‘Little by Little’ Supports Habit Formation, Says Kim

Photo: Habit Design

Most of us have heard the “pernicious and insidious” myth that it takes just 21 days to form a new habit or change a behavior, said Michael Kim, founder & CEO of Habit Design, the first habit coaching company to be awarded an NIH Small Business Innovation Research Fast Track grant.

“Based on the latest clinically validated scientific research, we now know it actually takes much, much longer than that to form healthy habits that matter—it’s more like 66 days or longer,” said Kim during a Sept. 15 webinar presented by the NIH Strategic Change Community of Practice.

Grit and determination alone will not help people reach this threshold, he explained. Inevitably, they become stressed, burn out and, eventually, stop trying. He noted that people must realize “the only way to act upon our intentions without expending precious willpower is through habits.”

Every behavior lives within a sequence of preceding and subsequent behaviors, he explained. If, for instance, a person wants to learn how to high jump, he or she would work with a coach to learn the actions that come before and after the take-off.

“You’re learning how to apply various key steps into your daily routine to execute towards the new habit,” Kim said. “This is what’s called shaping, a conditioning method that applies positive reinforcement to progressive steps towards a goal.”

To accelerate habit formation, he advised identifying three behaviors that must follow one another. This chain of behaviors is what Kim calls a habit design. Each part of the sequence must happen immediately after the other.

First, people should think about what he calls the “minimum viable incremental dosage” of a habit. For example, if a person wants to start a new walking routine, he or she should begin by walking one block. Then, slowly increase the distance by another block. Even though it sounds simple, it’s not easy.

“Many people start by doing way too much, which might feel good when they are rested, ready and motivated,” he said. “We tell people, ‘Little by little, a little becomes a lot.’”

Next, a person must identify an existing habit that he or she already performs without much conscious effort in the same physical location every day. This is called an anchor step. A person might, for example, put shoes on every day to go outside to retrieve the mail. From there, it’s easier to walk one block because that person is already out of the house.

The final part of the sequence is to insert a step between the first and last one that makes it easier to do the habit. This is called a trigger step. It locks a person into following through. For instance, after a person retrieves the mail from the mailbox, he or she might leash the dog.

“My dog makes it virtually impossible for me not to walk with him once I put on the leash,” Kim said.

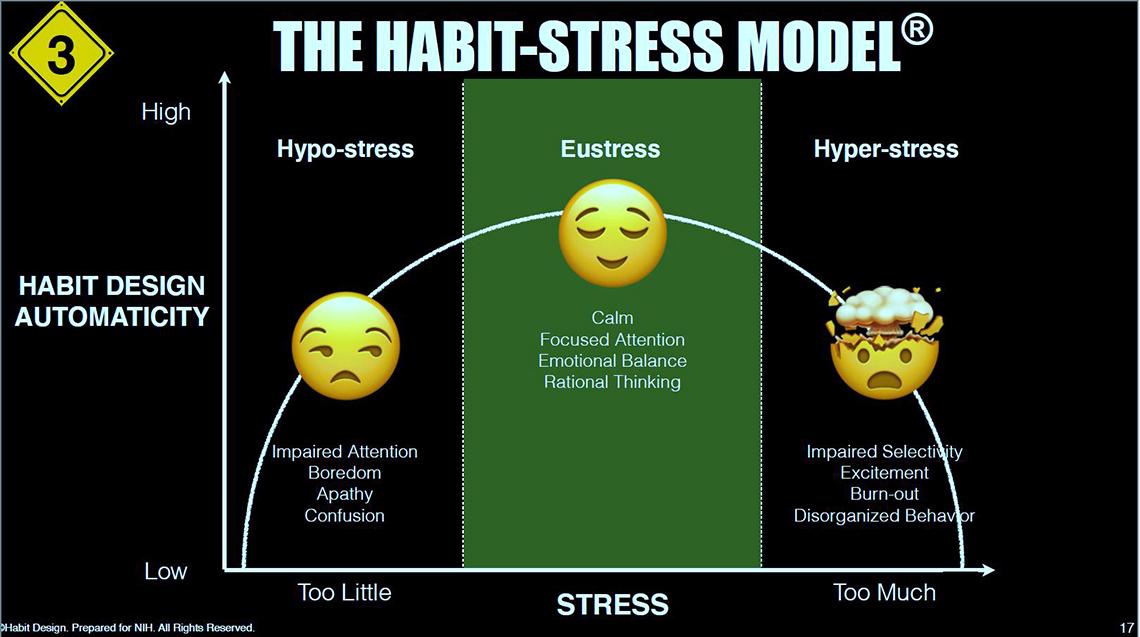

Our brains are wired to respond negatively to new challenges, even if those challenges are beneficial, he explained. When a person is pushed beyond what he or she can handle, habit formation will “suffer from the impact of what clinicians call ‘hyper-stress.’” In this state, little things can trigger a strong emotional response. On the other hand, it’s also possible to have too little stress to be effective in forming a habit successfully.

Photo: Habit Design

There is a happy medium called “eustress,” which is “positive stress that arises from increased physical activity, enthusiasm and creativity.” Eustress arises when motivation and inspiration are needed. A concert musician might, for example, experience butterflies before a show. This is where habits thrive. As habits become more automatic, the greater the likelihood of creating eustress.

“What the latest clinical research tells us is that it’s not reducing hyper-stress that makes performing habits possible,” Kim said. Rather, it’s the reverse: making habits more automatic reduces hyper-stress.

Changing behavior and creating lasting habits often fail in large organizations because employees are frequently resistant to being changed by an organization, even if they themselves agree with the proposed changes. Kim said employees engage better if they first learn together how to change behaviors of their own choosing for their own benefit before addressing any evangelized behaviors from their organization.

From analyzing the long-term effects of training more than 100,000 employees, Kim and his clinical team observed that, after a year, trainees found an additional 5 minutes of productivity per hour, per day on average. Those extra minutes of productivity can add up to an extra day of productivity per week or, from another point of view, 8 weeks of vacation per year, saving one prominent Silicon Valley law firm almost $3 million each year. McKinsey & Co., a partner, published independently conducted research showing a 180 percent return on investment from applying habit training to address obesity in the U.K.

“Five minutes an hour might not sound like a lot, but within the context of a year and for an organization where time is literally money, 5 minutes is tremendous,” Kim concluded. “But little by little, a little becomes a lot.”