NIDDK Diabetes Research Cited

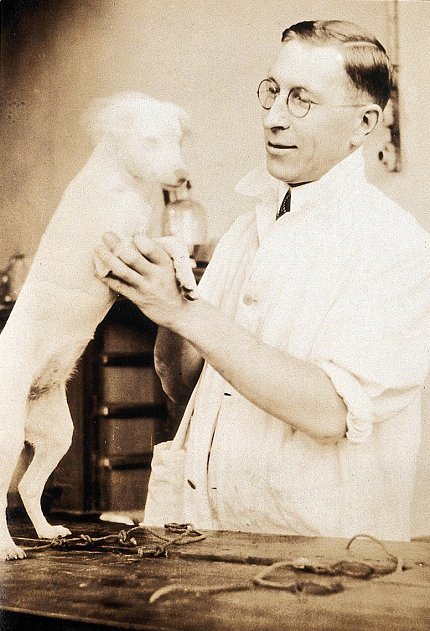

Century of Insulin Celebrated

In the summer of 1921 at the University of Toronto, after months of failed experiments, Drs. Frederick Banting and Charles Best made a profound discovery. They found that a pancreatic extract from healthy dogs reduced blood glucose in other animals with diabetes. By the following year, that extract was chemically refined and used in human clinical trials to treat people with type 1 diabetes. Called insulin, the extract would change type 1 diabetes from a fatal condition to one that could be managed.

In the 100 years since, tremendous progress has been made in diabetes research and care. By 1936, the glucose tolerance test was developed and two types of diabetes emerged: insulin-sensitive and insulin-insensitive–now known as type 1 and type 2 diabetes, respectively.

From its very beginning in 1950, NIDDK conducted and supported laboratory, clinical and population research to understand diabetes, metabolic, endocrine and related diseases.

“NIDDK has leveraged the discovery of insulin to play a critical role over the last 70 years in advancing diabetes research,” said NIDDK director Dr. Griffin Rodgers, in a video reflecting on insulin’s 100th anniversary.

The reflections were part of a recent virtual symposium commemorating insulin’s discovery.

During symposium opening remarks, NIH director Dr. Francis Collins said, “I look forward to witnessing the next steps that researchers presenting and attending this meeting are going to take along the path first cleared by Banting, Best and their collaborators a century ago. Let’s make the next century of diabetes one where we figure out how to prevent and cure this disease so that it goes into the history books.”

New Approach to Type 1 Diabetes

Photo: Wellcome Collection

NIDDK-supported research made an important impact on advancing understanding about type 1 diabetes. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) started in 1983 to see if people with type 1 diabetes who kept their blood glucose levels as close to normal as could safely be achieved could delay development of diabetes-related complications such as eye, kidney and nerve disease, compared with people who used the conventional treatment at the time of the study.

The trial became a landmark success. DCCT ended after 10 years in 1993—a year earlier than planned—when the study showed that participants could significantly lower their chances of developing diabetes-related complications by keeping their blood glucose levels close to normal. Its long-term follow-up study, called the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC), has followed DCCT participants since the trial ended and showed that continuing the tight management of blood glucose levels helps people with type 1 diabetes live a normal-length life.

“The DCCT/EDIC findings were paradigm changing and were quickly adopted worldwide and incorporated into the standards of care for people living with diabetes,” said Dr. William Cefalu, director of NIDDK’s Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolic Diseases (DEM). “This NIDDK-supported research favorably changed the way we view the management of diabetes forever.”

Photo: NIH Office of History

Much of NIDDK’s type 1 diabetes research funding comes from the Special Statutory Funding Program for Type 1 Diabetes Research, or Special Diabetes Program (SDP). This appropriation approved by Congress has provided more than $3 billion over 24 years to support innovative trials and research networks for the prevention, treatment and cure of type 1 diabetes.

SDP has supported the development of cutting-edge technologies that have made daily management of diabetes easier, such as the continuous glucose monitor (CGM). In the last few years, artificial pancreas technology has eased the management burden. The devices automatically monitor and regulate blood glucose using a CGM and insulin pump programmed with dosing algorithms tailored to the user. Through decades of NIDDK-supported clinical testing and trials, multiple artificial pancreas devices have been approved by the FDA.

