History Office Shares Images of Black Pioneers at NIH

Photo: OFFICE OF NIH HISTORY AND STETTEN MUSEUM

For February, the Office of NIH History (ONHM) is highlighting important firsts of Black scientists and administrators across NIH history.

A 1963 group photo (above) of the National Heart Institute’s (now National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute) Laboratory of Biochemistry features two Black women trailblazers, Mary G. Burroughs (front row, r) and Juanita P. Cooke (front, second from l).

Cooke, who joined NIH in 1952 as a chemist, was named as a contributor to the studies of protein folding that earned Dr. Christian Anfinsen the Nobel Prize in chemistry. While continuing her work in the lab, Cooke became the first NIH employee to receive an Equal Opportunity Achievement Award from the Department of Health and Human Services.

Photo: OFFICE OF NIH HISTORY AND STETTEN MUSEUM

Alma LeVant Hayden was passionate about chemistry. She earned her master’s degree in chemistry at Howard University before joining the National Institute of Arthritic and Metabolic Diseases (now National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases) in 1951. She became well versed in cutting-edge chemical analysis, like paper chromatography, a technique she demonstrated in the photo. She also became a nationally recognized expert in spectrophotometry. In 1956, she left NIH for FDA where she eventually headed its Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry’s Spectrophotometry Branch. At the time of her hiring, she was likely the first Black scientist at FDA.

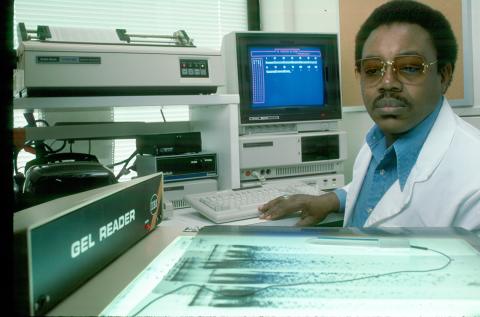

Photo: OFFICE OF NIH HISTORY AND STETTEN MUSEUM

Dr. William Coleman Jr. excelled at research and administration during his 40 years at NIH. While a scientist at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, he studied Helicobacter pylori (a bacterium that causes stomach infections), using technology like the DNA gel reader seen in this photo. He would later become NIH’s first Black scientific director when he took the position at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities in 2011.

Photo: OFFICE OF NIH HISTORY AND STETTEN MUSEUM

Alongside those whose names and stories are known, there are many unidentified individuals whose roles at NIH are memorialized in documentary photos on other topics.

At right, in an image from the ONHM photograph collection, an unidentified technician in the early 1980s from the National Cancer Institute Laboratory of Pathology loads a histomatic tissue processor, a machine that could test hundreds of samples simultaneously for many different cancer pathologies.—Devon Valera