High-Tech Imaging Reveals Details About Rare Eye Disorder

Photo: NEI

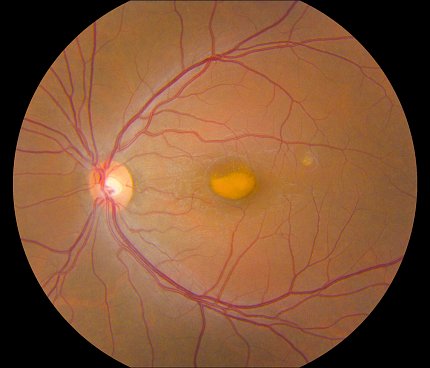

Using a new imaging technique, NEI researchers have determined that retinal lesions from vitelliform macular dystrophy (VMD) vary by gene mutation. Addressing these differences may be key in designing effective treatments for this and other rare diseases.

VMD is an inherited genetic disease that causes progressive vision loss through degeneration of the light-sensing retina. Genes implicated in VMD include BEST1, PRPH2, IMPG1 and IMPG2. Depending on the gene and mutation, age of onset and severity vary widely. All forms of the disease have in common a lesion in the central retina (macula) that looks like an egg yolk and is a build-up of toxic fatty material called lipofuscin.

VMD affects about 1 in 5,500 Americans and there is currently no treatment for this condition.

Dr. Johnny Tam, head of the NEI clinical and translational imaging unit, used multimodal imaging to evaluate the retinas of patients with VMD at the Clinical Center. Tam’s multimodal imaging uses adaptive optics—a technique that employs deformable mirrors to improve resolution—to view live cells in the retina, including the light-sensing photoreceptors, retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells and blood vessels in unprecedented detail.

Tam and his team collaborated with clinicians at the NEI Eye Clinic to characterize 11 participants using genetic testing and other clinical assessments, and then evaluated their retinas using multimodal imaging. Assessment of cell densities (photoreceptors and RPE cells) near VMD lesions revealed differences in cell density according to the various mutations. Tam is using multimodal imaging on other retinal diseases, including age-related macular degeneration.