Intranasal Covid-19 Vaccine Effective in Animal Studies

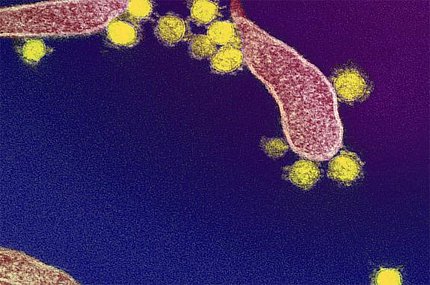

Photo: NIAID

A nasal spray of the Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine protected hamsters and monkeys against serious disease and reduced the amount of virus in the nose. Less virus in the nasal passages could reduce the risk that vaccinated individuals spread the virus. The findings appeared in Science Translational Medicine.

All Covid-19 vaccines now in use are injected into the muscle. This produces antibodies that circulate in the blood to recognize the virus. But intramuscular injection might not produce antibodies in the nose and nasal passage, which has raised the possibility that vaccinated people could still catch and spread the virus, even when they don’t know they’re infected. Vaccines given through the nose may be able to block SARS-CoV-2 in the nasal passages and bloodstream.

In the study, both intranasal and intramuscular administration of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine produced high levels of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, in the blood of hamsters after a single dose.

When vaccinated and unvaccinated hamsters were then exposed to SARS-CoV-2, both vaccine administration routes protected hamsters from serious disease. Unvaccinated hamsters lost weight and showed signs of lung damage, but vaccinated hamsters did not. Those that received intranasal vaccination also had substantially less infectious virus in their nasal passages than unvaccinated animals.

The researchers next tested two doses of the intranasal vaccine in monkeys. Antibodies were found in the blood after the second dose, at levels resembling those seen in people who have recovered from Covid-19.

When the monkeys were then exposed to SARS-CoV-2, those that received the intranasal vaccine had less virus in their noses and lung tissue. And, 3 of 4 unvaccinated monkeys developed symptoms of pneumonia, while none of the vaccinated ones did.

More work is needed to understand the different immune response between the two routes of administration. A clinical trial is underway to test intranasal vaccination in people.—Brian Doctrow, NIH Research Matters