ADVANCE PLANNING IN ‘SPIRIT’

Studies Aim to Spur Dialogue on End-of-Life Wishes

It’s a tough subject to contemplate for ourselves let alone to discuss with loved ones, making it all too easy to postpone the conversation. But a series of studies suggest that preparing for end-of-life (EOL) treatment decision-making not only helps honor patients’ wishes, but also ultimately reduces the anxiety and post-bereavement distress of families.

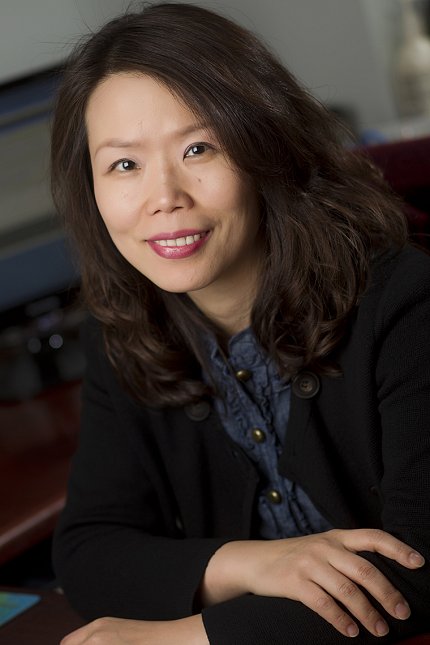

Too often, people focus on advance directives, missing an important part of the planning process, noted Dr. Mi-Kyung Song at a recent NINR Director’s Lecture.

“I think equating completing advance directives with advance care planning is the problem—the overreliance on legal documents without conducting the necessary good conversations with the patient and family,” said Song, a tenured professor and director of the Center for Nursing Excellence in Palliative Care. “Not having advance care planning that can prepare for end-of-life decision-making [can lead] to disastrous harm for the patient and lifelong distress or trauma for the family.”

Song, who also serves as the Edith Honeycutt endowed chair in nursing at Emory University, developed a protocol for patients with chronic conditions and their families that she continues to test in a series of pilot and full-scale NIH-funded clinical trials called SPIRIT (Sharing Patient’s Illness Representations to Increase Trust).

Decades of research have shown that family decision-makers—the surrogates—frequently are unaware of their loved one’s illness progression. “We often believe we have time when, in fact, we don’t,” she said.

“Surrogates lack the intimate knowledge of the patient’s wishes,” said Song. “They often do not know what’s acceptable to their loved ones when it comes to end-of-life treatment. And, [when they’re running out of time], surrogates are unprepared for decision-making during emotional turmoil.”

Think of advance care planning as a mental rehearsal for making EOL decisions, to get ready before that nerve-wracking time comes, before it’s too late, said Song.

