Vaccinating Against Addiction

Janda Discusses Treatments for Substance Use Disorders, Drug Overdose

Can we train the immune system to treat harmful drugs like foreign invaders? Are drug vaccines viable solutions for opioid and nicotine addictions?

Dr. Kim Janda of the Scripps Institute is working on just that. In his recent lecture, “A Vision Engaging Pharmacokinetic Strategies to Treat Substance Abuse Disorders and Overdose,” Janda discussed his work on developing heroin, fentanyl and nicotine vaccines/biologics. His research uses a pharmacokinetic (PK), treatment strategy that targets the drug molecule itself, which aims to reduce drug concentrations at the site of action thereby reducing the drug’s pharmacodynamic effects.

There are FDA-approved therapeutics for opioid use disorder, Janda shared, but frequently they leave room for improvement. Psychotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy are often insufficient on their own. Substitution therapy, such as methadone and buprenorphine (in which the illicit drugs are replaced with medically prescribed opiates), is expensive and can perpetuate dependence. And antagonist drugs such as naltrexone can have unpleasant side effects.

Vaccines may be preferable to these already existing treatments for numerous reasons: They reduce overdose risk, are inexpensive and suitable for use in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and do not require daily compliance.

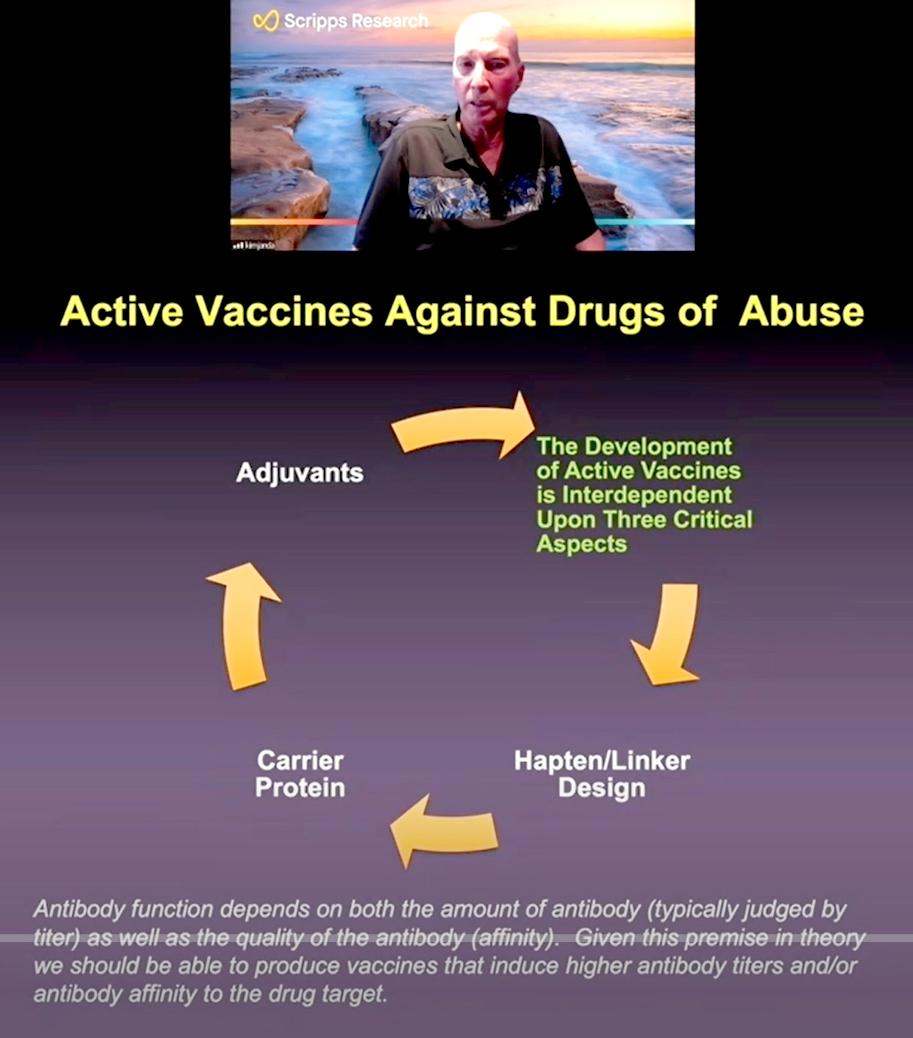

Drugs such as opioids are not naturally antigenic, meaning they do not create an immune response like a cold or flu virus (or flu vaccine) would do. Janda had to build a molecule that would stimulate an immune response against the target drug.

