Advances in Care Help Save Young HLRCC Patient

When college student Andrew Lee was diagnosed with stage 4 rare kidney cancer in 2015, he would spend the next 4 years fighting it. He knew he might succumb to his illness but hoped his efforts would one day prevent others from suffering. Lee lost his battle in 2019, yet his legacy lives on.

The research Lee enabled—having participated in seven NIH-led clinical trials, donated living tissue and raised nearly $500,000 for rare kidney cancer studies—is already saving lives. One lucky patient is 20-year-old Luke Schmaedeke.

Schmaedeke had known for several years that he could have a syndrome called hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC). Patients with HLRCC are at risk for developing benign renal cysts which, in some patients, lead to the aggressive, lethal form of kidney cancer that took Lee’s life.

In November, at Schmaedeke’s first MRI screening for kidney cancer at the Mayo Clinic, doctors found a small, worrisome mass.

“My anxiety levels started going up,” said Jen Schmaedeke, Luke’s mother, speaking from the family’s home in Minnesota. “We were in shock because here’s this thing [HLRCC] that they’ve said is dangerous. But we’ve been talking about it for years and it hasn’t been dangerous.”

When the call came confirming kidney cancer, “I was still on the phone with the doctor,” said Jen, “but we could hear Luke in the other room, sobbing. It was such a defining moment in his life, and in ours, and it felt like our world was upside down.”

Two days before her son’s scheduled surgery to remove his entire right kidney, Jen was searching online and found the HLRCC Family Alliance. Two hours later, an email arrived from its vice chair, Bruce Hatch Lee, Andrew’s father.

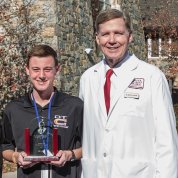

Photo: Bruce H. Lee

“I’ll never forget receiving that phone call on Dec. 27,” said Bruce Lee, president of Driven to Cure, the nonprofit founded by his late son. “We spoke for 90 minutes. I told her, as a patient advocate, if Luke was my son, I’d get a second opinion, especially with the knowledge we now have about not doing radical kidney removals.”

Jen took his advice. Two weeks later, she and Luke arrived at NIH.

“Bruce’s intervention at that critical time was so powerful, not only because he was connecting us with the world’s experts, but also to have someone say, ‘I’m going to walk this walk with you; I’ve been there; I’ve faced the worst; I’m here to help you’ was just amazing. I didn’t realize how much I needed an advocate,” Jen said through tears.

It’s His Choice

Even with their cutting-edge imaging technology, NIH’s radiology team, led by Dr. Ashkan Malayeri, an expert in HLRCC imaging, could not confirm Luke’s mass was malignant. Still, the entire clinical team recommended surgery.

“The amazing thing about NIH’s clinical team is that they work together until they have consensus,” said Lee. “It’s a great, balanced approach and, at the end of the day, the outcome is better.”

NIH doctors told Luke the surgery would entail removing only a portion of his kidney.

Photo: Dana Talesnik

“We have developed a precision surgery approach over the past 32 years and over 500 HLRCC patients,” explained Dr. Marston Linehan, chief of NIH’s Urologic Oncology Branch. “[We don’t] do active surveillance with HLRCC tumors—because they can spread from their smallest one-half centimeter—but recommend surgery when the tumor is detected. We do open surgery and we go wide on our surgical margins, because these tumors can spread and infiltrate throughout the kidney.”

With the chance the tumor wasn’t malignant, Luke decided against surgery. His mother, distraught, called Linehan, who reiterated that it’s Luke’s choice.

“I talked to Luke several times [while he was debating whether to have surgery],” said Lee. “I told him this is a life-and-death scenario and waiting could affect his future outcome. I told him he was in the best place and, even if they couldn’t confirm the cyst was [cancerous], now is the time to get rid of it.”

Still unsure, Luke consulted Linehan again. Linehan told him: Wait until you’re ready but know this won’t get better. You’d be closely monitored and will need surgery at some point.

Luke consented. The next morning, a complex, dangerous-looking mass was removed. The surgeon told him, ‘’We’re very glad it’s out of you.’”

Catching It Early

“For HLRCC, we know the key is to act early, when [cysts] are small,” said Luke’s NIH surgeon, Dr. Mark Ball, who performed a partial nephrectomy, sparing about 85 percent of the kidney.

Luke also benefited from new guidelines—thanks to advocacy efforts led by Bruce and NCI—that recently lowered the recommended age for HLRCC screening from 21 to 8.

“We’ve seen tumors in children as young as 10 and people as old as 77,” said Linehan. Annual screens are critical because HLRCC presents a lifelong risk.

“This is definitely a knowledge is power situation,” said Ball. He tells HLRCC patients, “It can be taxing logistically to screen every year. It’s also anxiety-provoking. But the tradeoff is, if something does come up and we catch it early, it could be a curable event.”

Diagnosing HLRCC

People with HLRCC have a pathogenic variant of one copy of the FH (fumarate hydratase) gene.

