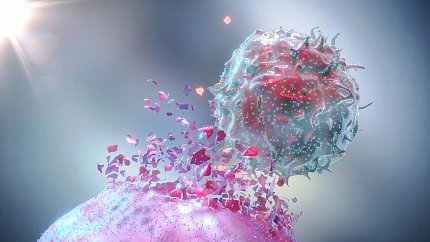

Engineered Immune Cells Prevent Cancer Spread

Scientists have genetically engineered immune cells, called myeloid cells, to precisely deliver an anticancer signal to organs where cancer may spread. In a study of mice, treatment with the engineered cells shrank tumors and prevented the cancer from spreading to other parts of the body. The study, led by NCI scientists, was recently published in Cell.

“This is a novel approach to immunotherapy that appears to have promise as a potential treatment for metastatic cancer,” said the study’s leader, Dr. Rosandra Kaplan of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research.

Before cancer spreads, it sends out signals that get distant sites ready for its arrival. These “primed and ready” sites, discovered by Kaplan in 2005, are called premetastatic niches.

In the new study, the NCI team looked at the lungs of mice after tumors formed in the leg muscle but before cancer reached the lungs.

Normally, when myeloid cells detect a threat, they make interleukin 12 (IL-12), a signal that alerts and activates other immune cells. But myeloid cells in the lung premetastatic niche instead sent out signals that told cancer-fighting immune cells to stand down, the researchers found.

The NCI team wondered if they could manipulate the myeloid cells to deliver a different message that would spur the immune system into action. So, they used genetic engineering to add an extra gene for IL-12 to myeloid cells—nicknamed GEMys—from lab mice.

The GEMys produced IL-12 in the primary tumor and in metastatic sites. As hoped, GEMys recruited and activated cancer-killing immune cells in the premetastatic niche and lowered the signals that suppress the immune system.

“We were excited to see that the GEMys ‘changed the conversation’ in the premetastatic niche. They were now telling other immune cells to get ready to fight the cancer,” Kaplan said.

As a result, mice treated with GEMys had less metastatic cancer in the lungs, smaller tumors in the muscle, and they lived substantially longer than mice treated with nonengineered myeloid cells. The researchers found similar results in mice with pancreatic tumors that spread to the liver.

The NCI team also found encouraging results when combining GEMy treatment with chemotherapy, surgery or T-cell transfer therapy. When the researchers reintroduced cancer cells into mice that had been cured by the combination treatment, tumors didn’t form. This suggests the combination treatment leaves a long-lasting “immune memory” of the cancer.

As a final step, the researchers created GEMys from human cells grown in the lab, which produced IL-12 and activated cancer-killing immune cells. Next, the team plans to test the safety of human GEMys in a clinical trial of adults with cancer.