Breaking Through on Type 2 Diabetes

Photo: niddk

NIDDK’s role in type 2 diabetes research had an earlier start. By the 1960s, the institute began the first long-term population study among American Indians to understand causes and risk factors for type 2 diabetes and its complications. One of the first collaborations of its kind, the study was conducted in partnership with the Gila River Indian Community, the Indian Health Service and other academic partners.

NIDDK’s Dr. William Knowler, chief of the NIDDK diabetes epidemiology and clinical research section in Phoenix, was a principal investigator with the study, which uncovered the alarmingly disproportionate burden of diabetes and its complications among American Indians.

“One of our important early observations was that type 2 diabetes occurs in American Indian children,” Knowler said. “It was previously assumed that almost all diabetes in children was type 1 diabetes, which has a different pathogenesis from type 2 diabetes that was previously thought to occur only in adults. Type 2 diabetes is now recognized as a major form of diabetes in U.S. children, especially those from certain racial and minority groups.”

The study also revealed risk factors for type 2 diabetes, some of which—obesity, for instance—had the potential to be modified to reduce risk or delay onset in those at high risk.

Photo: DPPOS Research Group

The NIDDK-funded Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) was launched in the 1990s to examine whether an intensive lifestyle intervention for weight loss or the medicine metformin would delay or prevent type 2 diabetes among people at high risk for the disease.

Three years into the 4-year study, the trial stopped early because of the significant benefits seen among participants in both of the study’s treatment groups.

The study found that people who are at high risk for type 2 diabetes can prevent or delay the disease by losing a modest amount of weight, about seven percent of their starting weight, through lifestyle changes—regular physical activity and a diet low in fat and calories.

Participants in the lifestyle program reduced their incidence of diabetes by 58 percent during the 3-year study. The generic drug metformin also prevented the disease by about 31 percent.

“This was a very exciting time for all of us involved in the study,” said Knowler, who also served as a DPP principal investigator. “The large magnitude of the lifestyle effect was much greater than we had hoped for. And because the intervention effects were uniform among the participants from different racial and ethnic groups, and geographic areas, the results changed the way people approach type 2 diabetes prevention worldwide.”

Blazing a Future of Innovation, Better Health

As NIDDK continues to support innovative research, a new area of exploration focuses on the ways in which diabetes varies among people, even among those diagnosed with the same diabetes type. In fact, some forms of diabetes don’t fit any of the known types or causes.

A new NIDDK-funded study called RADIANT (the Rare and Atypical Diabetes Network) seeks people with these unknown or uncommon forms to help understand the broad spectrum of diabetes.

“Through RADIANT and other studies like it, we hope to gain insight into the more common differences present within the broad spectrum of type 2 diabetes and develop diagnostic criteria for new forms of diabetes,” said Dr. Christine Lee, DEM program director and RADIANT project scientist. “Precision medicine will play a key role in the future of personalized diabetes care. Because we know that one size doesn’t fit all, having precise information on prognosis and therapies for a given person will help them form diabetes care plans to meet their individual goals and preferences.”

Many of the last 100 years of advances would not have been possible without the altruism of study participants. Elena Ennis, a study participant with type 1 diabetes who tested artificial pancreas technology, spoke about her experience volunteering in a trial.

“Before I had participated in my first clinical trial, I was very newly diagnosed and everything was so new to me,” she said. “I was worried about what my future would look like. Participating in these trials really has given me a sense of hope as far as the future of living with diabetes. I feel like I have a large support group behind me cheering me on, because researchers are really working so hard to make things better for those of us with diabetes.”

As the century since Banting and Best’s discovery comes to a close, the future of diabetes research—and better prevention, management and, one day, a cure—looks bright.

“NIDDK and the diabetes research community as a whole have made great progress,” Rodgers said. “But our work is not done, and NIDDK will continue working toward finding prevention methods, better treatments and, one day, a cure for all types of diabetes.”

To watch the videotaped reflections, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xI2e76BQZgA. To view the virtual symposium, visit day 1 and day 2.