A Matter of place, space

Winn Urges Tackling Disparities

It’s time to address the elephant in the room: science and technology alone will not eradicate cancer.

“As we’re now entering into an era of precision medicine and immunotherapy, let’s be more deliberate in our delivery and more equitable with the distribution of this wonderful science to our communities,” said Dr. Robert Winn, director and Lipman chair in oncology, VCU Massey Cancer Center, at a recent NCI CURE Distinguished Scholars seminar.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the National Cancer Act, ambitious legislation that launched the war on cancer and established the first National Cancer Institute-Designated Cancer Centers. Winn, the second-ever African-American director of one of these centers, proposed a challenge going forward.

“We are at a crossroads now,” he said. “We need to reimagine and challenge ourselves about what the next 50 years is going to look like.”

For Winn, that means basic and translational science must go hand-in-hand with population science and health care delivery.

“I will no longer accept [the excuse] that it’s hard to address health disparities issues. Those days should be in the rearview mirror,” Winn declared.

“I recognize that even with my love of science, if we’re not paying attention to the implementation, integration and communication of that science while we’re doing some good, we may not be doing as much good as we should.”

Winn used the example of two sisters. As adults, one moves to an affluent neighborhood, the other to an impoverished area. Both sisters develop breast cancer. Will their treatments be the same? Maybe they should; perhaps they should not be.

“While biology is important to our outcomes,” he said, “I think we are missing the whole impact that place and space have on that DNA.”

If one’s surroundings lack access to fresh food and quality medical care and are riddled with environmental pollutants, place and space create more risk for disease.

Recent studies show an overall reduction in cancer deaths among Black Americans since the 1990s. “But take a better look under the hood,” cautioned Winn. “Disparities are still there.”

Breast cancer mortality continues to decrease across the country overall, but some places have much better track records than others. Improved screening is saving lives, but some parts of town lack access to this technology.

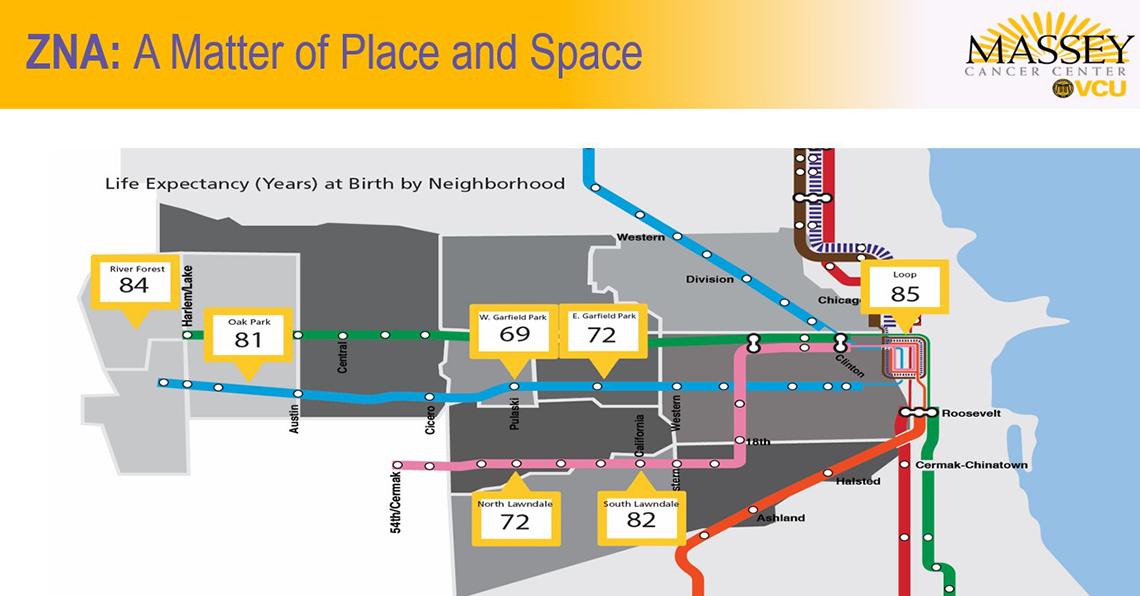

“Your zip code, your neighborhood of association—that is your ‘ZNA’—certainly intersects with and impacts your DNA,” said Winn. “And it’s that level of science I’m most intrigued by for the 21st century.”

Winn started his career as a cell biologist, studying how a dysregulated cell disrupts other cells to cause cancer. But he changed his trajectory upon learning of the stroma, the connective, supportive tissue that contributes to that spiral.

Winn made the connection that, much like the individual cell and its stroma, each person can be affected by the social determinants of health within their community.

In downtown Chicago, life is good and long. But go 4 miles west and life expectancy drops by 16 years. Go 8 miles south and it drops 30 years. Is crime to blame? Studies show violence is a negligible indicator. Other social determinants of health are at play here, created by decades of systemic inequity.

Take Richmond, home to VCU Massey Cancer Center. Back in the 1930s, despite sanctioned segregation, African-American communities such as Jackson Ward became self-sufficient and robust. But then came the urban renewal of the ’50s and ’60s that deemed these thriving areas slums and decimated them to build highways.

“Don’t tell me that structure from the past is not impacting what we live today,” Winn said. “Don’t play with me that it’s just that African Americans are indigenously more predisposed to hypertension and diabetes and cancer. Yes, biology is at play. Yes, we know with triple-negative breast cancers that ancestry is at play. But we also know the ZNA is impacting the DNA.”

One structural improvement that would yield significant benefit is investing in transportation, he suggested. Millions of Americans delay or neglect medical care because they can’t get to the doctor.

“More than half of our people are not getting to us,” said Winn. “The bench-to-bedside model [doesn’t work] if you can’t get to the bedside. Miracles can’t work if we can’t get people through the door.”

And the latest medical treatments can’t work without public trust, which is an uphill battle in communities of color. “Health science delivery sometimes gets caught up in Ivory Towers and is not getting out into the ’hoods,” said Winn. “We have to get into a habit of not [only] being in a community as long as the grant lasts, but well after the grant has finished.”

Gaining trust also requires paying close attention to how the science is communicated. “We really all need a little grace and humility as scientists,” he said. “Science must take a pause. It must listen; it must learn; and it must change.”

The CURE (Continuing Umbrella of Research Experiences) program supports individuals from underrepresented groups across the academic continuum, from middle school students through independent cancer researchers. CURE Distinguished Scholars seminars highlight innovative cancer health disparities research.