Coronavirus Avalanche

Covid-19 Lessons from the Austrian Alps

Two or 3 years ago—at least it feels like that—the town of Ischgl in the Austrian Alps was hosting a lively après-ski nightlife. It was early March 2020, and busloads of vacationers from nearby slopes were flocking to the town’s bars, boosting a normal population of 1,867 residents into something north of 10,000. Before the month was out, more than 10,000 people would be infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Ischgl, or by someone who had visited there.

But astonishingly, only two people in Ischgl would die of Covid-19, the disease caused by the virus, even though a subsequent study by researchers at Innsbruck Medical University would show that more than 42 percent of those living in Ischgl carried coronavirus antibodies, among the highest rates of seroprevalence ever detected [Bergamo, in Italy, had rates of more than 60 percent].

As virologist Dr. Dorothee von Laer of the university walked an NIH Covid-19 scientific interest group lecture audience through a virtual reenactment of these events on July 1, the virus was raging uncontrolled: more than 10 million cases worldwide, another 8 million to 10 million cases not yet diagnosed, half a million confirmed deaths and more than 160,000 daily new infections, as of that date.

“It’s remarkable how this little particle of around 10 nanometers can have such a devastating effect,” she said, noting that it is estimated that 1 infected cell can produce thousands of new virions in only 12 hours.

Europe’s pandemic began in France and Italy, then spread to Germany and the rest of Europe, said von Laer. “Ischgl was a gateway. It set off a coronavirus avalanche.”

Early in March, tourists returning from Ischgl (pronounced “ISH-guel”) to Iceland started coming down with Covid-19. On Mar. 5, authorities in Tyrol state posted a notice of risk. Five days later, all of the town’s bars were closed.

“There was a big exodus—everyone left town in 3 days, Mar. 11–13,” said von Laer. On Mar. 14, the ski resort shut down. “From Mar. 13 through the end of April, the whole valley was quarantined. Forty percent of all Covid-19 cases in Austria were traced to Ischgl.”

Cellphone tracking data confirmed that Ischgl was an epicenter of Covid-19, she said.

“We are not very experienced with big clinical trials at my medical center,” von Laer admitted, “but we do have a big diagnostic institute.”

She and her colleagues set out to determine the seroprevalence of the virus, the incidence of cases, the number of children infected and to trace the history of the outbreak, using mathematical models.

They enrolled 1,536 people, or 82 percent of all residents in Ischgl, testing blood for viral antibodies with 4 different assays, using PCR tests on samples from throat swabs and collecting questionnaires. Testing positive were 624 people, or 42 percent of the study population. Blood samples from the community taken in 2019, pre-pandemic, served as controls.

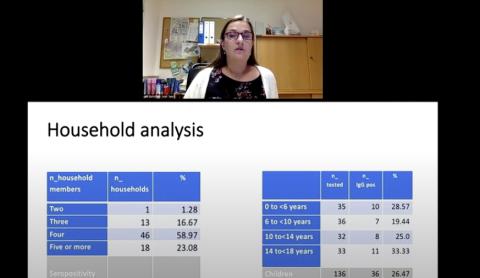

The researchers also did a household analysis that included 136 children and 184 adults from 78 homes, 22 of which experienced no infections.

“It was absolutely not the case that the virus would sweep through the household,” von Laer reported. “We find this very interesting…This group of people that were highly exposed but not infected is a population of interest to us.”

In couples where only one person was infected, Covid-19 was transmitted to the other only about half the time.

“That shows us that the virus is not as contagious as one would have thought,” she said.

Out of all seropositive adults in the study, only a few needed hospitalization, von Laer continued; 83 percent did not know that they had a previous coronavirus infection. Children, in general, became less ill

than adults.

“The crucial event in the control of super-spreading was closure of the bars,” she concluded. “There was a strong decline in Rt [a measure of how fast a virus is growing in a population] after the bars closed.”

As routine interventions such as social distancing and mask-wearing helped control virus spread, mathematical models conclude that the high seroprevalence significantly contributed to the drastic decline of new infections during April, said von Laer. Yet herd immunity has not yet been reached, “despite very good virus control.”

During a Q&A session, she noted that Ischgl’s high infection rate is much higher than in the nearby ski resorts, which tend to have a quieter nightlife.

“[Ischgl] is a party hot-spot,” she said. “People come in buses, hundreds every evening. It’s a very good place for a virus…The music is very loud, people are shouting, they are in a closed space and they’re there all night.”

Von Laer was also asked if it is worthwhile to achieve herd immunity without a vaccine, as has been proposed in Sweden.

“That is an ethical and political question, not a question for virologists,” she said. “But to achieve herd immunity, there would be at least 25,000 deaths in a country as small as Austria. As a doctor, I think that preventive measures are necessary and important. But if improving the economy is worth it to you, you can let 25,000 people die so we can go out and buy all sorts of stuff we don’t need.”

The full lecture is available at https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=38084.