Housing Segregation a Central Cause of Racial Health Inequities

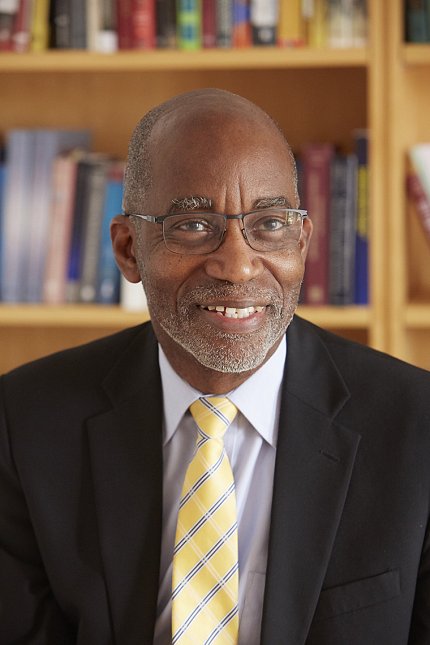

Structural racism in the housing system is a fundamental cause of racial health inequity in the United States, said Dr. David Williams during a recent NIMHD/NINR Joint Directors’ Seminar on the Science of Structural Racism.

“We will not make the progress we would like to make in reducing health inequities if we don’t address it,” said Williams, professor of African and African-American studies at Harvard University and the Florence and Laura Norman professor of public health and chair of the department of social and behavioral sciences at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Structural racism—also known as institutional or systemic racism—is a societal system that “categorizes and ranks populations and groups, devalues and disempowers some groups,” he explained. It “leads to the development of negative attitudes and beliefs, prejudice and stereotypes, differential treatment and discrimination by both individuals and societal institutions.”

Residential segregation, or “the physical separation of the races by forcing residents into different areas,” is one of the most prominent examples of structural racism. The system was developed in the South and expanded to the North. He said it has been “locked in place” since 1940.

Historically, the segregation of African Americans has been unique. While other groups are segregated depending on income levels, segregation is higher for African Americans at all income levels. But not by choice.

“Studies show African Americans show the highest preference for residing in integrated areas [compared to] any other group,” he said.

Williams compared segregation to toxic emissions produced by an industrial plant in a neighborhood. Both are often imperceptible and cause illness and death. When they appear, valuable resources such as quality schools, safe playgrounds and housing, good jobs, clean air and water, transportation and health care, all disappear.

In the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the U.S., studies show two-thirds of all African-American children, 58 percent of Latino children and 53 percent of indigenous American children live in low-opportunity neighborhoods. Almost two-thirds of non-Hispanic whites and Asian kids live in high- or very high-opportunity neighborhoods.

“There are striking differences in access to opportunity at the neighborhood level,” Williams said.

Residential segregation is just one aspect of systemic racism. Other examples include immigration and border policy, political participation, the criminal justice system, workplace policies and home mortgage discrimination.

Acts of interpersonal racism also adversely affect health, he noted. Everyday discrimination, such as being treated with less courtesy and respect or receiving poorer service, predicts adverse health outcomes that have enormous health consequences, such as higher levels of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, breast cancer, poorer sleep and obesity.

People who experience these little indignities are biologically older than their chronological age, Williams said. Some research studies found African Americans are biologically 7.5-10 years older than non-Hispanic whites who are the same chronological age based on their physiology.

“One of the consequences of this is the earlier onset of diseases and greater severity of diseases,” he said.

Going forward, Williams said public health researchers must better understand how poor neighborhoods and substandard housing lead to stress. They also need to identify exposure to non-traditional stressors, such as the viewing of traumatic videos of persons being beaten, arrested or detained or being shot by police, that adversely affect health.

“Addressing segregation will not be easy,” Williams said. “There are deep fears of segregation and its impact on the United States.”

Williams indicated that although there are not many success stories, there is the Purpose Built Communities model that shows it is possible to create mixed-income housing that addresses all of the challenges faced by poor communities simultaneously, and markedly improve public safety, education, employment and child care.