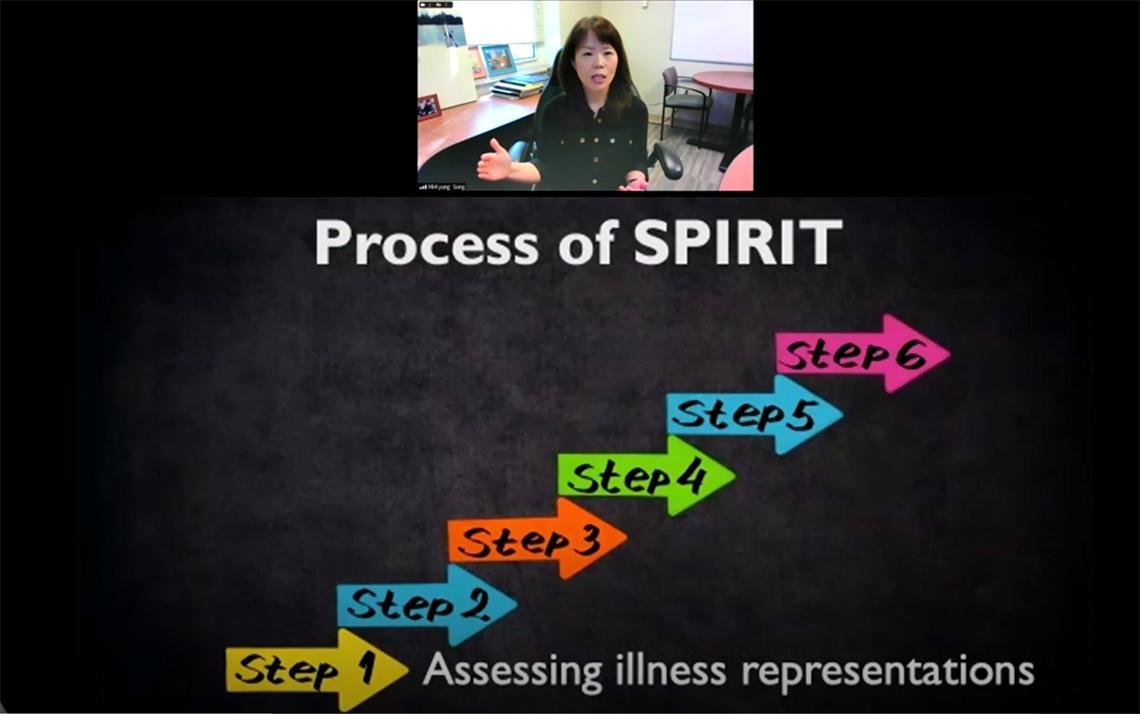

In SPIRIT, the clinician leads a guided discussion with the patient and surrogate, first asking them how the patient’s illness has affected their lives. That serves as the basis for a more detailed EOL discussion.

“A patient’s understanding or beliefs about their illness may or may not be medically correct, but it’s critically important to explore their representations first,” said Song.

Then the clinician can address gaps and concerns and, in this compassionate framework, help the patient accept and cope with new information.

The first SPIRIT trial enrolled open-heart surgery patients. The intervention helped put patients and surrogates on the same page and reduced their anxiety.

The next trial enrolled African Americans with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The syndrome, which disproportionately affects Black people, requires renal replacement therapy.

“It wasn’t so much about whether to start or undergo aggressive procedures because these patients already are living on dialysis,” said Song. “Rather, it was important to have a conversation about living on dialysis and when it would be appropriate to consider stopping [it].”

A follow-up study looked at longer-term outcomes in the same group of dialysis patients. Interestingly, most surrogates felt confident in understanding the patient’s wishes but less than a third correctly predicted them.

“Surrogates are, in general, overly optimistic about their ability to serve as a surrogate without knowing that they in fact do not know their loved one’s wishes,” Song said.

Next came a full-scale efficacy trial with ESRD patients exploring the surrogate’s post-bereavement outcome at various intervals after the patient’s death.

Those following the SPIRIT intervention showed greater agreement on goals of care at the end of life and higher surrogate decision-making confidence.

“The anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms increase shortly after the patient’s death, understandably so,” she added. “But then the intervention family member’s symptom score returned to baseline or got even lower by 3 months, while the control scores remained much higher.”

For Song, this was revealing. The results suggested “SPIRIT helps families move on with their lives instead of ruminating and wondering: ‘Did I do the right thing?’”

Song is now pilot-testing SPIRIT with dementia patients, which has unique challenges. Can dementia patients coherently articulate EOL wishes? “Is the cognitive window of opportunity still open to meaningfully participate in end-of-life discussions with family members?” asked Song.

One observation so far, she noted, is that sessions took much longer with dementia patients who kept pausing to gather their thoughts. Investigators found, though, that all patients were able to articulate EOL wishes, even those with moderate dementia. Another pilot trial is underway to explore this dynamic in dementia patients with ESRD, who must navigate choices surrounding dialysis despite cognitive impairment.

In the end, said Song, “All families who experienced less distress at the end of life had one thing in common: They knew their loved one’s wishes ahead of time.”