2001 Anthrax Attacks Revealed Need to Develop Countermeasures Against Biological Threats

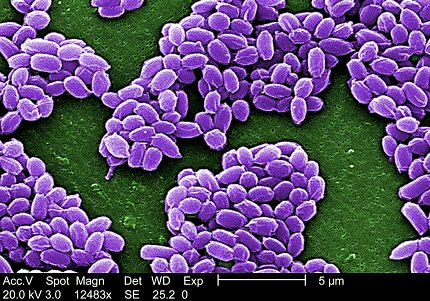

Photo: JANICE HANEY CARR

Days after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, letters laced with anthrax arrived at postal facilities, news outlets and congressional office buildings, recounted Dr. Mary Wright, during a recent CC Grand Rounds lecture.

“There were a lot of questions and unknowns about anthrax in 2001,” said Wright, a medical officer in NIAID’s Division of Clinical Research. “There just wasn’t a lot of current information.”

Anthrax is a rare, but serious infectious disease caused by gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria called Bacillus anthracis. Anthrax spores occur naturally in soil and can infect animals like cows, sheep and goats. People get anthrax by inhaling spores, eating animals that were infected with anthrax or getting spores in a cut or scrape. Inhalational anthrax is the deadliest form and without aggressive treatment, it’s almost always fatal.

“The first letters were mailed on Sept. 18, just a week after 9/11, when the nation was still in shock,” Wright said. “Senate and House offices had to close down because they received anthrax letters. There was a big outcry about the need to get diagnostic testing and figure out how to face this uncertainty.”

The attacks lasted a few months. In total, 22 people got anthrax and 5 of them died. It cost more than a billion dollars to decontaminate post offices and other government buildings. Few doctors had experience treating anthrax. Before 2001, the last case of inhalational anthrax reported in the U.S. was in 1976.

The use of mail to spread powdered anthrax spores spurred the biomedical and public health communities to develop countermeasures against anthrax and other biological threats, such as Ebola and smallpox, said Dr. Arthur Friedlander, senior scientist at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID).

“The horrendous possibility of using microbes to intentionally cause disease was realized,” said Friedlander. “We were now focused on providing medical countermeasures.”

Because inhalational anthrax infections are almost always lethal and occur infrequently, human challenge studies are not ethical or feasible, he said. In response to the attacks, FDA issued the Animal Rule in 2002. It allows “for the approval of drugs and licensure of biological products when human efficacy studies are not ethical and field trials to study the effectiveness of drugs or biological products are not feasible.”

Anthrax spores do not germinate all at once, Friedlander said. They can remain dormant for a long time inside a host. Because antibiotics destroy only germinated spores and bacteria, discontinuing post-exposure treatment before every spore germinates can have deadly consequences.

In a 1993 non-human primate study, Friedlander and his colleagues found prolonged antibiotics alone could result in significant long-term protection.

“These results suggested that therapy for an unimmunized person exposed to an aerosol of anthrax spores should consist of long-term suppressive antibiotics,” he said.

The study became the basis for CDC’s recommendation that people who have been exposed to anthrax take antibiotics for at least 60 days. After the attacks, about 10,000 people potentially exposed to anthrax were put on antibiotics for 60 days. However, only 44 percent adhered to the treatment regimen.

Friedlander; Dr. Nicholas Vietri, an infectious disease physician formerly with USAMRIID and now at VA Boise Healthcare System; and Wright entered an interagency collaboration to perform a series of studies. First, they sought to determine if receiving an anthrax vaccine after exposure could reduce the time non-human primates were required to be on antibiotics. The results suggested that, when combined with post-exposure vaccination, antibiotics can be given for as few as 14 days in this model. Once again, CDC updated its treatment guidelines based on Friedlander’s research to include vaccination after anthrax exposure; current guidelines advise that antibiotics be continued for 2 weeks after the last dose of the vaccine series.

“Shortening the duration of antibiotic post-exposure prophylaxis in a bioterrorism event involving B. anthracis by adding post-exposure vaccination would be of great benefit because of non-compliance and side effects associated with prolonged therapy,” Friedlander noted.

For treatment of active infection, antibiotics may be given for as little as 10 days in non-human primates, Vietri explained.

In this study, monkeys were exposed to a high dose of anthrax and given antibiotics for 10 days beginning after anthrax bacteria were found in the bloodstream. The animals that survived once the antibiotics ended were immune to reinfection, which correlated with the development of antibodies to the protective antigen (PA) of anthrax.

The group concluded that, “Patients who are treated for symptomatic anthrax and recover should be tested for the development of an immune response to B. anthracis,” he said. “The presence of anti-PA antibodies may be useful in determining when antibiotics may be discontinued.”

Researchers have made progress against anthrax, Wright said. Still, clinical questions remain. For example, can non-invasive imaging findings characterize the stages of infection? How many antibiotics are needed to treat an infection? When is the best time to administer anti-toxin treatment and what are the long-term effects in survivors of anthrax?

“The anthrax letter attacks of 2001 revealed the urgent need to be able to understand old pathogens using current modern medical tools,” concluded Wright. “The investment in biodefense and emerging infections research infrastructure—and in mechanisms such as the Animal Rule—have made rapid discovery possible years later.”