Mending Broken Hearts

Fellow Explores DeBakey’s Far-Reaching Legacy

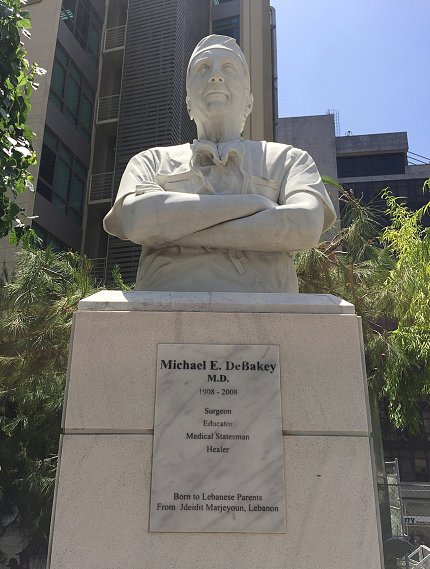

The late Dr. Michael E. DeBakey is a medical legend. Dubbed the Texas Tornado by a colleague, DeBakey—a cardiac surgeon, innovator, educator and research advocate—inspired countless doctors and medical students in the United States during his 75-year career. His scientific contributions and teachings also transcended national borders. The son of Lebanese immigrants, he was especially revered across the Middle East.

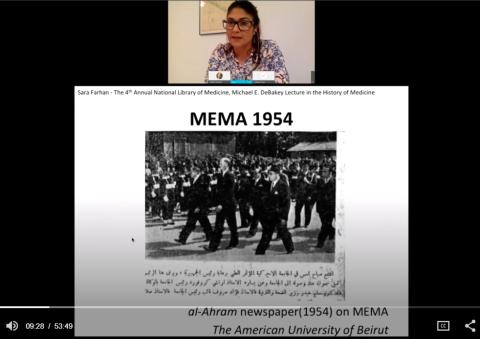

The National Library of Medicine houses an archive of DeBakey’s seminal papers and further honors his legacy by hosting a namesake annual fellowship program and lecture. Recently, Dr. Sara Farhan, one of six 2019 DeBakey fellows, spoke via videocast to offer the 4th NLM Michael DeBakey Lecture in the History of Medicine.

“DeBakey’s heritage was a source of pride not only to doctors, but also to the general population in the Middle East,” said Farhan, an Iraqi-born scholar. “When mentioned, almost always, his Lebanese heritage is underscored alongside his innovation, research and professional accomplishments.”

Photo: Baylor College of Medicine

The pioneer of open-heart surgery, DeBakey designed cardiac pumps and surgical instruments, some of which are still used today. Having learned to sew from his mother, in the early 1950s, he stitched the first Dacron grafts to replace sections of blood vessels damaged by aneurysms.

In the 1960s, DeBakey performed the first successful coronary bypass and some of the first heart transplants. He performed more than 60,000 surgeries in his lifetime and operated on some internationally prominent figures, including the shah of Iran and members of the Saudi royal family. During his 50-year affiliation with Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, where he was chief of surgery, he trained surgeons from around the world.

Farhan, who teaches history at the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates, has been researching the internationalization of the medical profession—with a focus on medical schools in Iraq and Lebanon—and DeBakey’s historic role in the process. She highlighted his April 1954 visit to the region during which he attended the Middle East Medical Assembly (MEMA) at the American University of Beirut (AUB).

DeBakey’s attendance at MEMA was significant on multiple levels and was viewed as an opportunity to bolster international ties among surgeons and medical professors.

“Doctors in the Middle East were members of an international professional community where the exchange of knowledge was rooted in lifelong learning,” Farhan said. Their networking with other prominent doctors from around the world symbolized that they did not work in a vacuum, she added, helping to dispel notions of the Middle East as a backward, isolated region.

From Beirut to Baghdad, doctors embraced new developments in medicine and had been captivated by DeBakey’s life-saving cardiovascular innovations for years.

“DeBakey’s footprints in the Middle East were planted prior to his 1954 visit,” Farhan said. “Medical colleges in the Middle East studied, applied and taught DeBakey’s findings. His name was part of the medical lexicon in the region.”

The 1954 MEMA came at an auspicious time, when medical educational ties were flourishing between the United States and the Middle East. After World War II, anti-colonial movements across the Middle East presented new opportunities for collaboration. As ties weakened with France and England, the two major colonial powers, students and doctors increasingly sought training at American colleges, said Farhan.

Photo: Embassy of Lebanon

During this period of heightened Arab nationalism, the work of medical pioneers of Arab descent, including DeBakey—whose Lebanese family name was Dabaghi—gained growing attention across the region. “DeBakey became an extension of the region’s contribution to the history of advancement in modern medicine,” said Farhan.

Against this backdrop, it’s not surprising that the U.S. State Department encouraged DeBakey to travel to Beirut for the MEMA in 1954.

“I speculate that the State Department hoped DeBakey would establish new ties in Beirut in hopes of persuading doctors and politicians alike to consider the United States as a worthwhile ally for medical meetings, missions and campaigns,” said Farhan.

The MEMA conference lasted 3 days, but DeBakey would remain in the Middle East for a month, lecturing and touring at 5 medical colleges in 3 countries. His lectures mainly focused on the science. But in Syria, where he traveled to two medical colleges with a local doctor, DeBakey boldly expressed concern that Arab nationalism—instruction in Arabic and the ban on foreign language books—was hindering international networking opportunities there.

Medical journals in the Middle East had cited DeBakey’s work as early as 1940, describing his sleeve-valve transfusion syringe, one of his first inventions back in medical school at Tulane University.

“But the exchange of knowledge was not one-directional,” said Farhan. DeBakey collaborated with surgeons and had studied the works of doctors from the region, including prominent Iraqi surgeon Dr. Yousif al-Naaman and AUB’s Dr. Amin Khairallah.

“This is especially important because it highlights that DeBakey celebrated the knowledge exchange shared between the Middle East and the United States,” Farhan said. “He did not see himself as superior to medical professionals in the region, but as their equal.” His relationships with medical professionals across the Middle East continued to flourish for decades, until his death in 2008.

Farhan closed by sharing a poem she came across in NLM’s archival collection that she thought highlighted DeBakey’s influence on the region. In his 1953 A Brief Medical Bible: Ethics in Medicine, Khairallah wrote: “Today well-lived makes every yesterday a dream of happiness, and every tomorrow a vision of hope.”