Monoclonal Antibody Prevents Malaria in Small Trial

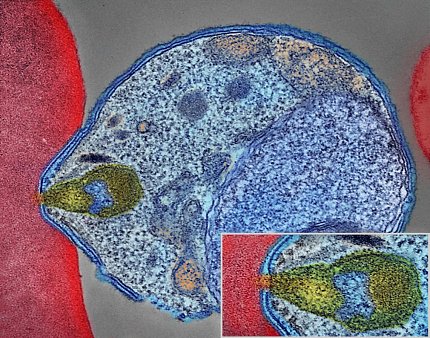

Photo: NIAID

One dose of a new monoclonal antibody discovered and developed at NIH safely prevented malaria for up to 9 months in people exposed to the malaria parasite. The small clinical trial is the first to demonstrate that a monoclonal antibody can prevent malaria in people.

Findings from the trial, conducted by scientists from the Vaccine Research Center at NIAID, were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

So far, no licensed or experimental malaria vaccine that has completed Phase 3 testing provides more than 50 percent protection from the disease over the course of a year or longer.

Malaria—a major cause of illness and death worldwide—is caused by Plasmodium parasites transmitted by the bite of an infected mosquito. The mosquito injects the parasites in a form called sporozoites that enter a person’s skin and bloodstream. P. falciparum is the Plasmodium species most likely to result in severe malaria infections which, if not promptly treated, can be fatal.

Researchers led by Dr. Robert Seder, chief of VRC’s cellular immunology section, found that a naturally occurring neutralizing antibody called CIS43 binds to a unique site on a parasite surface protein that facilitates malaria infection and is the same on all variants of P. falciparum sporozoites worldwide. The researchers subsequently modified this antibody, creating CIS43LS.

During the first half of the Phase 1 clinical trial, the study team gave half the participants one dose of CIS43LS. All participants in the second half of the trial consented to be exposed to P. falciparum in a controlled human malaria infection (CHMI), through bites of infected mosquitos in a carefully controlled setting.

Nine participants who had received CIS43LS voluntarily underwent CHMI and were closely monitored for 21 days. None of them developed malaria, but 5 of the 6 controls did. Further study indicated that 1 dose of the experimental antibody can prevent malaria for 1 to 9 months after infusion.

To build on this finding, a larger NIAID-sponsored Phase 2 clinical trial is underway in Mali during a 6-month malaria season.

“Monoclonal antibodies may represent a new approach for preventing malaria in travelers, military personnel and health care workers traveling to malaria-endemic regions,” said Seder. “Further research will determine whether monoclonal antibodies can also be used...ultimately for malaria-elimination campaigns.”