health care worker.”

Still, he said, coronavirus is not to be taken lightly. “China adopted extreme social- distancing policies and the Chinese scientific community has been contributing substantially as well—including rapidly identifying and sequencing the virus and making the sequences publicly available.

“If there were more opportunities for collaboration between the Chinese research community as a whole and the U.S. research community as a whole, that could be of benefit,” Lane concluded. “The cities, hospitals and laboratories in China are state-of-the-art. There’s so much going on there that I think they could be a valued scientific partner, if one can get over the political hurdles.”

China demonstrated that rapid implementation of extreme social distancing led to fairly rapid control of the outbreak, Lane observed. “That’s a good lesson. There are probably lessons that everyone could take for influenza as well. People coming in to work when they’re even a little bit sick is not in the best interest of public health and puts the health of other individuals at risk.

“The lesson going forward is that there are ways you can prevent the spread of a respiratory disease,” he said, “but everyone has to take personal responsibility. It’s not an issue of the individual being tough enough to work through the illness. That’s not the issue. The issue is, you go to work and you infect your coworkers. It’s a matter of whether you care enough about your coworkers to minimize their risk of infection.”