Friendship Archaeology

Professor Mines NLM Archives for Medical Biography

Dr. Annmarie Adams is an architectural historian who teaches at McGill University in Montreal. Currently, she’s digging through letters, diary entries, photos and other materials to gain insights into the life of the late Dr. Maude Abbott, a renowned researcher at McGill a century earlier.

Adams came to the National Library of Medicine to excavate its collection of related papers and letters. Her timing was auspicious; she visited NLM in October 2019, a few months before the pandemic would hit, restricting travel.

In March, Adams—a professor at McGill’s School of Architecture and chair of the department of social studies of medicine—delivered a virtual NLM History of Medicine lecture on Abbott, one of Canada’s first female physicians. It was a fitting tribute during Women’s History Month.

Photo: Courtesy of the McCord Museum

Abbott had spent much of her 46-year career as curator of McGill’s medical museum. An internationally respected researcher, her Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease classified heart diseases and laid the foundation for modern heart surgery.

Throughout her career, Abbott devoted copious time to correspondence. Dozens of medical museums consulted her about how to organize and preserve their specimens, and hundreds of doctors wrote to her inquiring about their cardiac patients.

In her talk, Adams focused on a chapter from her forthcoming biography that contrasts Abbott’s relationship with two influential American physicians: Dr. Emanuel Libman and Dr. Paul Dudley White.

“This chapter, I think, broadens the way we study women’s professional networks,” said Adams, “a subject in which researchers often focus on friendships among women, rather than professional relationships.”

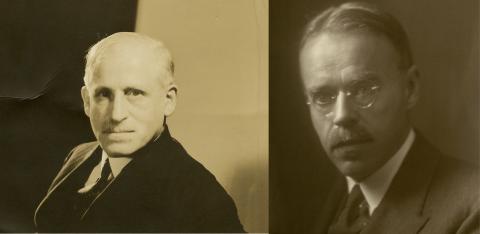

Photo: Libman photo courtesy Chapelle Medical Archives/NYU; White courtesy of Harvard Medical Library

Admittedly, Adams at first assumed Abbott was a mentee of Libman and White when, in fact, she was the senior, more experienced doctor. “These two friendships, as it turned out, were two-directional, perhaps symmetrical, in benefits if not in power.”

Adams calls her research approach “friendship archaeology,” in which she digs deeply into specific places and times to paint a more vivid picture. “Friendship archaeology allows me to frame this work in the evolving history of intimacy,” said Adams, “which offers, I think, a stimulating way to see how these well-known medical figures defined zones of familiarity and comfort.”

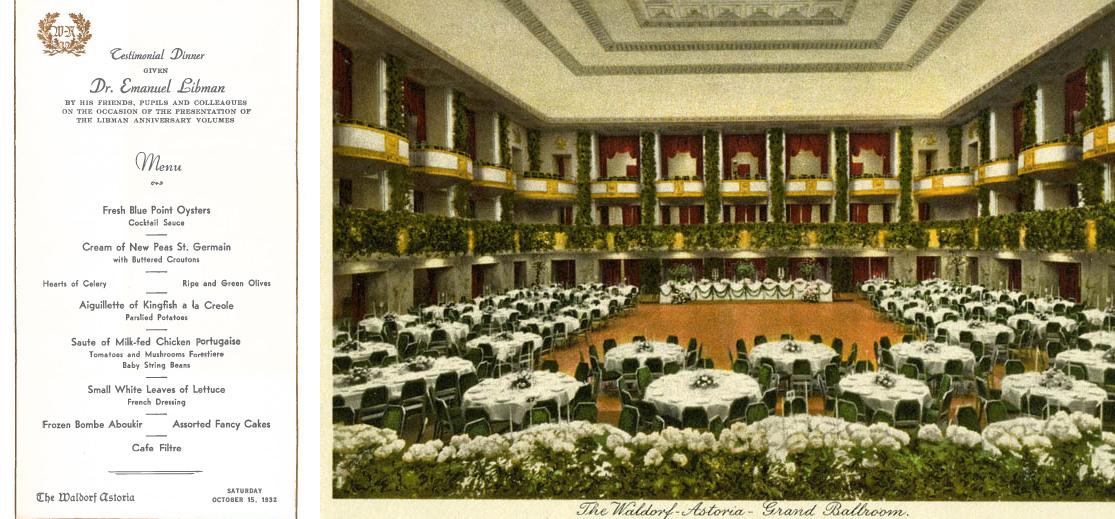

One event that brought her key players together was a 1932 gala dinner at New York’s elite Waldorf-Astoria. At this 60th birthday party for Libman—a prominent cardiologist and philanthropist—600 guests had piled into the ballroom. Abbott, one of few women in attendance, was a featured speaker and, according to published seating arrangements, had a coveted seat among Nobel Prize winners and other notables.

“This role of speaker and [the only woman] sitting at the head table gave Abbott really high visibility,” said Adams. Newspaper coverage of the event described Abbott as “the foremost woman physician in the world.” The gala was but one illustration of “Abbott’s high status as a researcher and physician,” said Adams, that “allowed her to operate as a kind of peer in this Nobel-level stratum, somewhat like an honorary man.”

Photo: Menu courtesy of the Osler Library at McGill University; image at right courtesy of the Waldorf-Astoria

Abbott had a strictly formal relationship with Libman, who consistently—and often anonymously, at his insistence—financed her work.

“I speculate that perhaps Libman’s foreboding character was the reason for their formality,” said Adams. Over the years, Libman and Abbott sometimes dined together, usually at upscale New York restaurants, “which must have been such a treat for Abbott,” said Adams. “It wasn’t the way she lived here.”

And, while she doesn’t mention them in her writings, Abbott was likely fascinated by Libman’s personal collection of organs in jars that he stored in his basement.

“I speculate,” said Adams, “that these ways of being in the world may have endeared him to Maude Abbott, who was also unmarried, childless, lived in the house where she grew up, was somewhat eccentric, had experienced discrimination and, of course, loved things in jars.”

Meanwhile, Abbott’s relationship with White—a distinguished Boston-based cardiologist—was both professional and personal. In work, they reviewed each other’s writings and shared best practices. But Abbott’s diaries reveal a rich friendship with White and his wife Ina, filled with European vacations and many get-togethers.

In June 1935, while Abbott and the Whites were vacationing in Milan and their travel companions were off sightseeing, one of Abbott’s diary entries read, “Wakened early, chocolate shake by the cathedral, then went over the Atlas with Paul.”

Photo: Photo courtesy of Mass General Hospital archives

There don’t seem to be any photos of Abbott together with White or Libman. Their friendships though are well-documented in letters, memoirs, diaries, poetry, house plans, magazine articles, family interviews and at least one mural—prominent Mexican artist Diego Rivera featured Abbott and White in his History of Cardiology mural, painted in 1944, four years after Abbott’s death.

Adams depicts Abbott as a woman who often played a leading role in the spaces and places she shared with her esteemed male colleagues.

“Most biographers of Abbott couldn’t see intimacy beyond sex and marriage,” said Adams. “Her diaries attest, however, to how she was constantly surrounded every day by so-called clinical people who she considered her friends, whom she loved and who loved her.”