Two Families Grapple with Rare Disease Diagnosis, Finding Treatments

Photo: Niclas Flysjo

It’s agonizing for parents to watch their children suffer and not know how to help them. When parents learn their child has a rare disease, consumed with grief and fear, they try to navigate the confusing medical lingo for diseases that have limited resources and few, if any, effective treatments.

Two families were among those who shared their rare disease journeys during NIH’s Rare Disease Day virtual event on Mar. 1. In both cases, their babies were born seemingly healthy. Then, around age 2, worrisome symptoms appeared that led these families to seek a medical evaluation.

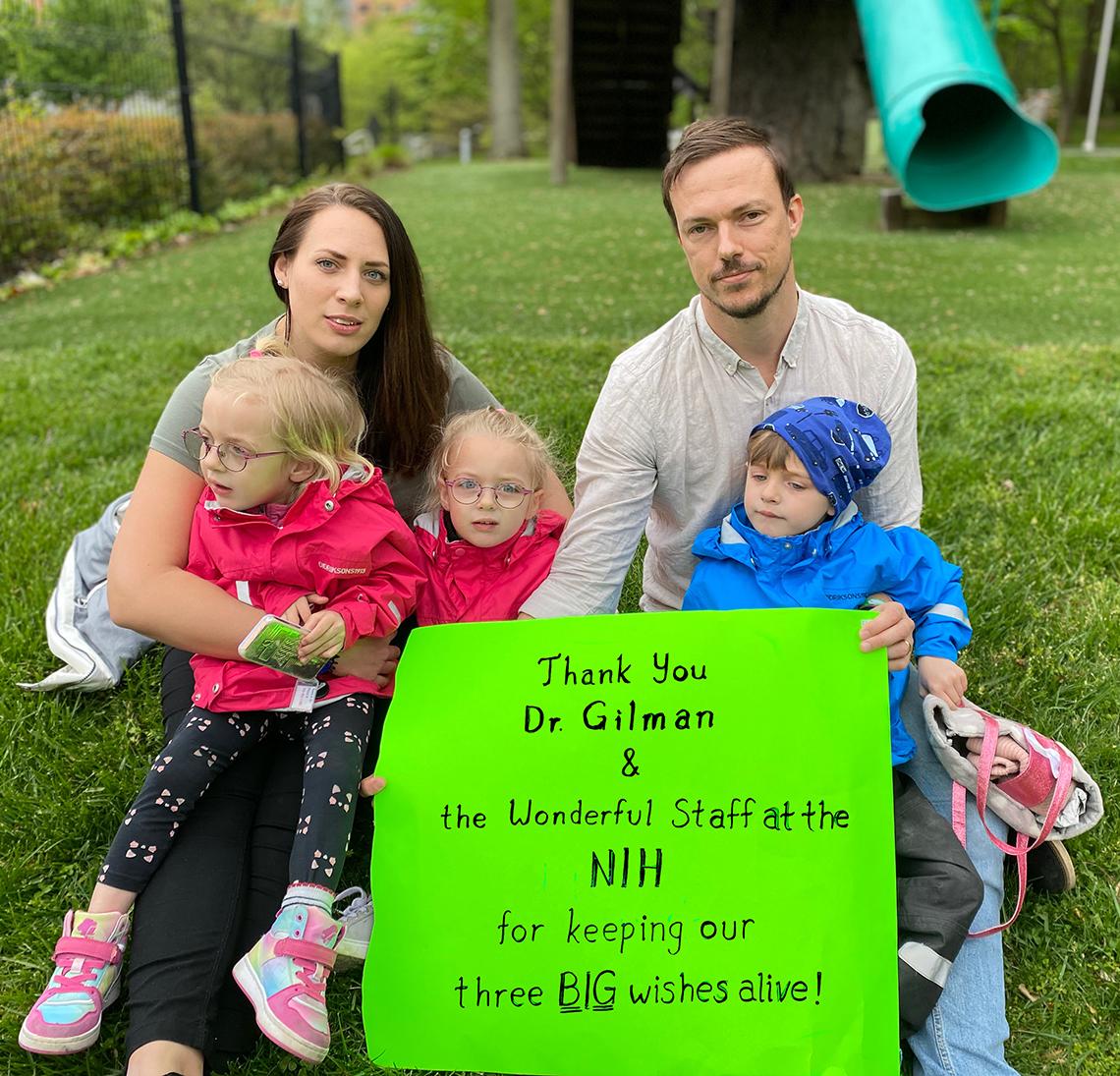

In March 2020, a family arrived at NIH, having flown from Sweden just days before the Covid-19 pandemic closed the U.S. border to flights from Europe. The couple’s three young children were set to begin a groundbreaking clinical trial.

Photo: Niclas Flysjo

Niclas and Jessica Flysjo recounted how their 5-year-old son Hampus began having trouble with balance and speech at age 2. After 18 months of tests, a neurologist informed them Hampus had a rare, fatal genetic disorder called GM1 gangliosidosis. Soon after, they took their then-2-year-old twin daughters, Isabella and Julia, to get tested and learned they also had this recessive, neurodegenerative disease.

Devastated, the couple connected with foundations and heard about gene therapy research. “For the first time since the diagnosis, we found a spark of hope, and we began to research everything there is to know about first-in-human gene therapy,” said Jessica.

Months later, they learned of a small, first-in-human gene therapy trial at NIH, headed by Dr. Cynthia Tifft, NHGRI deputy clinical director. It would be an open-label study, meaning there were no placebos; every child would get the experimental treatment. The 3 Flysjo youngsters would be among 8 children accepted into the study.

“It took months to complete all the necessary tests and waiting for each result was nerve-racking,” Jessica said. “Our journey could end at any point for any of our children.”

The thought of receiving an immunosuppressing treatment in the middle of a pandemic was frightening, said Niclas, but postponing treatment could mean Hampus’s disease progression might disqualify him from the trial.