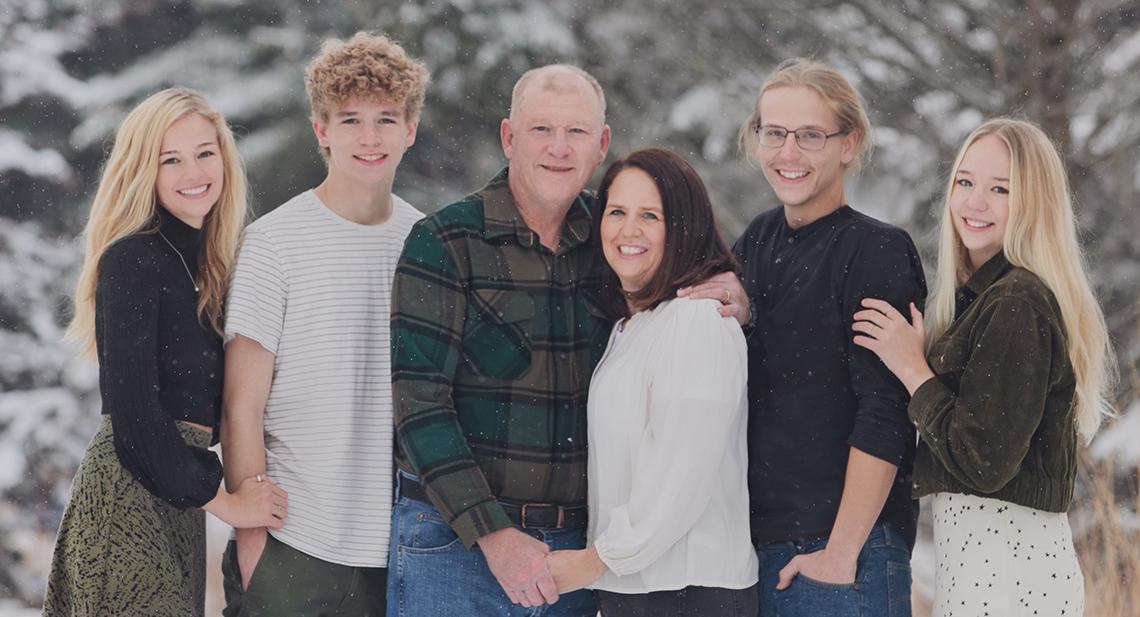

The Schmaedeke family first learned they had this variant in 2013, a year after Jen’s mother, Connie, participated in a research study for breast cancer at the Mayo Clinic. Connie had checked a box on the consent form asking to be notified if any health concerns were identified from her whole-genome screen. A Mayo doctor later called to say she had HLRCC, should get annual scans and alert her family to do the same.

“I was in the middle of raising four teenagers,” said Jen, “and did not pursue testing [at that time].”

Jen learned she had HLRCC in 2016, but waited to test her kids, who were all still under 21. Two years ago, Luke’s older sister, Corrine, got tested when she turned 21 and learned she too had HLRCC.

Although only 19 at the time, Luke spontaneously got tested while tagging along with Corrine for her first annual MRI. Luke tested positive. Getting that first MRI 6 months later likely saved his life.

HLRCC is diagnosed through genetic testing, generally done when there’s a family history of kidney cancer. Another way to diagnose it is by recognizing the signature benign nodules called leiomyomas—the L in HLRCC.

An estimated 15 percent of HLRCC patients develop kidney tumors. “By the time Andrew was diagnosed,” recalled Bruce, “he was riddled with cysts and lesions. HLRCC is too often misdiagnosed or missed altogether.”

Recent Advances

Photo: Dana Talesnik

Tireless advocacy by the Lee family has increased awareness of the disease and the importance of screening. Now, more dermatologists and gynecologists are recognizing leiomyomas, leading to earlier diagnoses and monitoring.

Major advances continue in imaging technology and surgical techniques and for treating patients with advanced disease.

“This approach, developed with and confirmed in clinical trials by NCI oncologist Dr. Ramaprasad Srinivasan, is becoming the worldwide standard for frontline therapy for patients with advanced HLRCC kidney cancer that was based on work in NCI laboratories,” said Linehan. And, by studying donated patient tissue, the team recently made additional discoveries they hope will lead to even better therapies.

The Schmaedeke family discovered firsthand that knowledge is power.

“I realize we could’ve waited until Luke was 21 [to screen and find the tumor],” Jen said. Instead, they caught and removed a tiny tumor when Luke was 19 and he recovered quickly. He was back in class 10 days after surgery and returned to pitching for his college baseball team for the spring season.

Jen is also grateful her mother checked that box on her study form that led to her HLRCC diagnosis.

“All these pieces of the puzzle had fit together to lead us to Luke’s very early diagnosis,” she said. “This is a gift. Luke [initially] didn’t see it that way, but, [looking back], we certainly saw this as a chain of events that ended in something miraculous.”