When creating a drug vaccine, he said, “it’s not just the amount of antibody you create, but also the quality” of those antibodies. Drugs, and opioids in particular, have high affinity for the receptors that they bind to in the body, so the antibodies that are created need to have even higher affinity to sequester the drug from its targeted receptor(s).

Janda discussed his heroin vaccine first. Heroin is a semi-synthetic opioid derived from morphine. Janda formulated vaccines that resembled heroin and morphine and tested them in the lab. His intention was to “preserve the drug-like structure as much as possible” while still allowing for the additives needed to formulate the vaccine. It was administered in animal trials and showed promise in mitigating both addiction and the physical effects of opioid use.

In one study that measured heroin self-administration in rats, formerly addicted animals that were vaccinated either ceased use altogether or maintained their level of drug tolerance. Janda also showed a video of two rats—one vaccinated and one unvaccinated—who were given heroin. The unvaccinated rat was very lethargic (“heroin sedation”) while the vaccinated rat was very active. “When these vaccines are working well, they can work extremely well,” Janda said.

Another goal was to make the vaccine stable at room temperature. After tweaking the formulation, Janda came up with a vaccine that “is stable for months at room temperature,” making it ideal for use in LMCIs that may not have the ability to refrigerate vaccines in regions that most need them.

He emphasized, though, that the vaccines still need more work. “I’m not sure how well they’re going to hold up in the clinic,” he confided. He’s looking next to explore deuteration, an isotope of hydrogen that has shown some early positive benefits over the previous version of heroin vaccines.

Janda also wanted to make a vaccine that would target fentanyl, a fully synthetic opioid that is a major contributor to rising opioid overdose deaths.

Fentanyl has a lot of different analogues, so Janda wanted to create a broadly neutralizing vaccine that could target many of these. Janda based the vaccine on 6-7 fentanyl derivatives, including ones that have been made by clandestine laboratories.

The fentanyl vaccines worked much better than the heroin vaccines.

“We were really able to keep the drug out of the brain…[and] basically control it in the blood,” Janda explained. When tested in an animal model, the vaccine fully protected against fentanyl overdose.

Janda is also exploring the possibility of a heroin-fentanyl combination vaccine, although he thinks the two original vaccines would have to be approved before the focus can shift to a “Heroin Street” shot. “The individual drug [vaccines] work better than the combo,” Janda found, “but the combo works reasonably well.”

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have become more widely known recently due to their use as Covid-19 treatments, and they also show potential as overdose treatments. Janda obtained human fentanyl mAbs by vaccinating a transgenic mouse and then going through a novel single B-cell sorting technique. These mAbs, like the opioid vaccines, sequester the drug in the blood, and could be more effective at treating overdoses than naloxone (Narcan). This was demonstrated using plethysmography as he showed head-to-head data between these two treatments with a critical dose of carfentanil. [Plethysmography measures changes in volume in different areas of the body.]

Janda was particularly impressed by the mAbs P1A4 that bound well to both fentanyl and carfentanil (an incredibly potent fentanyl analogue): “This is like the Guinness World Records with regard to antibody affinity to small molecules, so this is as good as you’re going to get here.”

Finally, he discussed his research on nicotine, which is a less dangerous drug than opioids but notoriously difficult to quit. Janda is not the first person to attempt a nicotine vaccine.

“There’ve been probably 20 nicotine vaccines that have hit clinical trials,” he shared, “and all of them have failed.”

It comes down to the chemistry of the drug, he says. Antibodies will sequester the drug in the blood, but the drug eventually must be processed. Again, this comes down to a PK/PD dilemma ideally, he thought, a better scenario would be to both sequester and degrade the drug.

Pseudomonas putida, a bacterium that lives in the soil under tobacco plants, may hold the key. It uses nicotine as its sole source of carbon and hydrogen, and avoids nicotine toxicity by degrading it with an enzyme termed NicA2.

Importantly this approach could be useful in treating pediatric nicotine toxicity (caused by ingesting liquid nicotine such as vape fluid), for which there are currently no treatments.

Janda’s research shows many exciting opportunities for treatment of substance abuse disorders. However, he is realistic about the potential for drug vaccines:

“I always tell people…I’m not selling you on ‘this will cure everybody.’ And I don’t think these vaccines will be helpful for all drugs of abuse,” Janda concluded. “I think you have to pick and choose your battles.”

The archived lecture can be viewed at https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=43773.