Customs Amid Crises

Historian Explores India’s Cultural Responses in Pandemic Times

Photo: Anten Jesu

People in different parts of the world often view the same global event in different ways. A population’s unique outlook stems from a distinct national history and shared experiences as a people. In India, responses to past pandemics have been shaped by common beliefs, practices and traditions and sometimes even superstition.

Dr. John Mathew, associate professor of the history of science at Krea University in India, along with postgraduate students Ishita Pradeep, Karthika Satyanarayan, Lipi Savita and Rutuja Rokade, have been mining the National Library of Medicine’s archives, among other sources, to uncover how Indian culture has informed the experience of pandemics from cholera, plague and influenza to Covid-19.

Articles, memoirs and archival records from NLM’s collections help tell the history of cholera in India—one of the first meticulously recorded pandemics in the country—which began in 1817 and had successive waves until 1920. Rooted in unsanitary conditions that tainted tap water, “cholera provoked tremendous fear in the local populace,” said Mathew. Symptoms ranged from mild to severe.

“Infectious diseases were widespread in villages, particularly in untouchable dwellings. Cholera was one such disease,” said Mathew. “Each house had at least a couple of deaths due to cholera and people were afraid of touching the dead body of a person who had died of the disease. Only the inhabitants of the house could carry the dead body for cremation.”

An estimated 8 million people died in India from cholera from 1817 to 1920.

“What is staggering is the number of deaths across the 19th and early 20th centuries [from] a disease where India was seen as the source,” he said. “Cholera touched a considerable number of places in the world through much of the 19th century and, in some ways, foreshadowed what would come through other diseases.”

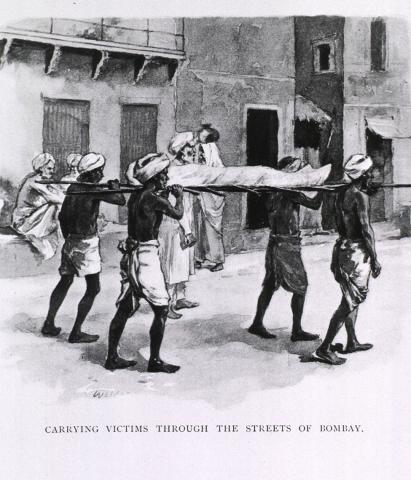

Photo: NLM History of Medicine

In the 1890s, a bubonic plague epidemic hit the city of Bombay, part of a global pandemic that began in China in 1894. Over the following several decades, the plague killed 12 million people in India and millions more worldwide.

In response, the British colonial government came down with a heavy hand. Concerned about the impact on trade, officials ratified the Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897, which authorized health officials to confiscate or destroy property, enforced quarantines for suspected plague victims and instituted systematic inspection and detention of travelers by land and sea.

The Epidemic Diseases Act was again invoked during Covid-19. “Some laws have long shadows,” noted Mathew.

The plague had embittered the population against the colonial government. Mathew said, “The already embattled populace in the wake of previous and competing diseases, including cholera and malaria—and in the context of a more global cataclysm [the first World War]—had developed its own sense of entitlement to yet another disruptive force.”

Before India had recovered from the plague, an even more destructive pandemic swept through the country from 1918 to 1919. Influenza—which arrived largely from soldiers returning after World War I—killed 20 million people in India alone.

“Suddenly, [that figure] made sense when Covid hit, which really brings to the fore what the sense of staggering loss was at that point in time,” noted Mathew.

Photo: Sandhya Kumari/Gallerist.in

And yet, while the plague caused panic and riots, public response to the flu was much different.

“Even as daily mortalities [exceeded] the normal rate of death at a proportion of 18 to 1 on occasion—figures that have become frighteningly familiar in our recent crisis—the ravages of influenza and the waning days of the Great War [prompted] a fairly muted societal response,” he said.

Mathew attributed the muted response in part to growing public apathy in the postwar period. The flu hit hard and swiftly, whereas the plague lingered for many years.

Local attitudes about pandemics in India were rooted in religion. Some outbreaks evoked deities, such as Sitala, goddess of smallpox.

“Many of the deities preceded the European colonial movement,” Mathew added, “even if some were exapted [had a different function from its original] to pandemic purposes during [colonial times].”

Photo: NLM History of Medicine

Sitala’s counterpart in southern India, Mariamman, was associated with cholera as well as chicken pox and plague. More recently, since smallpox was eradicated, Sitala has been worshiped for another disease.

“The spread of HIV/AIDS was perceived as a form of spirit possession, and belief in Sitala is seen as protective of the disease,” said Mathew.

In the late 19th century, Dr. Edgar Thurston, superintendent of the Madras Museum, wrote a book about omens and superstitions in India, from animal superstition and snake worship to the evil eye. One such story involved a ceremony that occurred in Travancore when disease prevailed. The people drew an image of the goddess Bhadrakali on the ground in five colors, sang songs and role-played a fictitious murder of the demon Darika, waving a torch to ward off the evil eye.

Mathew concluded with a personal reflection. To help put superstition and culture related to disease and death in context, he recalled an encounter he once had in Virginia—where he was studying for his doctorate in ecological sciences. Upon hearing Mathew was from India, the man he was chatting with said, ‘That’s where they worship rats, right?’”

While offended at the time, Mathew said such an account is part of the national heritage, but should not stand alone, “much like the picking up of venomous snakes in parts of Appalachia in a particular religious context does not define the culture of the whole United States.” Collecting many diverse narratives can provide better context and perspective on public health crises.

“As we wrestle with issues of rationality and ideology, magic and science, nationalism and devotion and always history,” he concluded, “we could do worse than to call to mind the insight of Nigerian-American author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie…who [spoke] about the danger of the single story. As we reflect upon cultural practice, may we remember that.”