The gene therapy was administered in April 2020. Within weeks, the children headed to recuperate at the Children’s Inn, where they stayed for the next 6 months. It’s still too early to know whether the treatment is working, but the Flysjos are grateful for the opportunity of a treatment that may save their children’s lives.

Throughout the RDD event, patients or families of patients, advocates and clinicians offered their perspectives. One presenter, Dr. Tracy Dixon-Salazar, is all three: a concerned parent whose daughter has a rare disease, patient advocate and researcher. Wondering if she needed a Ph.D. to understand her daughter Savannah’s rare disease led her to pursue a neuroscience doctorate.

Savannah’s daily seizures began at age 2. Three years later, she was diagnosed with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS). From ages 2 to 18, Savannah would have more than 40,000 seizures and tried and failed 26 different treatments.

“With every doctor we saw across our journey, we would hear different things about LGS, so there’s not even an institutional knowledge about it,” said Dixon-Salazar, who is executive director of the LGS Foundation.

One doctor told her it didn’t matter whether LGS was the correct diagnosis because, if need be, they could try all the dozens of seizure medications out there.

Photo: Tracy Dixon-Salazar

“It strikes me as [counterintuitive]–the mammoth costs associated with this, the confusion for the patient,” said Dixon-Salazar.

“A number of times, I learned something from the medical record or from a scientific talk I otherwise wouldn’t have been at,” she said, advocating for improved health literacy for all rare diseases. “We use a lot of these big words that don’t really mean anything to patients. Trying to get to the bottom of what [the terms] mean can be really challenging.”

Dixon-Salazar recommends more plain language—and common institutional language—for rare diseases as well as more community engagement, funding and global coordination.

For anyone living with a rare disease, better health literacy can help promote access to appropriate medical care, improve patient quality of life and lay the groundwork for successful clinical trials and better treatments.

Photo: Niclas Flysjo