Ode to Joy

Young SCA Patient Is Pain-Free Following Transplant

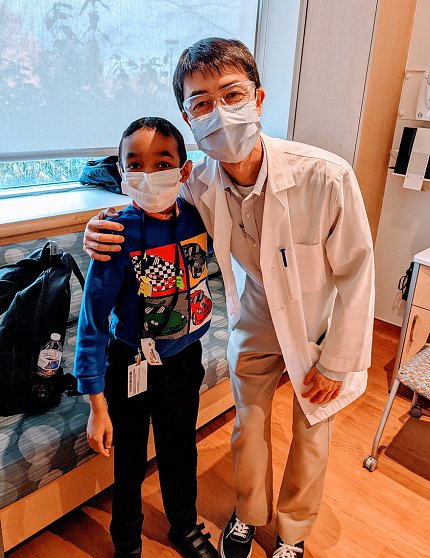

Photo: Lucas Sant

“It’s such a blessing,” exclaimed Dr. Lucas Sant as he and his son Caesar walked into the Children’s Inn on a brisk, mid-March day. The two had just come from the Clinical Center where Caesar had his 6-month checkup.

Two days earlier, an unseasonable snowstorm made its way down to Memphis, where the family lives, and Caesar played in the snow for the first time. The 30-minute joyful outing was unimaginable before his treatment, when staying out in the cold would’ve been too painful because sickle cell anemia compromised his circulation.

At the checkup, “Caesar looked well and said he feels pretty strong,” said NHLBI staff clinician Dr. Matthew Hsieh, who performed Caesar’s bone marrow transplant in September. “He’s not quite up to wrestling his siblings yet, but I think he’s getting there.”

It’s a story of science fusing with other healing elements—a loving family, music and a big dose of faith.

As a toddler, Caesar began playing violin. By age 4, he was playing concertos, studying multiple languages and excelling in karate. But then, over an 18-month period, Caesar had three strokes. The third stroke, in June 2014, left him in critical condition, unable to speak or walk.

When he came home from the hospital, Caesar began intensive physical therapy. Lucas, a neuroscientist and behavior educator, put his career on hold to devote himself full-time to his son’s care.

In sickle cell disease, a gene mutation causes hemoglobin—the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells—to clump and become crescent-shaped. The blood cells often get stuck traveling through small blood vessels, which is chronically painful. The disease deprives the body of oxygen and can cause life-threatening conditions, including stroke.

The best chance of a cure is a bone marrow transplant from a healthy, fully matched relative. But Caesar’s younger sister Maria-Anita, then 2, was not an exact match and carried the sickle cell gene.

At the time of Caesar’s paralyzing stroke, his mother Aline was 3 months pregnant. The family wanted another child and chose to try in-vitro fertilization (IVF) to enable the potential for a life-changing treatment for Caesar. One embryo was an exact match and free of sickle cell.

When his sister Helen was born, Caesar had begun walking again and was slowly relearning to play violin. The family saved the baby’s umbilical cord for a future transplant.

In early 2021, Lucas connected with NHLBI senior investigator Dr. John Tisdale and enrolled Caesar, age 13, in an NIH matched sibling sickle cell trial. In September, Caesar arrived at the Clinical Center for the transplant, where he received bone marrow from Helen, then 6 years old.

The NIH team wound up not using Helen’s stored cord blood because they could get more blood stem cells from her bone marrow. The transplant doctor described the procedure.

“Imagine the bone marrow is like a parking garage,” explained Hsieh. “It’s a physical structure that houses cells, or cars, that move in and out of the garage.

“Before transplant, all of Caesar’s cars and the guards to the garage are all his own. For us to do the transplant, we must make some space in the garage. We take away some guards—or, lower the immune system—so we can get his sister’s cells, or cars, into the garage.”

To do this, Caesar underwent 3 weeks of radiation and chemotherapy and received antibody medicine prior to transplant. His “parking garage” is now filled with two sets of cars and guards—a blend of his and his sister’s blood cells and immune systems, what’s known as mixed chimerism.

“We’re hoping that further down the road, 6 to 12 months from now, he will have a stable mix of cars and guards in the garage that tolerate each other,” said Hsieh.

Even well-matched bone marrow transplants carry significant risk, but fortunately so far Caesar has not experienced transplant-related complications.

At his 6-month checkup at NIH, Caesar had an echocardiogram, breathing test and blood draws that were all clear, and said he’s been pain-free since the transplant. Hsieh said he hopes to see Caesar’s red blood cells continue to increase.

Back at the Children’s Inn for one night, Caesar smiled. He was soft-spoken and walked with a limp. A week earlier, he had fallen while playing with a friend. “The legs will take time,” due to effects from his previous serious stroke, said Lucas. Caesar continues working hard in physical therapy; it may take another year for his legs to gain full strength.

The other day, Caesar sat, looking deep in thought and his dad asked what was wrong. Nothing was wrong.

“I was just thinking,” said Caesar, “how I’m about to be normal like my sisters.”